We may be undergoing a revolution in the politics of gender - since 2010, women have shifted towards Labour more than men

Not all revolutions happen suddenly. Some are slow but remorseless. One of these may be under way. It concerns the politics of gender. Historically women have been slightly more Conservative than men, while men have tended to veer more towards Labour. The gap, though never huge, used to be sufficiently pronounced to have meant that male-only electorates would probably have returned Labour to power at every election from 1945 to 1974.

For the past two decades, the voting patterns of men and women have been similar. Labour’s landslide victory in 1997 was propelled, in part, by enthusiasm for Labour by women under 40, offsetting the Tories’ continuing hold on the loyalties of women over 60.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

Since 2010, women have shifted towards Labour more than men. If we combine all the polls we conducted in November, we generate a total sample of more than 37,000. This provides robust data from different sub-groups. Last month we found that Labour enjoyed an eight point lead over the Conservatives among women (40%-32%), compared with a five point lead among men (38%-33%). The gender differences aren’t large, but they are consistent: the contrast between men and women was much the same in September and October.

What is happening? Two things stand out from our data. The move to Labour has been especially marked among women under 30, and also among public sector workers. (Public sector workers have turned against the Government regardless of gender; but women outnumber men in the public sector, while men form a majority of private sector employees.)

It looks, then, as if the Conservatives in particular are paying a price among women just now for holding down public sector pay and for acquiring the reputation of being dominated by older, better-off men.

If so, these are specific problems that, in principle, the Tories could remedy in years to come. But I suspect an additional, more profound, factor may be at work. Its effect may be small year by year, but likely to be large over time.

Earlier this year I argued that gender similarities are more common than gender differences. Broadly speaking, men and women worry about much the same things and want similar things done – on taxes, immigration, crime and so on. But occasionally clear differences do emerge. For example, men have been far keener than women on military action in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria.

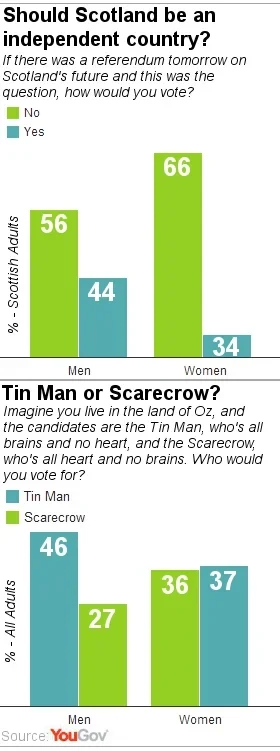

In recent weeks, YouGov has detected clear gender gaps in two particular surveys for The Times. First, last week’s survey on Scotland’s coming referendum found a 12 point ‘no’ lead among men (56-44%), but a mammoth 32-point ‘no’ lead among women (66-34%). If the overall referendum ends up closer than it looks today, it may well be that most men will take the plunge and vote ‘yes’, while most women, fearful that an independent Scotland might not be able to afford its current levels of social protection, will plump for the less risky option and vote ‘no’.

So: women are more risk-averse when it comes to specific decisions on war-and-peace and, in Scotland, major constitutional change. Does this flow from something more fundamental about the attitudes of some men and some women to the world around them?

Our second survey throws some light on this. We asked people across Britain a question that was first posed in the United States around 15 years ago. We invited people to imagine they lived in the land of Oz, and the candidates for power were ‘the tin man, who’s all brains and no heart, and the scarecrow, who’s all heart and no brains. Who would you vote for?’

Men plumped for the tin man by a large, 46-27% margin, while women divided evenly, 36-37%. Conservative voters also preferred the Tin Man, by 60-21%, while Labour voters preferred the scarecrow by 41-32%. Relatively speaking, then, when people are forced to choose, Tories and men tilt towards brains, while Labour voters and women tilt towards heart.

On these figures, perhaps the key question about voting habits is not why Labour now seems to be gaining the upper hand among women, but why the gender gap is so small.

In the United States the gulf is much wider. Exit polls at last year’s presidential election found that men divided 52-45% in favoured Mitt Romney while women backed Barack Obama by 55-44%. The heart-brain divide looks clear-cut. As usual, the people who put heart first backed the Democrats – the party traditionally associated with social protection. I’m not sure that it’s right to call the Republicans the party with brains: their electoral strategy has been pretty stupid in recent times. But they are the party associated with small-government, anti-welfare, free-market measures and to that extent could be regarded as the tin man party appealing to tin man voters.

Why do we not have the same gulf in Britain? Partly, because the Conservative Party has never been as ideologically doctrinaire as the Republicans now are; and David Cameron has been trying to project the Tories as the party that wants to protect the public services despite the spending cuts.

However, I wonder if the main reason is that Labour is not just the pro-welfare party-of-the-heart, but also the party with its roots in the male-dominated world of the trade unions. In the past, its reputation as a party for the male working class more than offset its reputation as the caring party.

If so, then what may be now happening is that the ‘male’ part of Labour’s brand has weakened over the past two decades, and now counts for slightly less than the ‘female’ part of Labour’s brand. This could explain Labour’s clear lead among women under 30: they belong to a generation for whom trade unions are either irrelevant or, if they work in the public sector, less male-dominated.

If this is right, then the gender gap is likely to widen in the years ahead, with women becoming relatively more Labour and men relatively more Conservatives.

That, though, is a long-term projection, to be re-examined in, say, 2030. More immediately, the task facing both parties is to convince voters that they are neither tin man nor scarecrow. The Conservatives must persuade more voters that they really do have a heart and not just the minds of tough-minded bean counters, while Labour must show that it has a brain and not just a sentimental desire to make life better for the majority.

Image: Getty

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

See the Scottish Referendum poll results