Miliband has yet to persuade the electorate that he has the personal qualities needed to lead Britain. Fresh research helps to explain his failure – and suggest what he must do to revive his fortunes

He is strong. He understands voters’ problems. He knows how the economy ticks, and how to make it tick faster. He would fight for Britain’s interests and stand firm in a crisis. He keeps his promises.

‘He’ is the ideal candidate for Prime Minister. Sadly for Ed Miliband, few voters think he fits the bill.

Almost four years into his leadership of the Labour Party, and with just ten months to go to next year’s election, Miliband has yet to persuade the electorate that he has the personal qualities needed to lead Britain. YouGov’s regular tracker questions show how his attempts to win voters over have failed. Fresh research for Prospect and the Sunday Times helps to explain his failure – and suggest what he must do to revive his fortunes.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

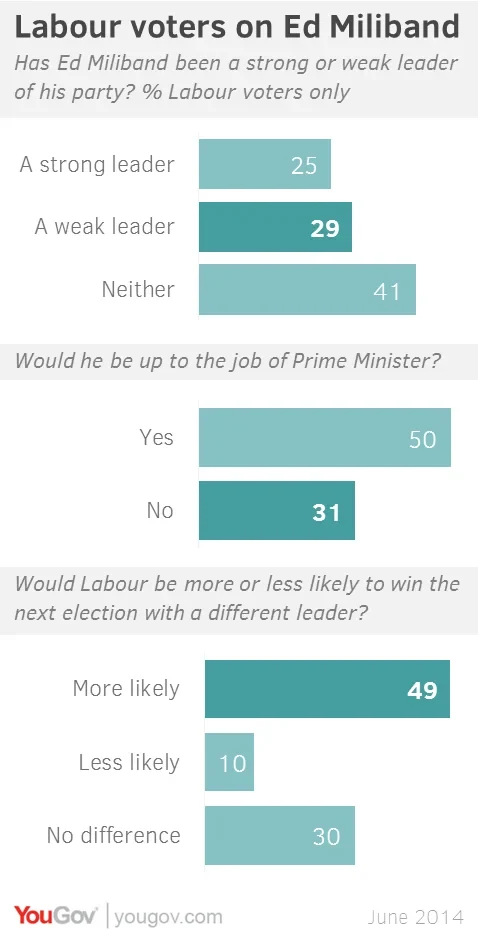

To some extent the story is a familiar one, of Miliband suffering low personal ratings. This disappointment in his leadership now extends to Labour’s own supporters:

- More Labour voters regard him as weak than strong

- One in three don’t think he is up to the job of Prime Minister

- Half of them think Labour would do better with a different leader

Of course, a vote is a vote: one cast reluctantly counts the same as one cast by the most fervent enthusiast. If Labour can hold on to the 37-38% it has been scoring in recent YouGov polls, Miliband will enter Downing Street next May. His problem is that Labour can’t afford to lose any of its current support. It is a short step from disappointment to disillusion, and then from disillusion to defection – especially when he faces a Government that can trumpet the benefits of a growing economy, a shrinking deficit and falling unemployment.

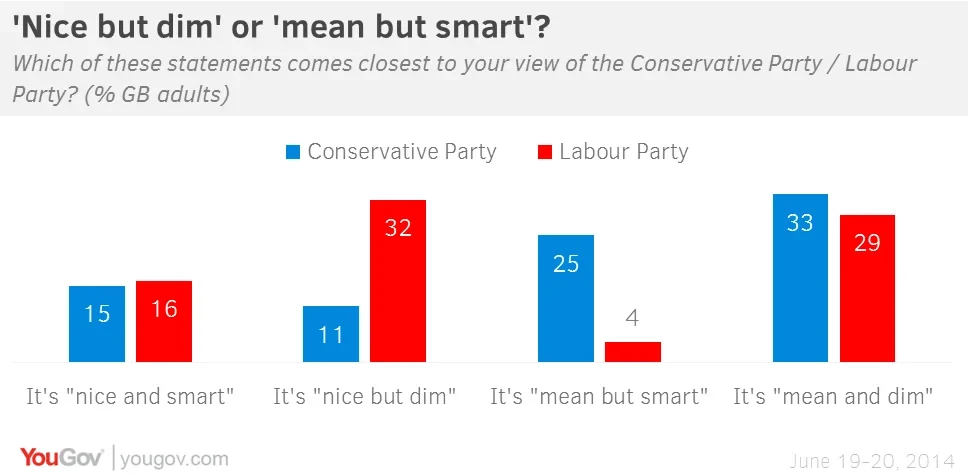

For Miliband to shore up Labour’s fragile lead, he has to win voters’ hearts, and also their heads. At present he is ahead on the former – but behind on the latter. This emerges from a question that draws shamelessly on Harry Enfield’s comic creation, Tim Nice But Dim.

We asked people how they thought of Labour and the Conservatives. The responses are telling. 37% say Labour is “nice but dim”, against 11% for the Tories. On the other hand, 25% reckon the Conservatives are “mean but smart”, against just 4% for Labour. With both parties, outright hostility is far more common than full support, with twice as many saying “mean and dim” than “nice and smart”.

Overall, 48% say Labour is nice, against 26% for the Tories. But 40% think the Tories are smart, while only 20% credit Labour with this virtue.

Did Labour choose the wrong brother, as many people argue? We tested this by repeating the best Prime Minister question, but substituting David for Ed. The result is startling. David Miliband scores 35%, 12 points more than Ed, while Cameron tumbles ten points to 23%.

So, would a David Miliband-led Labour party be heading for victory next year, rather than the close contest that seems likely? Very possibly, but we can’t be sure. Voters’ judgements about Ed are based on his performance; their views about David are based on a hypothesis. Had he won back in 2010, he would have had to grapple with many of the same problems as Ed: reviving Labour’s reputation for economic competence, navigating the tricky politics of recession and recovery, and holding together a Labour Party that has historically been fractious after losing power. We can’t be certain how well he would have done. (It’s worth remembering that David, a committed advocate of New Labour, might have provoked more internal divisions than Ed).

The real point is that this finding indicates how disappointed many voters are in Ed’s performance. Millions remain unconvinced by the coalition’s record and would like to back a Labour leader, but don’t think Ed is a match for Cameron.

Why not? We can rule out one theory, which the Conservatives have advanced from time to time: that “Red Ed” is too left-wing for the electorate. If anything, voters – including many Conservatives – are often keener than Miliband on left-wing measures, such as nationalising the railways, curbing bankers’ pay and blocking foreign take-overs of British companies.

Miliband’s problem is more personal. By more than four-to-one, voters regard him weak rather than strong; by three to one they say he is simply not up to the job of Prime Minister. On both measures, Cameron scores more positive than negative responses. A third comparison of the two men is arguably even more troubling. We asked people whether they thought the Prime Minister and opposition leader were “in touch or out of touch with the concerns of people like you”. This is where one might expect Miliband to do well and Cameron baldy. That’s half right: only 20% think the Prime Minister is in touch. But Miliband’s figure is only slightly higher: 25%. Tory attacks on Miliband’s ideology have failed; but his opponents in politics and the media have struck home with comments that his family, upbringing, education and career have been far removed from the experiences of normal folk.

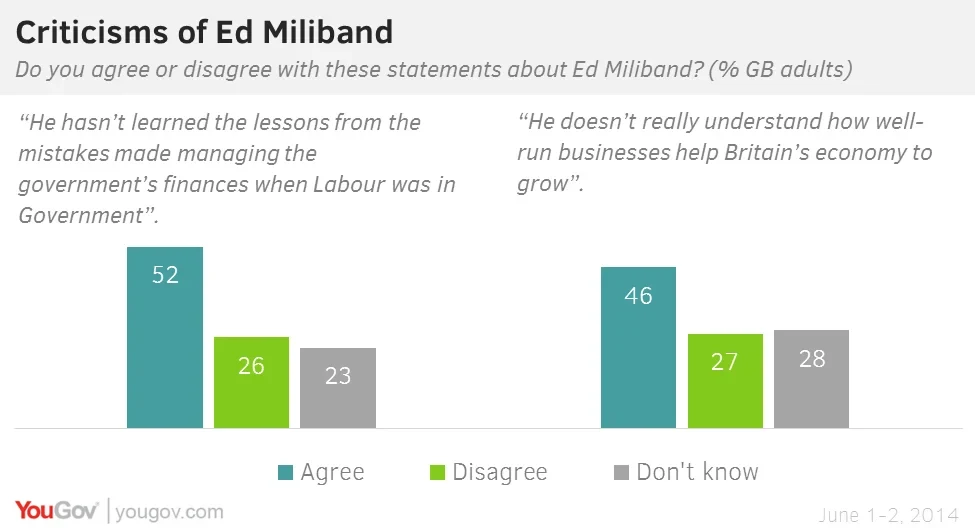

These perceived personal deficiencies are enhanced by a real political drawback – not ideological fervour but economic competence. We tested two criticisms that are often levelled at him:

These are bad figures, though they do contain one glimmer of hope. Many people have yet to make up their mind on these points. This is because millions of voters pay close attention to politics only at election time. In principle, Miliband will have the chance over the next ten months to win over such people – though, of course, the Conservatives will be trying equally hard to persuade them that Labour’s leader cannot be trusted with the nation’s economy and finances.

For the moment, the Tories remain ahead. We have repeated a question we first asked three years ago, shortly after Ed Balls succeeded Alan Johnson as Labour’s shadow chancellor. Who do we trust more to run Britain’s economy, David Cameron and George Osborne, or Ed Miliband and Ed Balls? The Conservative pair outscore the Labour pair 36-25%, with 39% don’t know. These are the lowest figures we have recorded for Miliband and Balls – and the highest number of “don’t knows”. Again, there is a chance over the next 10 months to coax uncertain voters off the fence, albeit after three years of making no progress. On the other hand, the Tories will be able to trumpet continuing recovery to protect their lead.

If Miliband can neutralise the Tories’ advantage on the economy, then he may be able to shift another indicator that is causing him problems. From time to time over the past ten years we ask people to imagine that the opposition came to power and its leader became Prime Minister. Would they be delighted, dismayed or not mind?

We have always found that far more people say dismayed than delighted, whether they were asked about Michael Howard, Cameron or Miliband. Just 18% would be delighted by a Miliband victory. Even if we count “wouldn’t mind” as a cautiously positive view, then we find that Labour today is still in negative territory (44% dismayed, 41% delighted or wouldn’t mind). This contrasts with the Conservatives shortly before the 2010 general election (positive 48%, negatives 41%) and the 2005 election (positives and negatives both 44%). Even Labour voters have only limited enthusiasm, with just over half, 57% saying they would be delighted. Plainly, Miliband must both fire the passions of Labour supporters, and address the fears of those people who would benefit from a change of government but are not currently inclined to vote for one.

One big reason for this lack of enthusiasm is a widespread fear that a Miliband government would fail to solve Britain’s big problems. On only one does he come out ahead – and then only just: 40% think his administration would boost home-building, while 38% think it would not. On everything else we tested, fewer than one-third think it would succeed. They include his pledge to keep gas and electricity prices as low as possible. Even more alarmingly, his worst scores relate to the three issues of greatest concern to millions of voters: strengthening the Government’s finances (23% say he would succeed, 54% fail), making the economy grow faster (22%-55%) and reducing the number of immigrants arriving in Britain each year (15%-64%).

So is defeat inevitable? Not yet. One reason is that victory needs fewer votes than in the past. In the Fifties, the target was almost 50% of the popular vote. By the Eighties it was 40%. In 2005, Labour won outright with 36%. It is just possible that Miliband could become Prime Minister at the head of a Labour-Lib Dem coalition government with only one in three voters backing Labour and twice as many supporting other parties. However, this depends on enough Lib Dem MPs holding their seats where the Tories cam second last time – and Ukip hanging on to enough former Conservative voters to tilt Con-Lab marginals Labour’s way.

If Labour is to win a real mandate, rather than crawl past the winning post by default, it must tackle its, and its leader’s, weaknesses. In addition to the normal policy and campaigning challenges that face any opposition, here are four tasks that cannot wait.

1. Blunt the Tory attack that the last Labour government caused the recession. It’s too late to persuade voters that Gordon Brown was blameless; but Miliband can still argue that leading politicians and bankers around the world (including the Conservatives) misjudged the risks prior to 2008. His opportunity is to say that the world has changed, everyone has lessons to learn, and Labour has learned them. As our poll shows, too few of us believe that. This leads to…

2. Show that he knows how to harness the dynamism of capitalism to the benefit of all. Miliband has made forays into specific topics, such as energy prices, banks and, more recently, the housing market. Voters have yet to see him join the dots together to provide a bigger picture. “Milibandism” has nothing like the clarity of “Thatcherism”. Nor has he said enough about how Labour would help, rather than merely regulate, businesses to grow. Every Labour pronouncement on business should answer this question: if a young British equivalent of Bill Gates or Steve Jobs were starting out today, how would Labour help them to succeed? This ambition needs Miliband to…

3. Secure third-party endorsements for each new policy. Privately, some energy company executives support Miliband’s plans to reform their market, just as there are decent bankers and landlords who would welcome new rules for financial services and rented homes. But if any of them have said so publicly, their remarks have gone unnoticed. Voters need to be convinced that Miliband’s plans really will work, and they are unlikely to take his word for it that they will. He needs relevant business leaders, and not just trade unionists, academics and friendly journalists, who will tell us: “yes, this makes sense”.

4. Start sounding like a Prime Minister in waiting rather than a perpetually angry critic of the coalition. His attacks on Cameron are often well-argued and sometimes witty – but almost always counter-productive. Despite having been a Cabinet minister, he gives too many voters the impression that he is a rookie debater, not a potential national leader. Unfair? Possibly. But politics is seldom fair. In 1997 Tony Blair (who had never been any kind of minister) showed that youthful vigour and public respect can go together. Miliband may wish to distance himself from some of Blair’s later decisions, but he needs to find ways to emulate Blair’s early appeal.

This blog draws on commentaries for the latest issue of the Sunday Times and the July issue of Prospect

See the original Prospect article