For a party whose aim is not to dismantle capitalism but to improve it, making a commitment to full railway nationalisation could have worsened Labour's business credentials

A battle is underway inside the Labour Party, and polls are providing some of the ammunition. But like bombs, bullets and bayonets, polls need to be deployed with care.

Last week Ed Miliband said that if he becomes Prime minister, parts of Britain’s rail network might return to public ownership. Each time a franchise reached the end if its life, the state could compete against the private sector for the new franchise.

However, over the weekend, 50 local Labour parties, two regions and the rail unions were reported to be campaigning for a different policy. They want the state to take over all rail franchises when they expire. The issue will come to a head at the party’s National Policy Forum at the end of next week. Neal Lawson, chair of Compass, a left-of-centre pressure group, told The Observer: ‘Just giving the state the right to bid is a fudge that won’t work, will cost hundreds of millions of pounds and was rejected in the 2010 Labour manifesto. The party and the public want rail in the public’s hands.’

Others can debate the intrinsic merits of different ways to own the railways. This blog’s concern is the state of public opinion. And Lawson is right about what voters say they want. A YouGov survey last November for the Centre for Labour and Social Studies found that two in three voters (including just over a half of all Conservative supporters) want both the railways and energy companies taken away from the private sector and nationalised.

Yet this does not mean Labour can be sure of gaining votes by promising to return the railways to public ownership. Here’s why.

Whenever a party or its leader announces a policy, it is likely to provoke a response on two levels. The first is obvious: voters will decide whether or not they like the policy. Railway nationalisation passes that test. The doubts concern the second level of voter reactions. Each major policy is judged not just in isolation, but on what it says about the party’s character.

That is where Labour could be vulnerable should it campaign for all of Britain’s railways to be removed over time from the private sector. We need not strain our powers of prediction to imagine how the Conservatives and much of the media would react. They would say that Miliband is taking party back to the Left and the bad old days of inefficiency, trade union power and frequent strikes, that he doesn’t like or understand business, and that Britain would slide from prosperity to penury.

None of this need worry Labour if its aim were to open a big ideological gap with the Conservatives. It could then say: yes, we do think capitalism stinks, and we would like to reverse the changes that Margaret Thatcher inflicted on Britain three decades ago; yes, we do think our country would be fairer, more contented and better run if the trade unions had a far bigger say in our nation’s affairs. If that were Labour’s pitch, voters would have a clear choice at next year’s general election – just as in 1983, when Labour last set out a firmly left-wing prospectus. I suspect the result would be roughly the same.

However, that is plainly not Miliband’s position. He presents himself as pro-business. He wants to support the better bits of the private sector and raise the standards of the bits behaving badly.

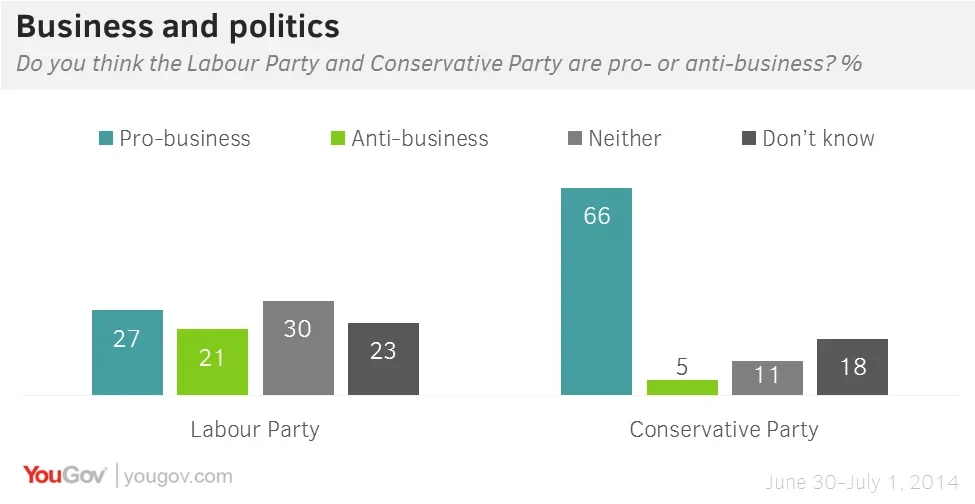

The issue, then, is whether a plan to take over the whole of Britain’s railway network will enhance Labour’s reputation for knowing how to make capitalism work better. I doubt that it would. Last week, YouGov asked people whether they thought Labour and the Conservatives were pro- or anti-business. This is what we found:

A traditional socialist would be untroubled by those figures. If anything, she would be concerned that as many as 27% regard Labour as pro-business. But for a party whose aim is not to dismantle capitalism but to improve it, these are worrying results. And I reckon a commitment to railway nationalisation would make them worse.

To repeat: I am not arguing whether renationalisation is intrinsically a good or bad idea. It might be an excellent proposal, leading to cheaper, more reliable trains. Were the Conservatives to promise it, they might win public approval. But that’s because few people think the Tories are out to do down big business. The policy would not damage their brand in the way it would probably damage Labour’s.

As long as Labour wants to make capitalism work better, the party and its leader need to tread with great care on such issues as the railways. Miliband’s challenge and opportunity are to set out policies that enhance his reputation for knowing how to harness the dynamism of the market to the wider purpose of prosperity and social justice. His cause would be set back if he were to say, explicitly or implicitly, that the private sector is wholly incapable of running the railways and the state could be guaranteed to run them better. Fairly or unfairly, such a message would drown out all his attempts to show he can work with the private sector.

On the other hand, his policy of allowing the state to compete with private companies supports his argument that decisions should respect the best bid, whether from the state or the private sector. That is why the current battle inside the Labour Party matters so much. It is not just about how to run Britain’s railways but whether Labour’s attitude to capitalism should be rooted in pragmatism or ideology. Miliband’s approach could end up with the state running all of Britain’s railways – but because this turned out to be the right decision, franchise by franchise, not because he wants Labour to shift significantly to the left.

To their credit, true left-wingers accept this analysis. They know they are engaged in a struggle to revive socialism. Those who support that struggle are plainly right to argue for the railways to be renationalised, even if the short-term cost is five more years of opposition. But those who want Labour to win next year should hope that Miliband defeats his critics.

Image: Getty