Driverless cars may be the transport of the future, but consumers are not yet positive about embracing them

Driverless cars are on their way. Driverless taxis are currently being trialled in Singapore, Uber will shortly be launching a trial of driverless cars in Pittsburgh, and in the UK trials have been approved in Greenwich, Bristol, Milton Keynes and Coventry.

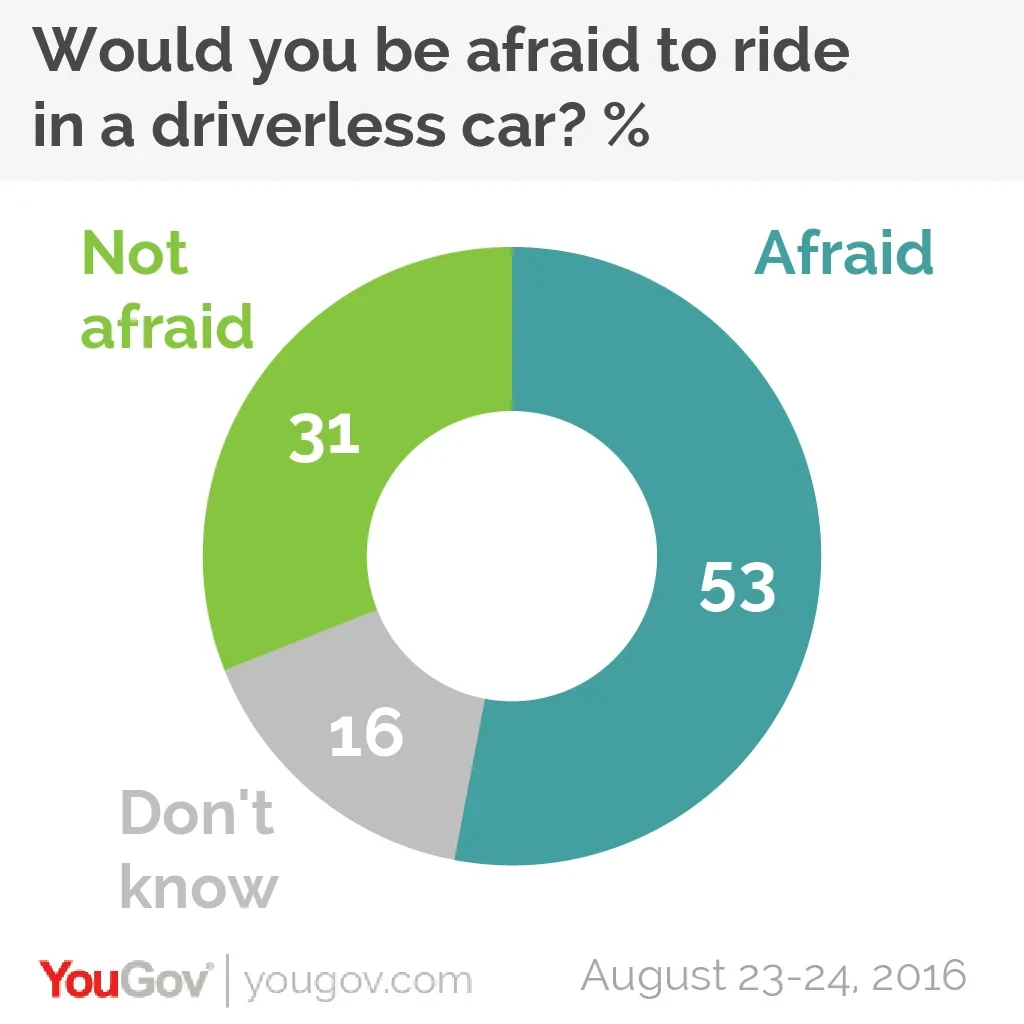

This is not a welcome prospect for the majority of Britons. A new survey by YouGov finds that 53% of people would be afraid to ride in a car that drives by itself, whilst just 31% would not be afraid. Women and less affluent people are the most likely to be afraid to ride in a driverless car. Overall, just 28% of people feel positively about introducing driverless cars to the UK, compared to 38% who feel negatively about the prospect.

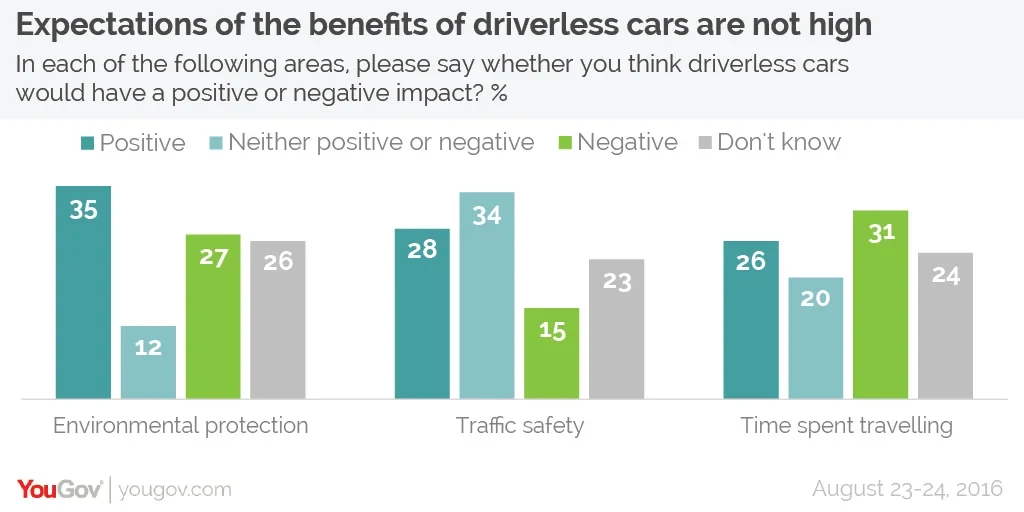

The public is also heavily divided on the possible benefits of driverless cars. Barely a third of people believe that driverless cars will be good for the environment, only 28% think they will improve traffic safety and just 26% think they will reduce the amount of time spent travelling.

One key area of difference is between car drivers and non-drivers. In all areas non-drivers are more likely to be positive about driverless cars than car drivers and less likely to be negative – for instance, non-drivers are nine points less likely to be afraid of riding in a driverless car than car drivers (47% vs 56%). One possible reason for the split could be because non-drivers are already accustomed to giving control of their journeys over to someone else, or simply that car drivers don't think a computer could do a better job than them.

A thought experiment on the moral considerations of driverless cars is currently being run by MIT. Called the “moral machine” experiment, it envisages a situation where a driverless car has lost control, and asks you to decide whose lives to prioritise in a series of scenarios.

The moral consideration the experiment highlights is: if a computer is driving a car, how should that car be programmed to act if a fatal accident is about to happen? Whose life should the car try hardest to save? And who should be responsible for drawing up those sets of priorities for driverless cars?

The British public are unprepared for such considerations. Should a fatal accident be occurring, 24% think the car should prioritise the life of its occupants, whilst 19% think it should prioritise the lives of pedestrians. More than half, however, say that they don’t know (54%).

Again, when it comes to who should be the ones to decide the moral rules around driverless cars, people are undecided. A third (32%) think that the rules should be decided by a panel of experts, whilst 15% think the public should have their say in a referendum. Just 3% of people trust politicians to legislate on the matter. The largest section of people, however, say that they just don’t know (39%).

Photo: PA