A paradigm shift in consumer confidence has taken place on a global scale. The worst recession on record has forced everyone, whether rich or poor, young or old, to evaluate their personal and household finances, and to think about the implications for future generations to come. From the hedonist heights of a UK society that had been predicated almost exclusively on debt and credit for nearly a decade and the tacit assumption that growth was always inevitable, consumers have all come back down to earth with a bump over the last eighteen months, some immediately, others in a more protracted manner.

Here, I explore the extent to which such consumer confidence in the UK has been tarnished, and how it has evolved since the onset of the recession. The piece takes both retrospective and prospective views on what has changed in the British psyche during the recession. It looks at where new confidences have been found, and where old confidences have been lost. It hypothesises about the future and the extent to which, against a backdrop of ever more likely financial instability, consumer confidence will return to stability, remain at its current level, or increase.

I also explore the paradoxes and tensions requiring resolution in consumer’s minds vis-à-vis their financial choices. The financial services industry urges people to make ever more certain and medium- to long-term decisions about products (savings, investments, pensions, mortgages etc), but these are being made in an ever more uncertain and unstable world. The manifestation of the clash between psychological / social worrying and financial planning often results in consumer resentment, frustration, inertia and irrational behaviours in terms of choices and decision making concerning financial issues and their implications for lifestyle choices.

All data used here are the result of primary, proprietary tracking research undertaken by YouGov, the largest proportion of which has been derived from YouGov’s DebtTracker survey, a quarterly online survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,000 UK adults, as well as an additional 1,000 sample of respondents who are in ‘financial distress’ (people who claim to be falling behind with debt or credit repayment terms). DebtTracker has been running since July 2008, tracking, pre-, during, and post-recession response measures on a range of financial metrics pertaining to individual and household finances.

Other data sources mentioned include the UK/Markit HFI (Household Finance Index) – a monthly online survey of 2,000 adults representative of UK household incomes exploring optimism about spending patterns within UK households. There are also minor references to YouGov’s Prosperity Index, a proprietary index derived from a number of survey questions, all pertaining to household finances and people’s perceived confidence vis-à-vis what is happening in the wider economy. Incidental reference is also made to some questions asked on an ad hoc basis on YouGov’s Omnibus surveys.

The current state of play of household finances

It would seem appropriate to start by taking a look at UK household finances.

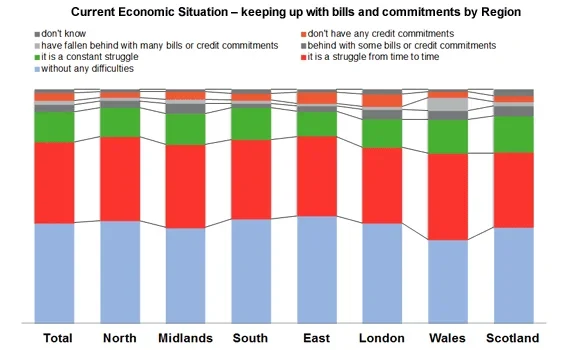

Firstly, in terms of the extent to which individuals are keeping up with bills or credit repayments, Wales (37%), followed by Scotland (32%), fares the worst in terms of people still 'finding it a struggle from time to time', according to YouGov’s latest (June 2010) DebtTracker findings. London is the region least affected, with 4 in 10 Londoners saying that they are currently keeping up with repayment obligations without any difficulty.

However, the number of people claiming that they are ‘sometimes’ or ‘more often than not’ short of money, and struggle to last until payday, decreased rather markedly between February and June 2010. Consistently, between July 2008 and July 2009, 53% of the UK population claimed to be struggling somewhat until payday. That figure peaked at 56% in November 2009, but decreased to our lowest yet reported figure of 43% in June 2010. In other words, householders are seemingly finding themselves on the road to recovery, with household finances in a better state now than they have been for over 2 years. This also coincides with the largest proportion of people saying that they 'never struggle until payday' (31%) in June 2010, in comparison with an average of 26% for all DebtTracker waves prior to this year. Of those living in the South of England 6 in 10 ‘hardly ever’ or never” struggle until payday according to our latest figures, whereas in Wales that corresponding figure is 4 in 10: in other words, the further away from London and the more rural the area, the harder the struggle! It is also people living in Wales and Scotland who claim to be likely to borrow more in the next 6 months, whilst people in the South and Southeast of England are least likely to borrow more in the next 6 months.

Overall, however, when asking the population to comment more generally about their financial circumstances over the past 6 months, people do appear to be coping much better in 2010, with a small decrease on the 2009 figures of respondents saying ‘things have got a bit worse’ or ‘much worse’ for them financially. Correspondingly, there has been a similar, small (1%) increase in respondents saying ‘things are better’. When comparing people’s present financial position with their position 12 months ago, it is the North and the East of England that think that their already distressed financial position has ‘remained the same’ or ‘got worse’ over the last 12 months compared to other regions. The North-South divide is thus very much still at play.

The ‘financially distressed’ segments of society are also struggling more than ever before when it comes to repaying ‘other debts’. In July 2008, only 13% of those behind with bills for more than 3 months were behind with ‘other debt’ commitments. That figure has risen steadily since then, peaking at 31% in February 2010 amongst this distressed sample, showing how the real challenges of recession are hitting the already vulnerable the hardest. It also shows that trying to keep up with crucial living costs, e.g. utility bills, phone bills, council tax and rents etc., is to the detriment of clearing ‘other debts’ such as store cards, credit cards and unsecured lending.

Daily spend

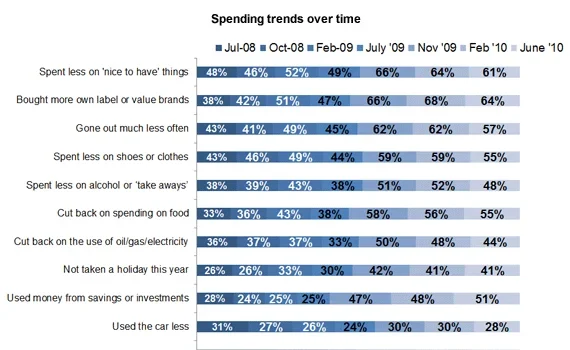

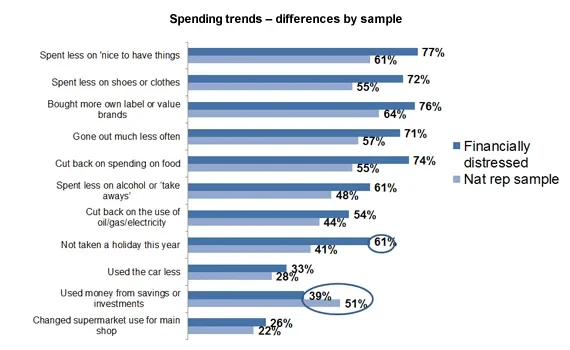

When considering household spend, fewer people are now falling behind with utility bill and council tax repayments than in the run up to and during the recession. However, in order to cope with mandatory payments, cutbacks are evident across the board elsewhere, with consumers cutting back on almost everything including ‘nice to have’ items, food and clothes. Many are also foregoing holidays.

People are also seeking out the ‘own label’ brands (the most marked shift in figures 2 and 3, below) and are going out much less often and cutting back on alcohol. Also, 5 in 10 are cutting back on food, suggesting that a new stoicism is emerging out of the detritus of the previous decade of decadence. This is particularly so for the financially distressed segment of society.

More positively, a larger proportion of people now expect to spend more on high-ticket items or purchases for their homes, such as carpets, curtains, furniture, double glazing, cookers, fridges, washing machines, televisions, computers and DVD recorders etc., than last seen in Autumn 2008.

Neither a lender nor a borrower be

Consumer borrowing levels over the last couple of years have either stayed the same or gone down across all retail borrowing categories, with the exception of the credit card category, where we have seen a slight increase in borrowing.

Those in financial difficulty are still turning to unsecured personal loans as a means of obtaining credit. In fact, the figures amongst those in distress who turn to unsecured lending are markedly on the up.

We have also seen a significant increase is people obtaining loans from family, mail order catalogues and DSS/social fund loans. We can hypothesise that a range of factors are at play here, including: consumers no longer being able to use credit cards as a payment mechanism because they have already maximised their existing limits, and/or have been denied additional credit limits with their current and/or other credit card providers. Consumers have also been refused additional borrowing on secured credit, either because of existing debt burdens and/or lack of loan availability. The 'credit crunch' is thus still very much a reality, even though the UK might technically be out of recession for the time being.

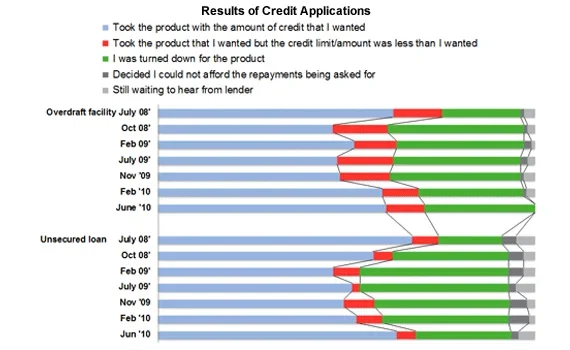

That said, creditors are showing some small respite in lending criteria, and this might be another reason why many people are now claiming to be coming out of financial difficulty. Of those who have taken out an overdraft facility or loan, it would seem that more people are now able to take a product with the amount of credit requested than at any other point since July 2008. Fewer people, however, are now able to take out the amounts requested via unsecured loans than during pre-recession levels.

Overall, a telling indicator about the psyche of UK PLC consumers is their agreement with the statement ‘Borrowing has become a way of life’. In July and October of 2008, when most people were still largely oblivious to the impending economic meltdown in the UK and elsewhere, over 60% of people agreed with the above statement. By June 2010, this figure had dropped dramatically to a 35% level of agreement, indicating strongly that borrowing had quickly gone out of fashion. Very much in line with the reality shock that hit consumers around Christmas 2008, people started to realise that the unprecedented and excessive borrowing of the early 2000s was unsustainable.

In short, there was a paradigmatic and substantial shift in the UK psyche towards the end of 2008. A decade of hedonism and financial irresponsibility had been exposed. It was time for each individual and each household to evaluate, face up to the truths and re-prioritise their finances, starting immediately with tackling the debt burden that is still a chain around many people’s necks. Accordingly, there has been a decrease in the number of people who use their overdraft facility, as well as a decrease in the number of people who are usually overdrawn by the time they get paid according to our latest DebtTracker survey data (June 2010).

It is striking that this trend is further corroborated via agreement to the questionnaire statement, ‘companies lending money have only themselves to blame if people stop repaying’. 57% agreed with this statement when we first asked it in July 2008. This figure has been in steady decline with our latest figures (June 2010) showing only 47% net agreement. The majority of consumers have awoken to the reality of the need for a renewed onus on individual financial responsibility, which arguably had been pretty much lost for a decade or so.

There has also been an increase in the number of people seeking debt advice since November 2009. Among the financially distressed sample of those in financial difficulty, the most preferred method of obtaining debt advice is face-to-face (42%), followed by phone (36%), and websites (17%). The low latter figure compared to overall internet usage and penetration figures might, in part, be due to the access (or lack thereof) to technology amongst a financially distressed sample. Technological and general literacy issues might also be at play.

Positively, the number of bankruptcies and IVAs (Individual Voluntary Agreements) has remained consistent over the past 6 months, but there was a 1% increase in the number of DMPs (Debt Management Plans) between November 2009 and February 2010. By our calculation, this means that there are now approximately 787,500 people in the UK with a DMP.

Hypothetical increases in spend

Thus said, when asking consumers about a hypothetical increase in their utility bills overall, only 4 in 10 people could cope with such rises. Those already in financial difficulty say that they could not cope at all. Similarly, when asked about a hypothetical 20% increase in council tax, only 4 in 10 could cope without any difficulty, while those already in financial difficulty could not cope at all. Part-time workers are also the segment most likely to suffer in relation to any additional increases to the cost of living.

Overall, YouGov’s multiple data strands all point towards a extraordinarily disturbing picture regarding the lack of adequate savings amongst UK householders. Our latest DebtTracker data (June 2010) shows that 1 in 5 people have less than £500 in liquid savings, with a further 5 in 10 of the population having less than £10,000 that is easily accessible. That is a staggering 7 in 10 people who are less than a few paydays away from personal financial disaster. This figure does not factor in a debt-to-savings ratio, i.e. it is possible that amongst the 70% of the population with what might be termed moderate levels of savings, there will be a proportion of whom who have greater levels of personal debt (excluding mortgages) than their levels of saving per se. Initiatives such as the FSA’s money made clear or NS&I’s ‘You and your money’ are all welcome additions to assisting consumer financial literacy. However, the fact remains that debt-to-credit ratios are staggeringly out of proportion in the UK compared to most other Western European counterparts.

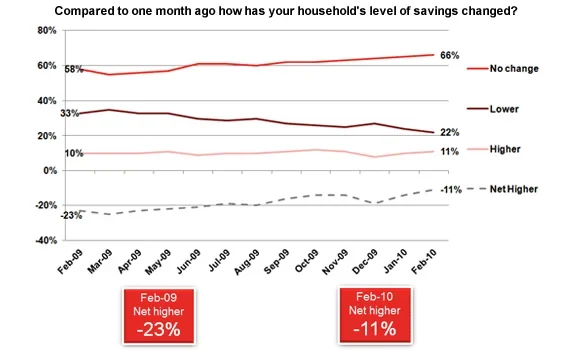

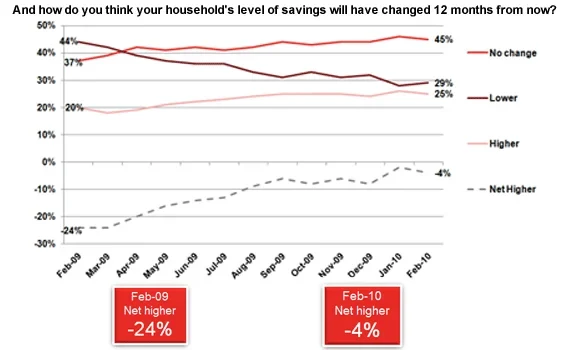

Data from our YouGov/Markit survey shows that net month-on-month household saving is still in negative territory, although the outlook is a little rosier than during the height of the recession and looks more positive in terms of the outlook for the next 12 months. Pensions and life assurance appear to have been most affected, with more people cutting back in these two areas than more short-term areas such as PPI, IPP or PMI.

Pension woes

People are also worried about the future outlook vis-à-vis their personal pension. In fact, uncertainty over how to prepare for pensions is growing. 4 in 10 people felt that they were preparing adequately for retirement in 2009, but that figure had dropped to 3 in 10 by 2010. There has also been an alarming increase in the number of people who simply do not know whether or not they are preparing adequately for retirement, rising from 6 percentage points to 18 percentage points in a year. Such an increase will no doubt be in part due to increasing consumer awareness about market volatility and personal experiences from having been affected or knowing people who have been affected, e.g. not receiving the yields anticipated and marketed by pension providers during the good times.

Such inadequate or at least uncertain pension provision, coupled with longer-life expectancy and projected population figures of 70 million by 2020 means that a return to economic prosperity looks like it will be an insurmountable challenge for decades to come. The financial services industry should be worried that significant proportions of the population have been cutting back on contributions to protection and investment plans, and this trend looks, anecdotally, to have continued throughout 2010.

The impact on stress

Interestingly, when asking people about the extent to which they feel likely to be made redundant in the next 6 months, it is the younger age group of 18-34s who feel that they are most likely to be made redundant, with 19% saying that they are ‘very likely’ or ‘likely’ compared to 8% of 35-54s. Overall, 1 in 10 of the population is still fearful over his/her job for the next 6 months, and a further 1 in 10 is, at best, uncertain.

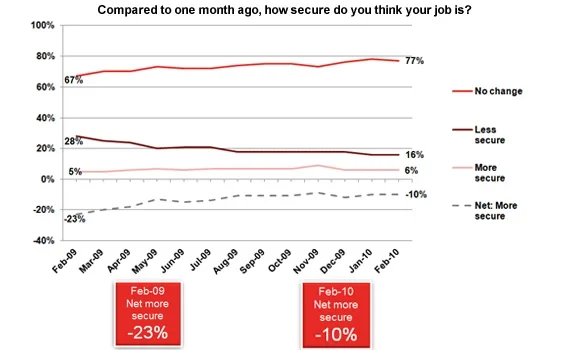

Good news overall, however, is seen in data from our YouGov/Markit household finance index, which shows that job security appears to be stabilising, with net scores for job security getting better between February 2009 and February 2010.

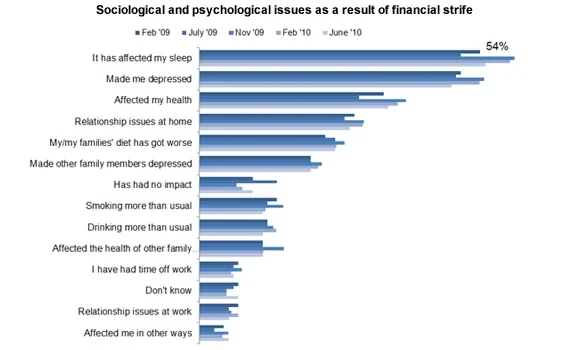

Despite such glimmers of regained positivity, finance-related anxieties in general point towards an alarming increase in new forms and manifestations of psychological and sociological phenomena. In turn, these further affect the economy’s ability to return to prosperity. For example, 5 in 10 are losing sleep over the recession, and 5 in 10 are being affected by depression to some degree as a result of the economic crisis. Finance-related anxieties are also affecting people’s health in general and are creating relationship issues for many as figure 8 indicates. Worryingly, these anxiety trends had been steadily on the increase since our July 2008 data, until February 2010. The June data set, however, shows gentle signs of pressures and burdens easing.

It is likely that the NHS and private medical sectors alike will experience a whole new raft of physical and psychological ailments and physical symptoms never before witnessed in the UK. This marked bi-polar shift from ‘Positive Mental Attitudes’ to ‘Negative Mental Attitudes’, coupled with the a new consumer realism about the tough times ahead are creating a new British psyche that we do not yet know how to manage collectively and to our mutual advantage.

An issue of trust

With an ailing British psyche come issues of trust and cogent decision making. Consumers have had their fingers burnt in the economic meltdown. Many thought they were making sound investment decisions in property, savings and investments, pensions etc., only to discover that the value of their wealth had been, at best, inflated, and, at worst, false all along.

Many people feel let down by a system and by institutions that had promised, and often claimed to guarantee, to protect them and their assets. For those who have had the rug pulled swiftly from under their feet, it will take financial services institutions a long time to rebuild constructive dialogue and long-term, meaningful relationships with their customers again. Any form of marketing communications or advertising that ignores either explicit or implicit acknowledgment of consumer’s financial plight will further alienate and disengage consumers, rather than start to pave the road to recovery and rebuild constructive dialogue with potential audiences. It is important to consumers that financial services institutions acknowledge the major part they have played in the crisis, and that they have all been culprits to varying degrees. Explicit apologies will work if they are genuine and consumers feel that lessons have been learned. Simply carrying on with marketing strategies that ignore what has happened over the past 24 months or so will come under fire.

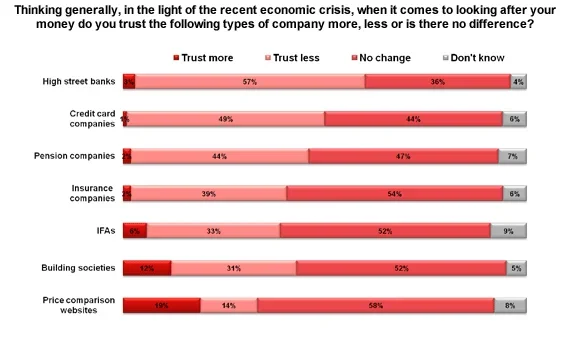

YouGov has statistical evidence to corroborate this critique. When we posed the question: ‘Thinking generally, in light of the recent economic crisis, when it comes to looking after your money do you trust the following types of company more, less or is there no difference?’, High Street banks are trusted less by 6 in 10 people, followed by credit card companies being trusted less by 5 in 10 people. 4 in 10 trust pension and insurance companies less, whilst 3 in 10 trust IFAs and building societies less. Interestingly, the winners look to be comparison sites with 1 in 5 trusting these more since the economic crisis.

This indicates a shift, albeit a small scale one, in which consumers increasingly shape and take responsibility for their own personal finances online, rather than relying on the traditional, direct or face-to-face channels. Perhaps we should question the extent to which the industry is really ready to cope with a genuine shift in consumer pro-activity when it comes to sorting and managing their personal finances. There is also a question as to whether the industry is creating speedy and efficient enough processes for when people are on the tipping point of a product purchase online. Many financial products still require several days before a decision can be made on the success of the application, or, more often than not, require consumers to phone/visit a branch, despite having just engaged with a lengthy online application process and provided all of the requisite detail for financial services companies to be able to make the decision as to whether the applicant is a creditworthy or eligible candidate for the product in question.

Perhaps there is a paradox herein. As some banks revert to a more traditional, customer-centric service with extended branch hours/approachable and friendly staff-based propositions etc. (e.g. the new Metro bank branches in London), many younger, more financially astute customers simply want to be in charge of their own financial destinies. Rather like the advent of digital TV with pick-and-choose scheduling, i.e. non-linear rather than linear models of revenue generation, financial services companies need to learn to think about new models, products and services for the younger generation who are the wealth holders (or perhaps permanent debtors?) of tomorrow. Online is the preferred communication channel for the younger generation, yet few financial services companies appear to have cottoned on to the real and genuine power of online activity, not just as a marketing and brand building or call-to-purchase tool, but as the most efficient, transactional route for under 34s in particular. The PC/Mac is a physical extension of many young people, much like the ‘Club Card’ fob is part of the personal identity that Tesco wants to create for its customers. I cannot think of a single financial services company that has fully maximised or harnessed the power of Online in marketing to its younger, more affluent customers in particular.

Is the future bright?

Despite systemic trust issues and a rather bleak picture when it comes to the orderliness of UK household finances, there is a tacit optimism and a sense of anticipation about the future.

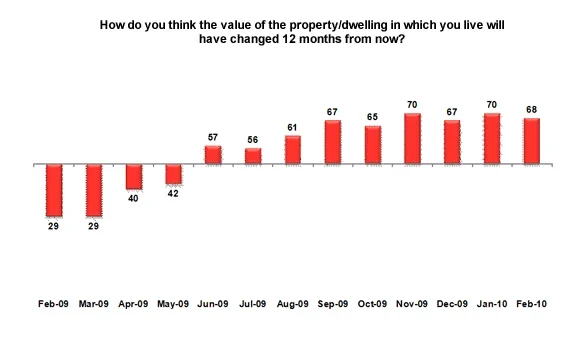

29% of the UK population expect house prices to rise between 0% and 10% over the next 12 months, which is a greater level of optimism than ever seen since YouGov has been asking this question on its DebtTracker survey. Most people expect house prices to recover within the next 3-5 years, suggesting that a medium term mindset is dominating financial behaviours.

Comparable data from our YouGov/Markit survey points to an upward trend in terms of how secure people feel about the value of their property. Positive scores have been seen on a monthly basis since June 2009, having been in negative territory for several months previously.

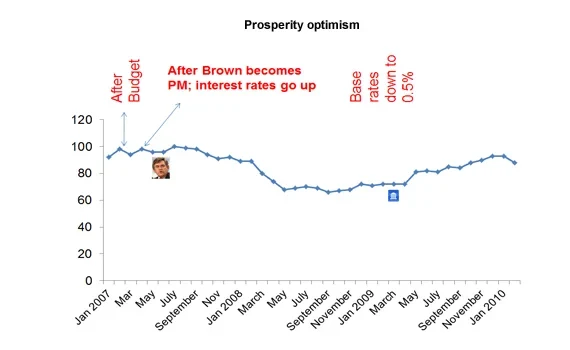

This is further corroborated via data from our prosperity index with prosperity sentiment largely declining in line with interest rate cut announcements, but it has since stabilised, if not started to increase between March 2009 and January 2010 onwards in particular. However, there are elements of doubt creeping back in as we edge towards a period of potential political uncertainty, and as Britain’s deficit continues to deteriorate, with widespread severe cuts to Public Sector budgets after the General Election and Spending Review.

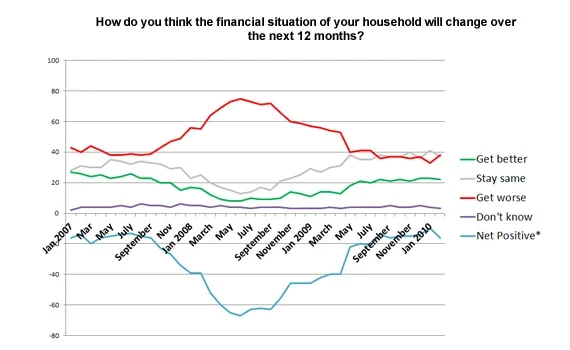

And while more and more people were gradually expecting their household finances to get better during the course of 2009, net consumer positivity with regards to a question from YouGov’s prosperity index , ‘how do you think the financial situation of your household will change over the next 12 months’, is starting to show an incremental decline again, with more people expecting the situation to get worse in 2010 versus in 2009.

The same negative disposition applies towards consumers’ dissatisfaction with their family’s likely standard of living over the next 12 months. Fewer people are satisfied with this outlook now, compared to higher levels of satisfaction witnessed between September and December 2009.

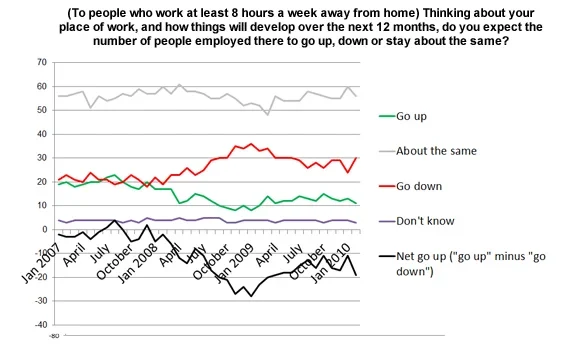

Fewer people are confident that their workplaces will grow over the next 12 months, with net agreement amongst those expecting the number of people employed in their workplaces to go up in the next twelve months on somewhat of a downward spiral since the turn of the year.

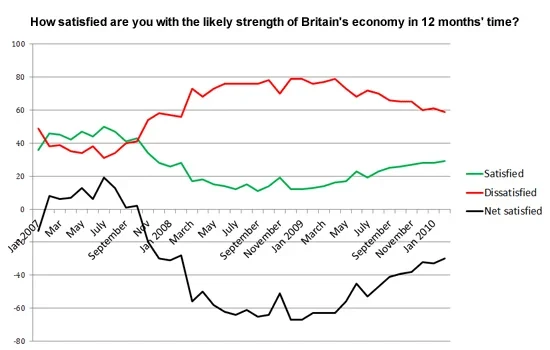

This, however, is at odds with consumers’ likely satisfaction with the UK economy over the next 12 months. Here, we see more people adopting a more optimistic outlook, purporting to be more satisfied with the economy than last seen in early 2008, that is, pre-recession. Election hopes and promises might be impacting in part on sentiment here.

In conclusion...

This article has painted a mixed picture of how people’s attitudes and actual spending behaviours have changed since the onset of the credit crunch, then the recession, and what now feels like the slow road to recovery. While things have stopped getting worse, for many people, the recession is still painfully real, and it is this that drives financial behaviour.

Although there are some ‘green shoots’ to be seen as far as consumers are concerned, our most recent data from a variety of proprietary financial indicator datasets makes us hypothesise that these will be short-lived.

The uncertainty about UK PLC’s position as a leading global player, coupled with the innate and now well entrenched fears about job security, individual indebtedness and UK’s credit rating worthiness, is fostering a nervous, cautious and more subdued consumer.

When it comes to savings and investment products in particular, financial services organisations should never forget that they are, after all, playing with consumer’s money. They are being contractually entrusted to look after and safeguard it and ideally, make it grow. For many consumers, they feel the contract has been rather one-sided, with banks able to treat customers as they choose, with little return or no regard for individual circumstances or personal situations. The recession has reminded us all that we may well need swift access to our cash, and, as a result, there has been a heightened desire and expectation for savings to increase. However, the huge lack of trust in traditional financial institutions has left consumers unsure of where to turn. There are some short-term winners, such as comparison websites as mentioned above. However, the real challenge is for institutions to create sustainable, truthful, honest, transparent and open dialogues with their customers. No more false or grossly over-egged promises. Simple offers from trustworthy sources will be the ones that do well. Anything less will not cut the mustard amongst consumers, who have awoken rather abruptly from their financial slumber, and who, as a consequence, have undertaken a radical and rapid post-mortem on their household finances.

Even with all the data and insights discussed above, there are still many questions to answer. Although Joe Public is more financially savvy and politically engaged (or voluntarily disengaged) than at any point in modern history, experience tells us that, in the long term, leopards rarely change their spots. On that basis, will some of the more thrifty, frugal consumer trends identified in this paper, such as cutting back on luxuries and nice-to-have things, withstand the test of time, or, as soon as we have had several consecutive months of moderate (as opposed to sensationalist) doom and gloom, will the ‘same old, same old’ apply?

Will quality rather than price start to become a bigger priority for people again, or, will everyone continue to boil everything down to a simpler, common denominator, namely cost, given the hard times that undoubtedly lie ahead? Will people continue to exert conservatism or stoicism vis-à-vis their personal and household spend, or will they simply revert back to the decadent days as soon as the media green light is received that we are out of trouble?

Will consumers remain relieved and released because their values and morals have been challenged, because they have self-reflected and changed their ways, or will the ‘old’ model of capitalism triumph, coming back with an even bigger vengeance? Will we simply accept that debt is indeed the new way of life and create new financial models around the assumption that most people will not be able to sail through life with their finances constantly in the black? Will we simply accept that a society predicated on debt and credit is to be the norm, at least for the foreseeable future, and will new forms of derivatives or financial instruments emerge to structure economic society on this very basis?

Have consumers learned a genuine lesson, the pearls of wisdom of which we will impart to future generations, or, after a brief respite, will everyone continue to see ‘borrowing as a way of life’ and amend their lifestyle accordingly? It is well documented that Homo sapiens tends to revert to habitual behaviours in times of crisis. Perhaps the globally inter-connected modern citizen, who for the first time has education, social freedom and global access to global and instantaneous information, can change his ways.

Please note, this article was originally written eight months ago but was published recently.

This article is © Emerald Group Publishing and permission has been granted for this version to appear here. Emerald does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Emerald Group Publishing Limited.