For the third time in two years, opponents of British membership of the European Union have lost their lead when people are asked how they would vote in a referendum.

YouGov’s latest poll, conducted last week, shows ‘in’ and ‘out’ tied at 39% each. It may be a sampling fluke: when we next ask the question the lead may be restored. But, below the surface, Britain’s mood does seem to be shifting.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

Here are two reasons why. The first is that two previous blips were driven by specific events: in December 2011, when David Cameron had a bust up with the other EU member states over the euro zone; and in January this year, when he delivered his much-publicised speech about his plans for a referendum. Our figures recorded short-term public reactions; within weeks, as the news agenda moved on, support for membership fell back.

This time, there has been no specific event to move figures – and therefore no particular reason, beyond sampling fluctuation, why the shift should be reversed.

Secondly, our latest findings reflect a gradual shift in underlying sentiment. Last year, we conducted 12 surveys in which we asked people whether they would vote to leave or stay in the EU. The gap between the two sides never dropped below 10 points; on average, 48% said they wanted to leave the EU while 32% said they wanted to stay in.

The pattern this year has been different. Leaving aside the blip in opinion around the time of the Prime Minister’s January speech, most of our surveys since February – and all since mid-August – have reported leads of less than 10 points. Much of the shift has taken place among Conservative supporters. Most of them still want to leave the EU, but not by such massive margins as a few months ago.

What, then, is going on? Since the beginning of this year, we have regularly asked people about the consequences of leaving the EU. The results have shown no clear trend. Voters are evenly divided on the economy, jobs and prosperity; few think Britain’s influence in the world would increase if we left the EU. There is certainly nothing in these figures to explain the narrowing of the gap since the summer.

Moreover, in one respect, we might expect opposition to the EU to be hardening around now. We have found repeatedly that a huge source of resentment towards the EU is Britain’s inability to keep out immigrants from other member states. The final, transitional, curbs on people settling here from Romania and Bulgaria end in January. This prospect has prompted many news stories and much debate in recent weeks.

Our latest poll for the Sunday Times shows how much Britons dislike this state of affairs. 72% say the rules on immigration from countries inside the EU are not tight enough and should be strengthened. Only 31% of us accept the argument put forward by some economists and business leaders that immigration in recent years has been good for Britain’s prosperity; 57% think our economy, and not just social harmony, has suffered.

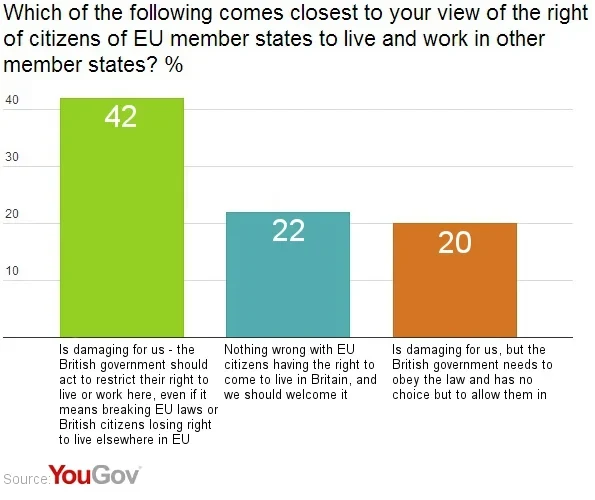

However, when we asked people what should be done about immigration from the EU, something curious happens. We gave people three options – support continued free movement because there is nothing wrong with it; put up with it because we need to obey EU laws even though we don’t like it; restrict the right of EU citizens to settle in Britain, even if this means breaking EU laws.

By far the biggest group, 42%, want us to break EU laws and change the rules. 22% are happy with the present system, while 20% think we should put up with them even though we don’t like them. So, while the present system is disliked by three-to-one, voters are evenly divided (42% each) on whether Britain should defy the EU or not.

I think these findings provide a clue to the gradual shift in attitudes to EU membership. It has nothing to do with positive enthusiasm for the EU. This remains in short supply. A generation ago, memories of the Second World War and its aftermath fuelled a widespread sense that European unity was the path to lasting peace and prosperity. These days, we take peace for granted; and the upheavals in the Eurozone have damaged public faith (and not just in Britain) in the EU’s ability to deliver prosperity. The big-picture idealism of pro-Europeans in the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies has gone.

Today, the question that the referendum debate implicitly poses is, not ‘do we love the EU?’ but ‘should we put up with it?’ I suspect the public mood has shifted not because the positive case for British membership has gained in appeal, but because, as the prospect grows of a referendum in the not-to-distant future, the dangers of departure loom larger in people’s minds. It’s not that more people than before think departure would, say, be bad for jobs, but that this issue influences voters more than it did when a referendum was a more distant prospect. The prose of economic calculation is beginning to count for more than the poetry of sovereign pride.

As a result, more of us think we must put up with the EU, despite its faults, rather than take the risks of leaving the club. Indeed, this is roughly the signal that Cameron and William Hague have been sending, as they make clearer than they have in the past that they want Britain to stay in the EU.

If this analysis is right, then both sides have clear challenges. Opponents of the EU need to persuade people that (for example) the Confederation of British Industry is wrong, and that leaving the EU would actually be good for jobs and investment. Supporters of the EU need to persuade voters that there is a positive case for the benefits of membership, not merely a negative case for grudging acceptance that it is the less dangerous of two unattractive options.