A YouGov study looks at how far Britons believe people have control over characteristics like their weight, addiction and intelligence, and how the way we judge one another is affected by this

How much control do we have over ourselves? It is a simple question, but one with far-reaching implications.

For instance, the level of control you believe someone has over various aspects of their life would likely impact not just how you might personally judge, say, a drug addict, but also your attitudes to whether and how much the state should be willing to help them.

Studies have indicated, for instance, that many aspects of weight gain and addiction are down to genetics, and that being poor makes making good financial decisions harder. Even our political views may be less under our control than we realise.

That being the case, YouGov has explored how far Britons believe people can control various personal characteristics, how much they judge people for having those characteristics, and the interaction between those two sets of views.

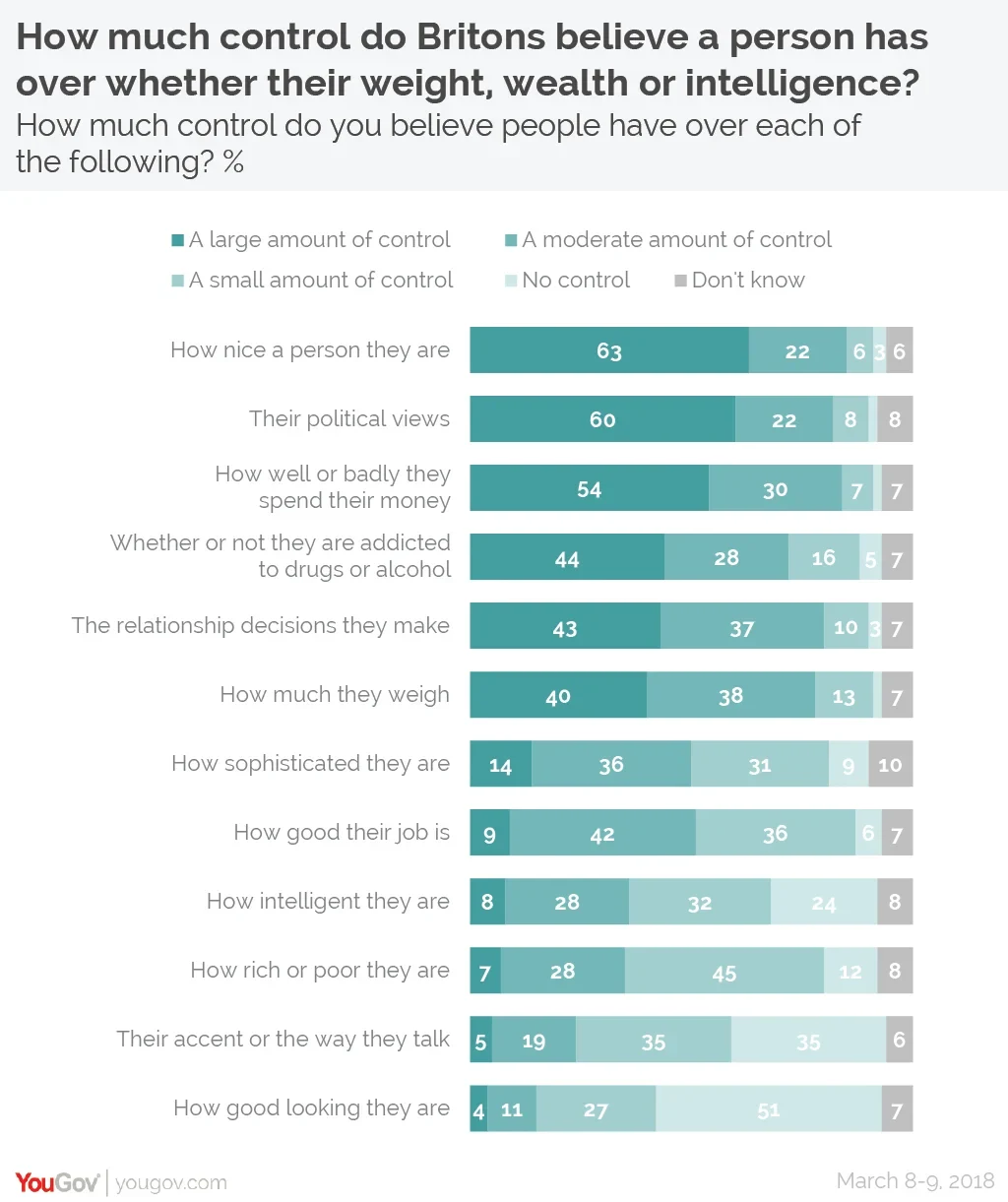

What can we control about ourselves?

Of the 12 characteristics we asked about, Britons believe the one we have most control over is how nice a person we are. More than six in ten (63%) of Brits say they believe a person has “a large amount of control” over this. A further 60% believe we have a large amount of control over our political views, while 54% feel the same about how well or badly we spend our money.

An additional 44% believe people have a large amount of control over whether or not they are addicted to drugs or alcohol, and 40% think people have a large amount of control over how much they weigh.

Much further down the scale only 8% of Britons believe people have a high level of control over their intelligence, and just 7% feel people have a large amount of control over how rich or poor they are.

At the very bottom of the scale, the characteristic we believe people have the least control over is how good looking they are – only 4% say someone has a large amount of control over this, while half (51%) say a person has “no control” over this.

Perceptions of control affect how readily people judge others, but changing these perceptions might not help in all cases

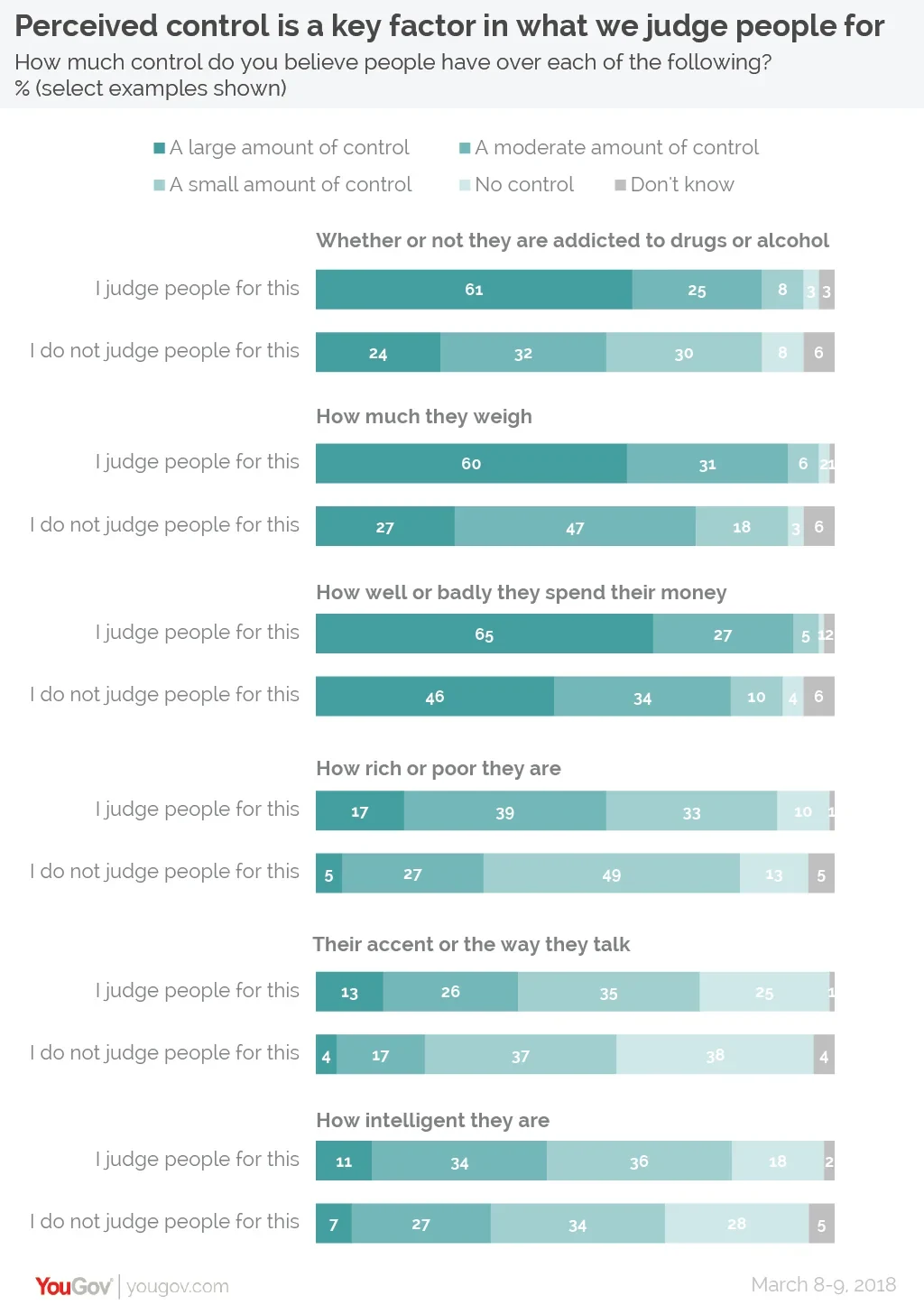

Unsurprisingly, for most of the attributes there is a strong correlation between control and judgement. The more control people believe a person has over a personal attribute, the more likely they are to say they judge people on that attribute (and the more likely they are to say it is acceptable to judge someone on that attribute).

So for instance, while 61% of people who judge a person for being a drug addict believe people have a large amount of control over addiction, this figure is only 24% among those who say they do not judge people for being addicted to drugs.

This means that politicians and campaigners looking to change attitudes on issues like treatments for addiction and obesity would do well to start a public discussion about the extent to which people really have control over and these aspects of themselves.

However, such an approach might not work across the board.

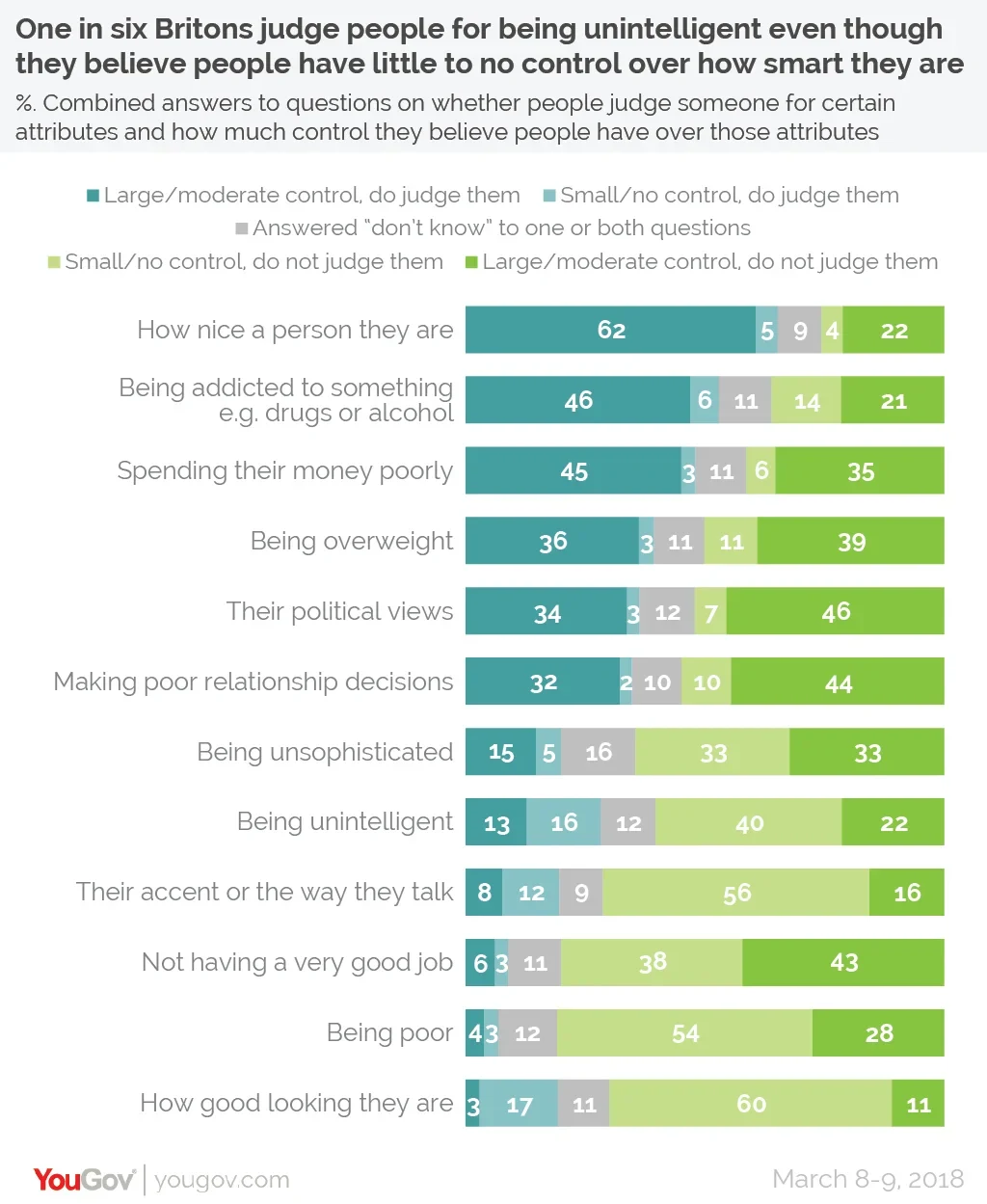

If we look at the attitudes of people who judge someone over a given characteristic, in most cases the vast majority feel that a person has a high or moderate level of control over that attribute. But in the case of three attributes – accent, looks or being unintelligent – more people who judge someone for this think people have a small level or no control over this attribute than think they have a moderate or large level of control.

In other words, the majority of people who judge a person for their accent, looks or for being unintelligent do so in spite of the fact they believe a person has little to no control over that aspect of themselves.

With regards to looks and intelligence this amounts to one in six Brits (17% and 16% respectively), and one in eight for accents (12%).

With evidence showing not only that accents affect the way we perceive others but that they can limit our professional opportunities, people hoping to tackle bias against people for their accents – as well as looks and intelligence – will need to find alternative means of convincing Britons to treat their fellow countrymen fairly.

Photo: Getty