After the Prime Minister shocked the nation by calling for a snap general election, YouGov's Joe Twyman sets out how well equipped each of the parties are for the forthcoming vote

It is safe to say that Theresa May’s announcement yesterday that she wants a general election has taken the public, politicians, and pundits by surprise. But despite the utterly different circumstances facing each of them, the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats all voted in favour of a June 8 poll earlier today.

Looking at the current polling data, however, it seems that while some parties will back the ballot based on strengthening their positions, others seem to be engaging in what could turn out to be an act of political hara-kiri.

The Conservatives

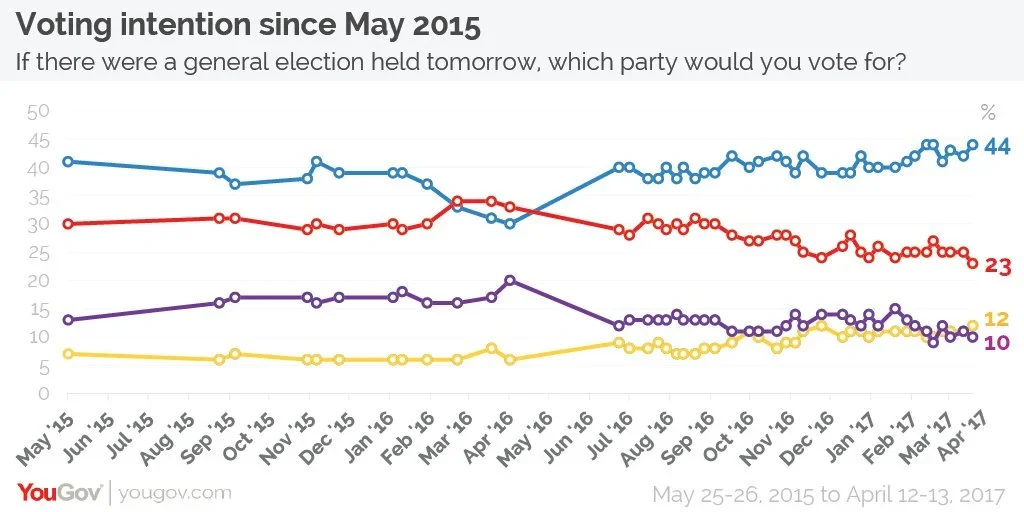

Both the recent reporting and the latest polling data suggests that Theresa May has called an election because she wants to win a large majority – possibly three figures. All the polling currently points to a big win for the Conservatives. They are more than 20 points ahead of Labour and well into the 40% range it is assumed is needed for victory. This has been the case for some time.

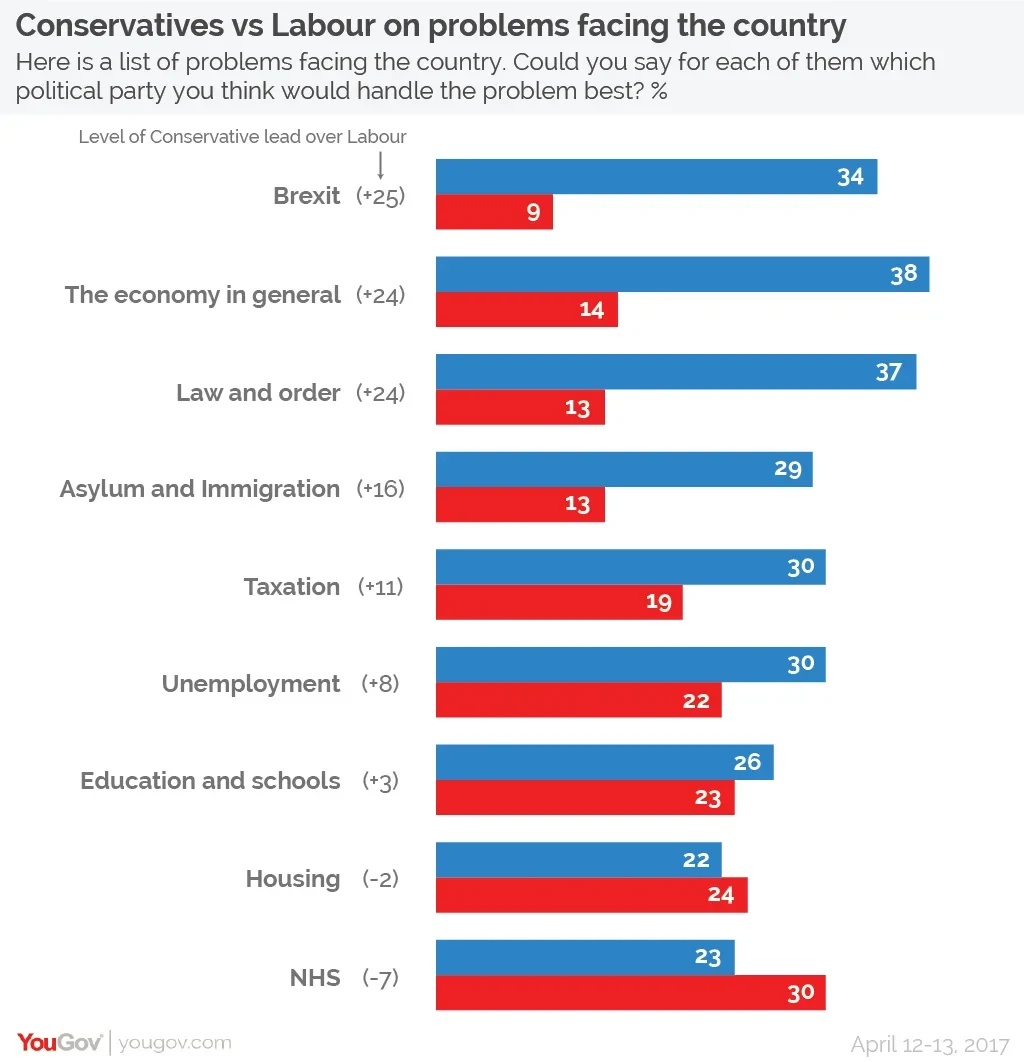

But more than that the underlying data also strongly points in the Conservative’s favour. As things stand at the moment, 50% of the electorate thinks May would make the best Prime Minister compared to only 14% who prefer Jeremy Corbyn. Tories also have strong leads on nearly all the major issues including the economy.

By winning Theresa May gets an electoral mandate of her own and also can work from a manifesto of her own making, instead of David Cameron’s from 2015. But if she secures a large majority she also hopes to strengthen her position within the still-divided Conservative party during the upcoming negotiations to leave the EU. Both Hard Brexiteers and even those Tory MPs at the other end of the scale wishing to remain (or at least a very ‘soft’ Brexit could potentially wield a lot of power under the Government’s current small majority. The Prime Minister hopes that an influx of new Tory MPs can dilute their influence in the Commons and prevent her being held to ransom.

It obviously remains very early days, however, and Theresa May’s very public U-turn on the decision to hold an election could be just one example of the pitfalls that both her and the party will need to negotiate if they are to maintain their current position of strength.

Labour

Theresa May will also hope that by going to the country now she can make the most of Labour’s current divisions. As you would expect, Jeremy Corbyn says he is up for the fight – after all, no politician would ever state that their party is not ready for an election and instead needs more time. The current evidence shows the shape and scale of the mountain the Labour party has to climb in order to gain power.

The NHS and housing are the only issue where they lead – and even then it’s not by much. More significantly, his party trails the Conservatives across both the economic management and leadership questions and no party has ever won a general election while being behind on both of these measures. While it is true that some of Jeremy Corbyn's individual policies play well with the public and see widespread support among voters, reactions to specific measures have historically been relatively poor drivers of voting intention.

In order to win Labour needs to hold on to what it already has but also to both regain and preferably even add to what it lost two years ago. There are many areas where it needs to pick up voters – winning back those it lost to the Conservatives from the South East, Lib Dems from the South West, and UKIP voters in the industrial North, not to mention enticing non-voters and new voters to turn out for them on 8 June. To date, the evidence, from polls but also by-elections and local council elections, suggests they haven’t yet managed this to a sufficient magnitude.

Naturally, things could change. Polling is only ever a snapshot of public opinion at that moment. To alter its current position, Labour will have turn the grass roots enthusiasm – as shown in Jeremy Corbyn’s two striking leadership victories – into votes. While turning things around would take a change far in excess of any historical precedent, the world of politics has changed a lot in the last few years and there are a few examples of the highly unlikely becoming reality.

SNP, Lib Dems and Ukip: Hard “Leave” and hard “Remain” parties

As it currently holds 56 of Scotland’s 59 MPs, it would be easy to conclude that the SNP doesn’t have much to gain from June’s poll. However, with the Prime Minister placing the election firmly within the context of Brexit and Nicola Sturgeon seeking a second independence vote in light of leaving the EU, there is every chance that the SNP will cast the general election on a referendum on Westminster’s relationship with Scotland.

Yet as the last Holyrood elections show, under the surface of Scottish politics a lot is happening – specifically Labour’s continued decline and the resurgence of the Conservatives under Ruth Davidson. There is a chance that the Tories could even gain seats in Scotland – but would they be at the expense of the SNP or Labour and the Liberal Democrats?

The Lib Dems will hope that the country has a re-alignment along Brexit lines Scotland did after its referendum. Based on current data this does not look very likely, but passions still run high on this issue for some – as the Richmond Park by-election shows – and as the only party committed to Remain, it is well placed to take advantage of any ardent pro-EU sentiment. While its position hasn’t really cut through yet, the oxygen of election publicity may change this.

Meanwhile UKIP has lost its figurehead, a lot of its funding, its expertise and – with the UK leaving the EU – what many regard as its primary purpose. Will this election see it lose ground in the wake of Brexit or will it continue as an anti-establishment force? Recent events in many countries (including Britain) how that the electorate has a desire for such a movement, but with the organisation seemingly coming apart at the seams, is UKIP in a position to deliver?

The most important thing to remember is that things can still change – in all sorts of directions. The next 50 days will answer many of these questions. There are events we know about ahead that could make a difference, from the local elections in May to even the French Presidential election. On top of this there will inevitably be the (as yet) unknown events we cannot predict. In each case we will have to wait and see which ones are the election’s talking points and which are its turning points.

Photo: PA

See the voting intention results here and the best party results here