Faith symbols welcome at work, but not the burka

First a recap: In 2006, Nadia Eweida was sent home from work by her employer, British Airways (BA), for breaching uniform code after she refused to remove a chain necklace with a Christian cross.

This became a 7-year journey: BA soon changed its uniform policy to include certain displays of faith, but refused to pay Ms Eweida for time missed from work during the episode. She then sued her employer on grounds of religious discrimination, eventually taking her case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg, after UK courts and employment tribunals upheld BA’s original decision.

Now finally in January this year, the UK Government was overruled by the ECHR and ordered to pay €32,000 in combined damages and costs to Ms Eweida. The judgement also decreed that BA had violated her legitimate right to religious expression, as the small silver cross was deemed too discreet by the Court to have damaged the company’s corporate image.

YouGov research on British attitudes to the ECHR in recent years has tended to show significant public scepticism towards the value of Britain’s commitment to the Court and its rulings.

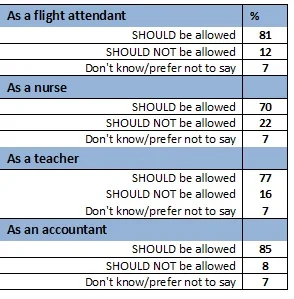

But in the case of Ms Eweida’s crucifix, at least, British public opinion and the ECHR largely agree. In a recent YouGov survey of British adults, 81% of respondents said it should be allowed to wear a chain necklace with a Christian cross while working as a flight attendant, versus only 12% who said it should not be allowed and 7% who selected “Don’t know/prefer not to say”.

This is not to say, however, that a majority of Britons consistently support the same principle of religious expression in the workplace.

In late January, YouGov conducted a multi-sample study of British attitudes to wearing religious items at work as part of an on-going collaboration with Dr. June Edmunds of Cambridge/Sussex Universities on the politics of human rights in Europe.

Results show overwhelming public support for the freedom to wear items like a small crucifix or kippah in the workplace, but not for the burka. In the latter’s case, support for the principle of faith-symbols at work is seemingly trumped by opposition and uncertainty towards the garment itself, even in a work environment with no hands-on physical or public facing responsibilities.

Strong support for the crucifix at work – even as a nurse

In the first of three nationally representative surveys, we focused on the crucifix, asking respondents if they thought it should be allowed to wear one while working in four different scenarios: as a flight attendant; as a nurse; as a teacher; and as an accountant.

We then followed the same process for two other samples, with the second survey asking if it should be allowed to wear a burka or Muslim body cloak, and the third asking if it should be allowed to wear a kippah, or Jewish skullcap, while working in these same four roles.

Looking at the first sample on attitudes to wearing the crucifix at work, we asked specifically:

“Thinking about wearing religious clothing or symbols at work, do you think people in the UK SHOULD or SHOULD NOT be allowed to wear a chain necklace with a Christian cross while working in the following roles?

<1> As a flight attendant?

<2> As a nurse?

<3> As a teacher?

<4> As an accountant?”

Results show strong support for being allowed to wear a crucifix in all four roles:

Notably these results also include a large majority supporting the right to wear a small cross while working as a nurse, which this time puts British public opinion at odds with ECHR rulings on the issue. The BA case was heard in Strasbourg together with three other applications by UK citizens, including one by the British nurse Shirley Chaplin, who brought her case to ECHR after being moved to a desk job because she refused to remove her cross on a chain while in nursing uniform.

Unlike Mrs Eweida, Ms Chaplin had her case thrown out by the ECHR after it ruled that the original decision against Ms Chaplin’s display of the cross at work was justified on the basis of health and safety for patients.

According to this survey, a majority of the British public disagree in principle: 70% of respondents said it should be allowed to wear a chain necklace with a Christian cross while working as a nurse, versus only 22% who said it should not be allowed and 7% who selected “Don’t know/prefer not to say”.

Strong support for wearing the kippah, but not the burka

Looking at the second and third surveys, majority opinion towards wearing a kippah to work follows broadly similar patterns as those towards the crucifix. Strong majorities said it should be allowed to wear one while working as a flight attendant (68%), as a nurse (60%), as a teacher (68%); and as an accountant (77%).

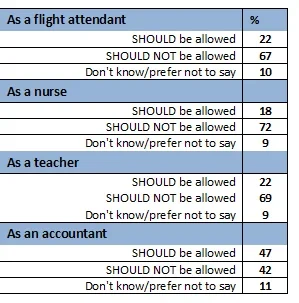

There are clear limits, however, to British support for religious clothing at work when it comes to the burka.

In the second survey, the question included a short explanation about the burka, with respondents being asked:

“Thinking about religious clothing and symbols, the burka is a loose item of clothing worn by women in some Islamic traditions for the purpose of covering a female's body and face when out in public. Do you think people in the UK SHOULD or SHOULD NOT be allowed to wear a chain necklace with a burka while working in the following roles?

<1> As a flight attendant?

<2> As a nurse?

<3> As a teacher?

<4> As an accountant?”

Here the results show strong opposition to being allowed to wear a burka while working in three out of the four roles – as a flight attendant, a nurse and a teacher:

Mixed views on the right to wear the burka in non-practical/non-public roles

Part of this opposition could relate to practical issues regarding the burka, which some respondents might presume rightly or wrongly have a greater physical impact on certain activities than either a kippah or small cross on a chain necklace.

It was for this reason, however, that we included the role of accountant in the study.

In the two surveys investigating attitudes to the crucifix and the kippah, support for wearing the item as an accountant was even stronger than it was for the other three roles: 85% overall support for wearing a crucifix in the role of an accountant, versus 81%, 70% and 77% respectively for working as a flight attendant, nurse and teacher; similarly, 77% overall support for wearing a kippah in the role of an accountant, versus 68%, 60% and 68% respectively for working as a flight attendant, nurse and teacher.

In the case of the burka, attitudes towards the role of accountant remain mixed.

Respondents show overall support for being allowed to wear a burka while working as an accountant, but only just, with 47% saying it should be allowed, versus 42% saying it should not be allowed and 10% choosing “Don’t know/prefer not to say”.

This is also the only section of the study across all three surveys where demographic break-downs show any real difference in attitudinal trends.

According to results, Conservative supporters are roughly divided on the right to wear a burka while working as an accountant, with 44% saying it should be allowed versus 46% saying it should not. (NB: the difference between these groups is within margin of error)

Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters show greater support for accountants in burkas, but with still significant numbers opposed:

- 52% of those currently intending to vote Labour said it should be allowed to wear a burka while working as an accountant, versus 39% saying it should not and 9% choosing “Don’t know/ prefer not to say”.

- a similar 57% of those currently intending to vote Liberal Democrat said it should be allowed to wear a burka while working as an accountant, versus 34% saying it should not and 9% choosing “Don’t know/ prefer not to say”.

Are British attitudes to the burka “un-British”?

The above results help to portray two trends in British public opinion towards the question of religious clothing at work:

First, an overwhelming majority of Britons support the principle of wearing religious symbols at work, at least in the case of small items such as kippahs and crosses on a chain necklace.

This preference is overruled, however, in the case of the burka, where opposition to wearing the burka at work trumps support for the principle of religious expression at work. Beyond large majorities who oppose the right to wear to a burka in roles such as flight attendant, nurse or teacher, the country is also divided on whether this right should exist when working in roles that have no physical or public facing responsibilities, such as being an accountant.

These findings point towards a broader pattern from YouGov polling in recent years – namely that the British public has a general aversion to the burka, which includes a consistent majority of two thirds plus who support banning the burka in the UK as they have done in France.

This would mean not only barring it from the workplace, but making it illegal merely to wear one while walking down the street.

Damien Greeen, the current UK Minister of State for Police and Criminal Justice, has stated that such a ban in the UK would be “un-British” and at odds with the UK’s “tolerant and mutually respectful society”.

As this study suggests, however, British sensibilities for multicultural diversity potentially meet their limits at the burka.

See the full results of the YouGov-Cambridge survey about attitudes towards the Christian cross

See the full results of the YouGov-Cambridge survey about attitudes towards the kippah

See the full results of the YouGov-Cambridge survey about attitudes towards the burka

Follow @YouGovCam for updates on our latest research