Women are less likely than men to ask for promotions or pay rises and are more likely to cite factors such as lack of confidence or gender as barriers

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, released earlier this year, sparked a flurry of discussion in the UK, US and elsewhere about the challenges women face in the modern workplace. In the book Sandberg argues that women often lack the self-confidence of men and don’t negotiate as often or as aggressively for professional advancement. She also gives women advice on how to ask for a pay rise, something that reportedly made immediate impact.

New YouGov research, conducted for the Sunday Times, provides evidence that there is still a way to go for British women, who lag behind their male counterparts in asking for pay rises and promotions.

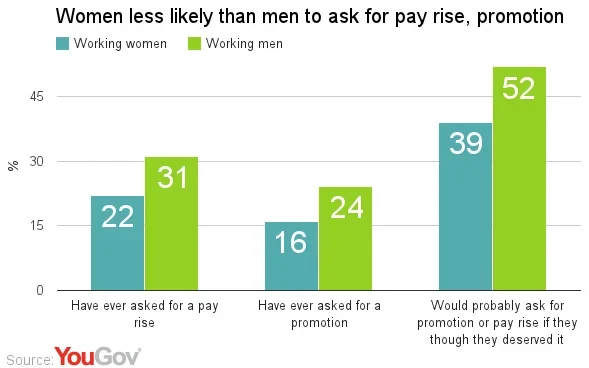

Women who work full or part time are less likely than working men to have ever asked for a raise or promotion, by a margin of 9% for pay rises and 8% for promotions, and a minority of women (39%) say they would probably ask for a promotion or pay rise if they thought they deserved it, compared to a majority (52%) of men who say they would.

Of the men and women who have asked for a pay rise, women also tend to be somewhat less successful. Women reported being successful around 60% of the time, compared to a male success rate of about 80%. When asking for promotion, reported success rates are the same (50% for both men and women).

And despite their relative difficulty climbing the ladder, women are no more or less likely than men to think they are capable of doing the job of people senior to them at work, something which one third (34%) of both men and women say they are capable of.

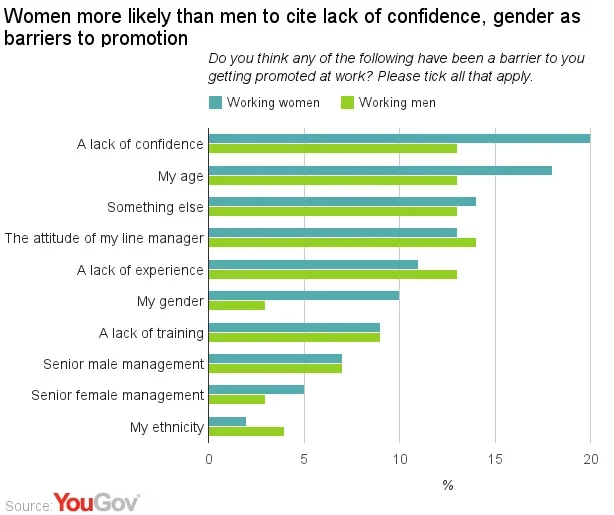

The research also suggests that lack of confidence is a key factor in discouraging women from seeking promotions. One in five women said this had been a barrier to professional advancement, twice as many as cite gender.

Although gender, along with lack of confidence and age, is a factor cited by significantly more women then men.

The findings appear to lend support to a theory backed by Sandberg, that while it’s socially acceptable for men to be assertive and aggressive, women are held to a different standard.

Sandberg says, ‘Little girls get called 'bossy' all the time, a word that's almost never used for boys.’

And indeed, even as women do not seek promotion or pay rises as often as men, over a fifth (22%) of men see women in the workplace as ‘too pushy’ – compared to only 13% of men who say other men at work are ‘too pushy.’ Women judge men and women as too pushy in just about equal measures, however.

That many of Sandberg’s arguments appear to borne out in the experiences of real working women may explain part of why her book has been so influential.

And though its long term impact remains to be seen, the book has already been a success in many respects: as of this fall Sandberg’s book has already sold 1 million copies, been on top of bestseller lists since it’s launch in March, and even been credited for ‘ignit[ing] an international movement that made feminism mainstream again.’

Image: Getty