A preliminary analysis of what might have gone wrong with the general election opinion polls

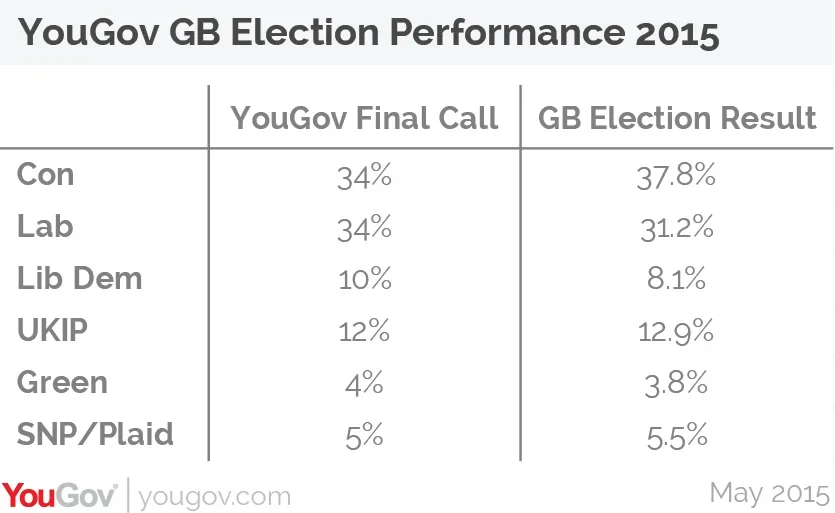

Our final call for the 2015 general election showed Labour and the Conservatives neck-and-neck, but the actual results gave the Conservatives a lead of around seven points. For any polling company, there inevitably comes a time when you get something wrong. Every couple of decades a time comes along when all the companies get something wrong. Yesterday appears to have been one such day. Below is a table of YouGov's final call for each party compared to the actual result:

In particular, the all-important margin between the Conservatives and Labour was significantly off. When something like this happens there are two choices. You can pretend the problem isn't there, doesn't affect you or might go away. Alternatively, you can accept something went wrong, investigate the causes and put it right.

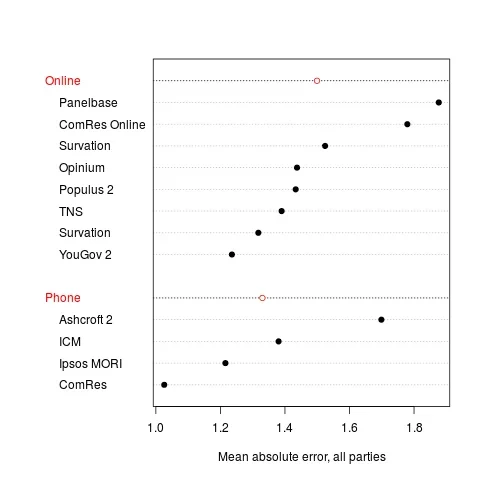

The polls in the run up to the 2015 general election were wrong. In the final eve-of-election polls and for several months before the election the polls were consistently showing Labour and Conservative roughly neck-and-neck. Individual polls exist that showed larger Conservative or Labour leads and some companies tended to show a small Labour lead or a small Conservative lead. However, no company consistently showed anything approaching the seven point Conservative lead that happened in reality. Chris Hanretty of the University of East Anglia and electionforecast.co.uk has already analysed the mean average error of all the polling companies which we reproduce below. It shows YouGov's position in relation to the other major polling companies - ahead of most, but not good enough:

The difference between the polls and the result was not random sample error – it looks as if there was some deeper methodological failing.

It is possible that was a late swing towards the Conservatives after the end of polling, but our re-contact survey on the day found no significant evidence of this. Other companies who polled on the day may have had a different experience, but even so, a late swing large enough to create a seven-point swing in a single day seems unlikely.

We can also confidently rule out mode effects (whether the survey was conducted online or by phone) as the cause of the error, as the final polls conducted online and the final polls conducted by telephone produced virtually identical figures in terms of the Labour/Conservative lead.

The fact that both telephone and online polls experienced the same understatement of the Conservative lead also helps us rule out some other possibilities. For example, it doesn’t point to increasing use of mobile phones to be the cause or the problem (or at least, the sole cause of the problem) or it would not have affected online polls. It also doesn’t point to panel affect being the cause or the problem or it would not have affected telephone polls.

We have some ideas for potential causes of error. Given that the pre-election polls (where it is up to the pollster to accurately model likely turnout) were wrong but the exit polls (where the pollster knows for certain respondents have voted) were accurate, one potential cause of error may be the turnout models used.

Other things we will examine as possible causes of error will be differential response rates and how well current sampling methods are reflecting the British population. We will, of course, look with great interest at the findings of the British Polling Council inquiry into what went wrong and hope to learn from the experience.

What we are determined not to do is to jump to any hasty conclusions. We will take the time to fully examine and test all the possible causes of error, work out what the underlying causes are, and then put them right.