Britons are the most willing to take a COVID-19 vaccine of any country

With the government recently coming in ahead of its target to offer vaccines to all of its priority groups by mid-April, the programme now aims to offer all British adults their first dose of the vaccine by the end of July.

Many countries are still grappling with ‘vaccine hesitancy’ – people being unsure about or unwilling to take a COVID-19 vaccine. This is not the case in Britain, with only 11% being vaccine hesitant in our latest survey. This is the lowest figure in all of the countries YouGov surveys on this matter. Only 6% of Britons currently say they will refuse to take the vaccine, with another 5% unsure.

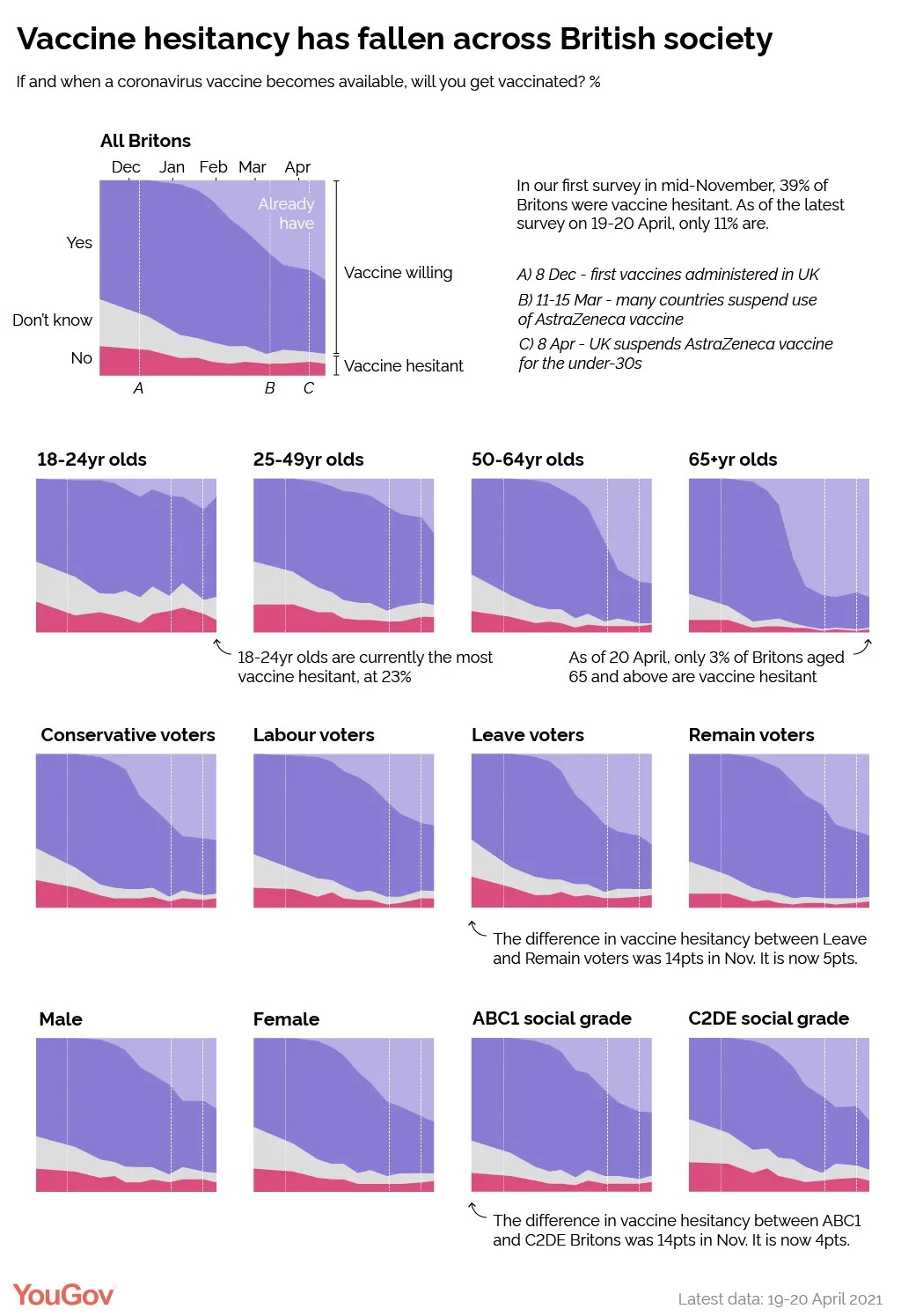

Vaccine hesitancy has declined significantly across UK society since YouGov first started asking the public in mid-November – back then 39% of Britons were vaccine hesitant, with 24% unsure about taking the vaccine, and another 15% said they would refuse to do so.

The large majority of Britons in all social groups are willing to take the vaccine

Not only is vaccine hesitancy down in British society overall, it has fallen substantially within every demographic group YouGov looks at.

Currently, the most vaccine hesitant group are 18-24 year olds, at 23% – 8% say they won’t take the vaccine, and 15% are unsure. By comparison, 18% of 25-49 year olds are vaccine hesitant, falling to 6% of 50-64 year olds and 3% of those aged 65 and above.

Nevertheless, this does represent a 23pt reduction in vaccine hesitancy among 18-24 year olds since November, and a 28pt drop among 25-49 year olds.

It is also worth noting that these groups are the least likely to have been offered the vaccine yet – just 12% of 18-24 year olds and 36% 25-49 year olds say that they have already had a jab. It is likely, however, that once the vaccine programme reaches these age groups we will see some more of the vaccine hesitant convert to vaccine willing.

The differences between other social groups are much smaller, where they exist at all. Men and women have equally low levels of vaccine hesitancy, at 12% apiece. Back in November women had been slightly more likely to be vaccine hesitant than men (42% vs 36%)

Britons in the ABC1 social demographic group – generally synonymous with middle class occupations – have a vaccine hesitancy rate of 10%, compared to 14% of those in the C2DE group – generally aligned to working class occupations. At the onset of our study, the gap was much wider – 47% of C2DE Britons had been vaccine hesitant, compared to 33% of ABC1 Britons. This 33pt drop among the C2DE group is the largest of any demographic group.

Conservative and Labour voters are similarly likely to be vaccine hesitant, at 9% and 11% respectively. Remain voters are only slightly less likely to be hesitant than Leave voters (7% vs 12%). While rates of Conservative and Labour vaccine hesitancy have always been similarly close, the gap between Leave and Remain voters was much wider back in November, at 44% to 30% respectively.

AstraZeneca travails and vaccine hesitancy

It is not clear if the blood clot issues surrounding the AstraZeneca vaccine had an effect on vaccine hesitancy. On 9 March, prior to the media agenda becoming dominated by concerns about the vaccine, hesitancy levels were at 11%. In the next survey, on 21 March, they stood at 13%. Among 18-24 year olds, this change was from 24% to 30%. This could indicate that a fraction of the public became more concerned, or it could just be statistical noise, as the difference in both cases is within the margin of error.

It is also possible, given that the AstraZeneca concern was at its peak from 11-15 March, that vaccine hesitancy levels rose but had fallen again by the time of our survey. A separate survey asking about the safety of the various vaccines, conducted much closer to the time on 15-18 March, did show a small fall in the perceived safety of the AstraZeneca vaccine, but this effect did not spill over to the other vaccines we asked about.

Even if vaccine hesitancy did rise, it is clear that concerns disappeared almost as swiftly as they arrived. What is more of a problem than those who are temporarily concerned by reports in the media will be the hard core of people who remain unwilling to take the vaccine.

With the level of vaccine hesitancy having remained consistent these last few weeks, it could be that this survey question is beginning to uncover exactly who this group is – although as stated above, the picture will not become completely clear until the vaccine programme reaches the very youngest groups. When that happens, we will start to see how many of the young vaccine willing are prepared to follow through on their confidence and get their shot, and how many of the vaccine hesitant forget their fears once an inoculation is offered.