The recent attacks by Islamist extremists in Paris, the worst atrocity Europe has seen for more than a decade, triggered plenty of concern about a rise in hostility towards Muslim minorities. Indeed, one self-proclaimed goal of Daesh (or "Islamic State"), the group who claimed responsibility for the attacks, is to sow discord between Muslim minorities and European majority populations. There have been many reports of abusive and hostile behaviour towards Muslims in the aftermath of the attacks, but those responsible are a tiny minority of the population, one whose hostility to Muslims may have predated the Paris atrocities.

Did Paris trigger a broader backlash against Muslims in Britain, and a shift towards more authoritarian or illiberal policies towards them? Thanks to unique new polling data collected immediately before and after the Paris attacks, we can give a firm answer to that question.

The answer is no. On a wide range of measures, we find no negative shift in public sentiment after Paris. In most cases, attitudes did not change at all. When they did change, positive shifts were more frequent than negative ones. While truly inclusive and tolerant principles are far from universal, they are resilient: the people who hold such principles mean what they say. They stick to their values under pressure.

Studying how people react to traumatic events such as terrorist attacks is hard to do, as such events are impossible to predict. To take advantage of any such shock to study the attitudes of resistance one must have, by chance, a survey looking at relevant attitudes in the field right before such an event occurs. We happened to be conducting a survey on democratic attitudes, including tolerance, preferences for surveillance and minority rights in the field with YouGov days before the Paris attacks.

With support from YouGov and Stanford University, we were able to repeat the survey immediately after the attacks, and thereby get a unique snapshot of how the public responded to the shock event.

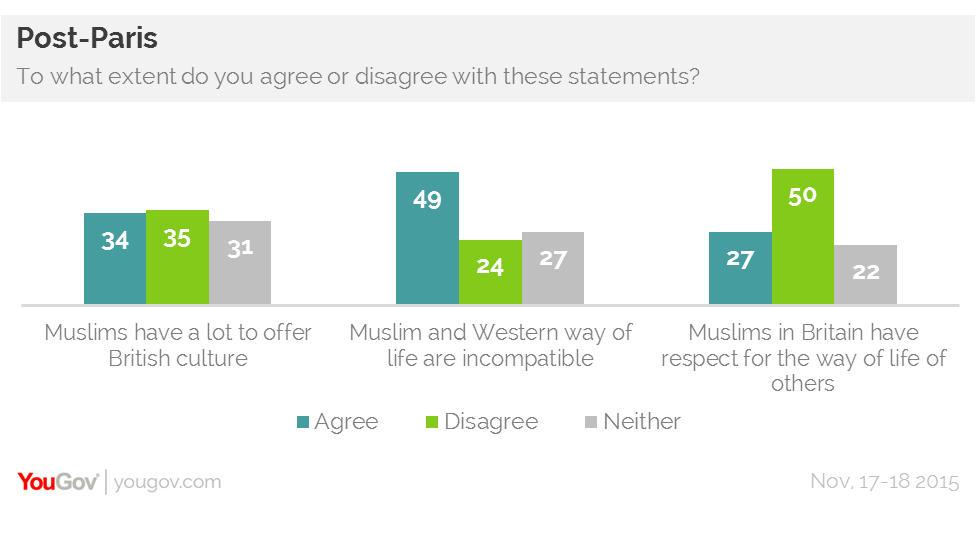

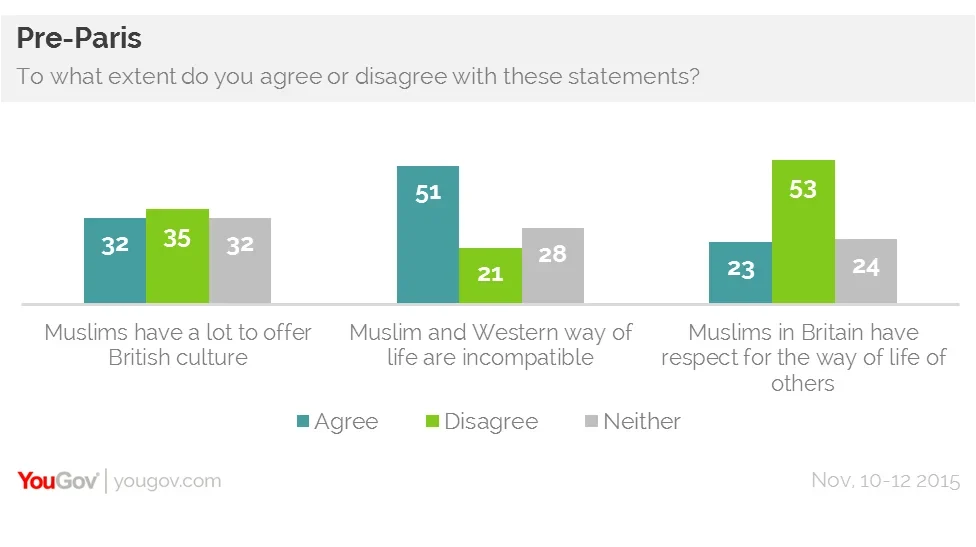

Our survey included a number of items on views about British Muslims as a group. We asked respondents whether they agreed that Muslims in Britain have respect for others' ways of life, whether British Muslims have a lot to offer the national culture, and whether the Muslim and British way of life are incompatible. If the Paris attacks produced a negative shift in views of Muslims, such items provide us with a good tool to detect it. But we found no negative shift at all.

Instead, as our table below shows, there was in each case a positive shift in views of Muslims: fewer people worried about a clash of cultures and more expressed appreciation for the Muslim contribution to British life. The move was modest in every case, and public concerns about Muslims remain very widespread, with between a third and half of respondents expressing negative views on these three items. But the Paris attacks did not worsen the situation, and may have encouraged more tolerant views among some.

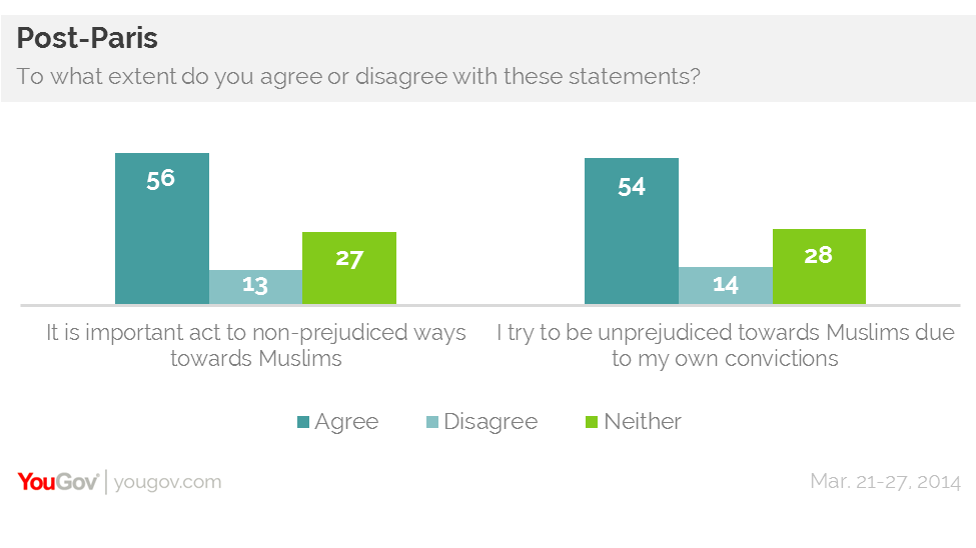

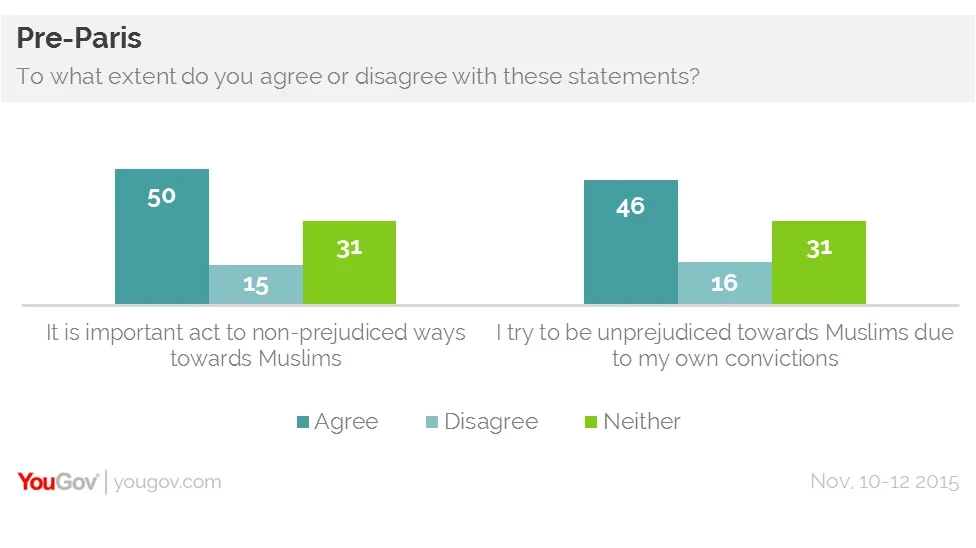

We also asked people questions about their motivations to control prejudice. This is an idea we have developed in earlier research, that many people regard being tolerant and inclusive as an important social value and are motivated to try and live up to it. Here, again, we find that the Paris attacks strengthened people's motivation to treat Muslims in a fair and inclusive way – and here the effects were much stronger. The proportion saying it was personally important to act in non-prejudiced ways towards Muslims, and to be unprejudiced as an expression of personal convictions, jumped after the attacks. It seems the attacks strengthened many people's resolve to act in a fair and inclusive way towards Muslims.

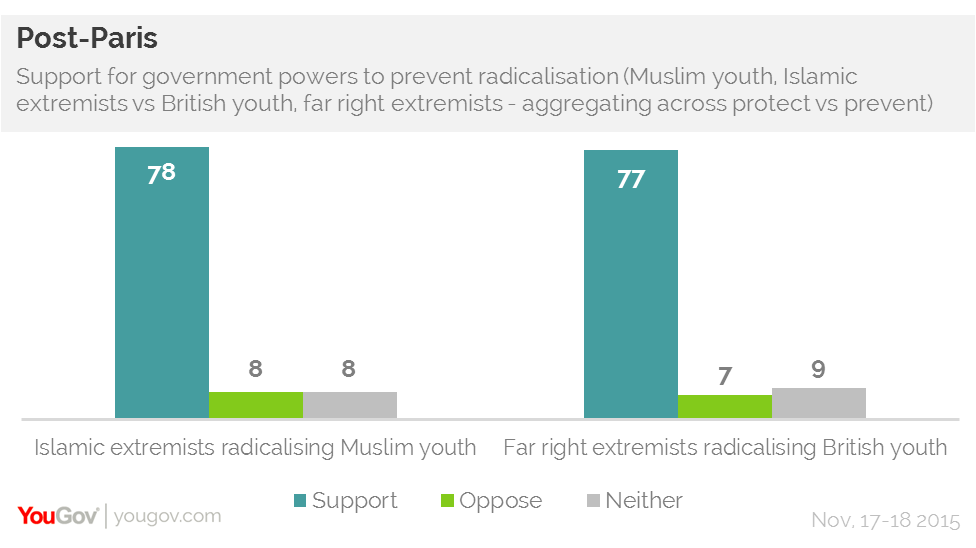

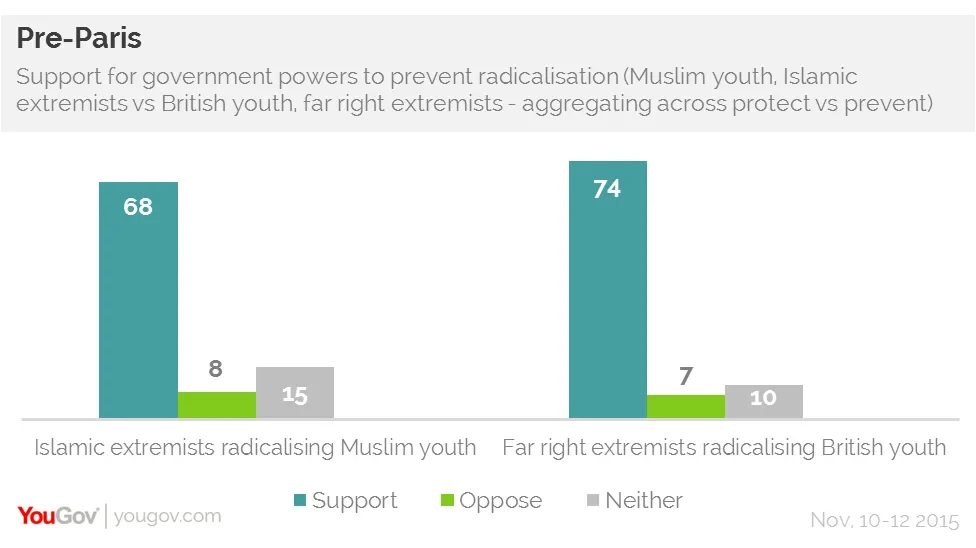

Our surveys also contained a number of experiments designed to tease out the conditions which affect voters' support for diversity and accommodation with Muslim minorities. The first dealt with security: we asked respondents if they would support or oppose enhanced government powers to combat radicalisation of young people by extremists.

We wanted to see if Muslims were "singled out" for harsh treatment on this issue, so we randomly assigned people to be asked either about powers to prevent Muslim youth from being radicalised by Islamic extremists, or British youth being radicalised by far right extremists. The inclusion of this question was particularly fortuitous as the received knowledge is that Islamic terrorist attacks lead to increased support for surveillance of Muslims, even at the costs of their civil liberties.

Here, again, we find cause for optimism. Powers to prevent radicalisation are very popular with voters, but they are just as popular when targeted at far right extremists as at Islamic extremists. Voters don't single Muslims out. They are equal opportunity opponents of radicalisation. What is more, the worst terror attack on European soil by Islamic extremists in a decade did nothing at all to change this. Powers to counter Islamic radicalisation became more popular, but so did powers to tackle far right radicalisation. Paris strengthened demands to tackle extremism, regardless of the source.

One final piece of evidence points concerns views of diversity. The Paris attacks occurred in a diverse and dynamic European capital. By coincidence, our survey also had an item looking at views about diversity in another dynamic European capital: London. It is worth pointing out that the post-Paris question has been asked before the country’s capital was mentioned in this context by Donald Trump, which would have confounded our results without a doubt. We asked people whether they thought London was better off or worse off due to its ethnic and religious diversity.

It would be perfectly natural for those considering this question after Paris to take a more sceptical view than those surveyed beforehand. In fact, the opposite occurred: British respondents were much more positive about London's diversity after Paris. Perhaps people were keener to embrace London's diversity as a way of rejecting the divisive fanaticism of the ISIS terrorists. Perhaps the attacks, by threatening the values we normally take for granted, made people keener to embrace them. Whatever the reason, many responded to the tragedy of Paris by celebrating the value of London's diversity.

In sum, what we find is resilient tolerance, on a number of measures. The share of people expressing inclusive, or liberal, or multicultural views was largely the same before and after the Paris attacks. This is not to say such views are universal. We found widespread hostility in both of our studies; liberal or inclusive views are often in the minority, particularly when it comes to views of Muslims as a group. The Paris attacks may have intensified the hostility felt or expressed by those who already viewed Muslims negatively. Reports of spikes in anti-Muslim abuse and violence would be consistent with this.

However, our study suggests that such incidents reflect the anger of an already hostile minority rather than a broader negative shift in the public mood, which was unchanged more or less across the board. This broader resilience is, we think, both surprising and important. It is natural to think that many would shift their views on these divisive issues in reaction to a major atrocity. They did not. This is a cause for cautious optimism - the difficult accommodations and negotiations that life in a multicultural society will require will be easier to make if moderate voters on both sides of the issue reject efforts by extremists to set the agenda. In Britain, our study suggests, that is what happened after Paris.

This article was written by Rob Ford and Maria Sobolewska of the University of Manchester