It won’t happen, but the message from YouGov’s latest poll for Prospect is clear: the Church of England should abandon religion and become a political party.

Back in 1957, Gallup asked people a range of questions about their faith. They found that most of us were Christians who regarded Jesus Christ as the Son of God. We also drew a clear distinction between religion and politics. We wanted religious leaders to worry about our souls, but not about government policy.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

Half a century later, we have repeated Gallup’s questions and discovered a precipitous decline in religious belief. The decline in Church attendance reflects more than a stay-at-home culture dominated by television and, now, computer technology. It flows from a collapse of faith in the central tenets of Christianity.

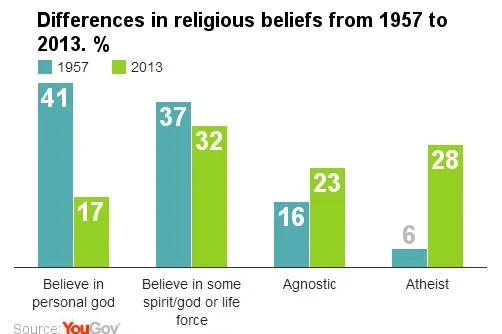

Back in the Fifties, fully 78% thought either there was a personal God (41%) or ‘some sort of spirit, God or life force’ (37%). Just 22% were either atheists (6%) or agnostics (16%). Today there are almost exactly the number of religious as non-religious Britons. And atheists now easily outnumber believers in a personal God.

There has been an even sharper collapse in the belief that Jesus Christ was the son of God: down from 71 to 27%. And the decline looks set to continue. Whereas 35% of people over sixty hold this belief, the figure among people under 25 is only 9%.

Large numbers of doubters can even be found among people who declare a religious allegiance. One third of the public count themselves as part of the Church of England or Scotland; only 45% of them say that Jesus was the son of God. The figure is higher among Catholics, at 67% - but this still means that one Catholic in three does NOT share this belief. (Too few respondents to our survey belong to other Christian groups to analyse with confidence.)

As in 1957, we are more likely to believe in life after death than in the devil, but both figures are much lower. Here, as in much of the poll, there is a marked gender gap. Women are more likely to believe there is life after death (39%) than not (26%). Men divide in the opposite direction; by 41-27% they reckon that when we die, that’s the end of us.

One issue that was little discussed in the Fifties but is more controversial today – especially in the United States, but also in Britain whenever Creationists wish to set up new schools – is evolution. A clear majority of us think Darwin was right, and life has evolved through natural selection over billions of years. Church of England adherents divided similarly to the population as a whole, but Catholics don’t: just 39% of them accept Darwinian evolution, while slightly more, 44%, either think the Bible tells the real truth (16%) or believe in intelligent design (28%).

Given all these findings, it’s not surprising that only 19% of the public reckon religion can answer all our most of today’s problems, compared with 46% in 1957 – while the proportion saying religion is ‘largely old-fashioned and out-of-date’ has doubled from 27% to 58%. Even among Anglicans and Catholics, belief that religion has the answers is a minority view.

Nor should we be amazed that, by almost-two-to-one, we would like to separate Church and State – an issue on which people were evenly divided in the Fifties. And the really bad news for the Archbishop of Canterbury is that there is only modest enthusiasm for the link among C of E adherents, with 46% favouring it, 36% opposed and 18% undecided.

All of which makes our final finding all the more striking. In 1957 most people thought church leaders should keep out of politics. Today, slightly more of us think people like Justin Welby should be free to “express their views on day-to-day social and political questions” than think they should keep their views to themselves.

In short, we have more respect for what the Archbishop says about greed and poverty than what he says about faith and theology. Perhaps he should consider spending Easter not in a cathedral but a political conference, pondering resolutions and not the resurrection.

This commentary appears in the January 2014 issue of Prospect

Image: Getty

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here