The four groups of election battlegrounds to watch – and what we know about them from the polling so far

It’s a truism that there isn’t one election on May 7th, there are 650. However, the brutal reality is that lots of them will behave much the same in terms of swing, and that in lots of them the outcome is a virtual certainty and they won’t matter. A good 450 or so seats we can be pretty confident won’t change hands this Thursday unless the polls are very wrong. We can actually boil down the election to four battlegrounds.

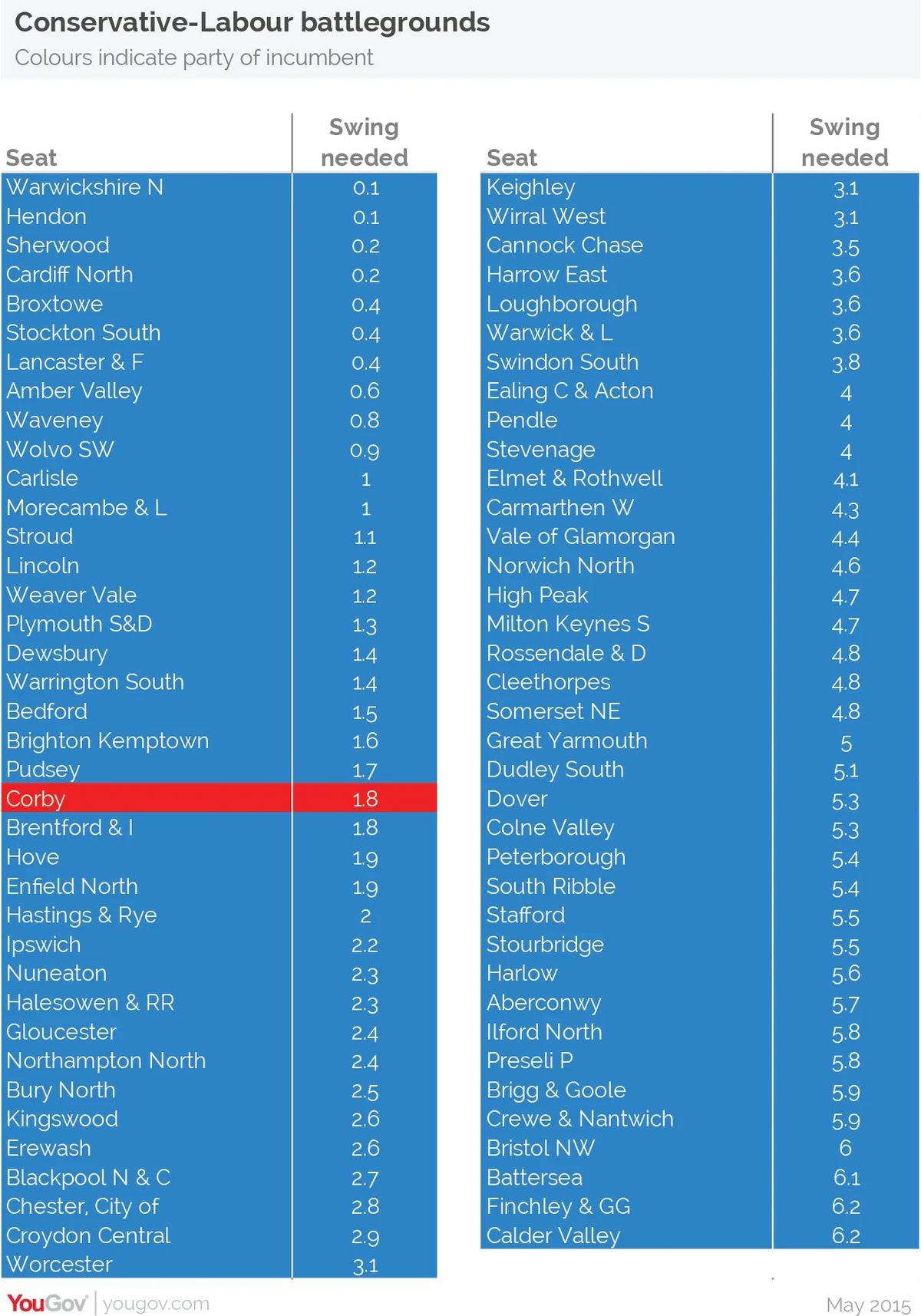

Conservative vs Labour battleground

The main battleground in determining which party will lead the government is that between Labour and Conservative. It’s also by far the largest – it’s true to say that the political geography of Britain has become ever more diverse since the days when almost every race was just Lab-v-Con, but the biggest single chunk of winnable marginals is still just that.

It’s also the battleground where good old uniform national swing remains a fairly good guide. It won’t predict individual seats – there will always be some seats with much bigger swings, some with more smaller ones – but in aggregate it should give a good picture. Overall current polls show a swing of about 3% or 3.5% from Conservative to Labour. In the Con-Lab battleground that should win Labour roughly forty seats.

However, there are two important caveats to this. The first is that almost all the Con-Lab battleground is in England & Wales, and GB polls are distorted by the completely different swing in Scotland. Labour’s vote is up by around 5 or 6 points in England & Wales, down by about 15 to 20 points in Scotland. If you look at the data in just England & Wales you find a Con>Lab swing nearer 5 points, which would win Labour around sixty seats.

The second is whether the swing in the marginal seats is the same as the swing in England and Wales as a whole. Looking at the historical data there is good reason to expect it won’t be. The vast majority of the Con-Lab battleground seats are being fought by first time Conservative incumbents who won the seat in 2010, this means they will be gaining an incumbent advantage they didn’t have last time, while in many cases Labour will be losing an incumbent advantage they enjoyed in 2010. Looking at data from past elections this impact is pretty consistent even if it is worth only a couple of percentage points (it’s worth far more for the Lib Dems). There is some evidence to support this – the recent ComRes poll of Con-Lab marginals found a swing of 3.5%. Looking at the broad sweep of Lord Ashcroft’s polls in these seats and adjusting the older Ashcroft polls to account for changes in the national polls since they were done the average swing comes out around 3.8%.

In practice this means the swing in the Con-Lab marginals may well be similar to that in the national polls, but only because Labour’s over-performance in England & Wales is cancelled out by Conservative over-performance in Con-Lab marginals. That means Labour gains from the Tories of around 40 seats, if the national polls are neck-and-neck (if the Conservatives are a point or two better, the gains will obviously be less)

Of course there will be variation between seats, so not all Con-Lab marginals with majorities below 7% will fall, there have been some constituency polls suggesting good chances of Conservative holds in marginals like Loughborough, Worcester or Kingswood. Equally though there will be some seats with larger majorities that do fall – London constituency polls in particularly have shown larger swings, so watch for places like Ealing Central & Acton or Finchley & Golders Green.

The SNP Landslide

The second biggest focus on election night will probably be the Scottish seats. What the story will be in Scotland is not in dispute, it will be a SNP landslide. The question is only the scale of that landslide. All the polling evidence gives the SNP a very large lead, varying between 20 and 35 points. The questions are where it ends up in that range, how accurate it is and how it translates into seats.

To deal with the overall polls first, I can well imagine that some polls in Scotland will overestimate SNP support. There have been huge shifts in party support since previous elections (and probably significant changes in the drivers of voting intention in Scotland) making it hard to model and weight Scottish samples. Equally SNP support is extremely enthusiastic – I can well imagine differential response rates becoming a problem. That said, polling error in Scotland probably won’t cause much of an upset because of the sheer size of the SNP lead – to put it bluntly, if polls give a party a 5 point lead and it turns out its actually a draw then it makes a huge difference. If polls give a party a 25 point lead and it turns out that lead is actually only 20 points it is not, in practice, such a big deal, even if the scale of the error is the same. The difference will only be between “vast landslide” and “huge landslide”. I cannot see the polls being so wrong that the SNP don’t get a crushing victory.

So how will the SNP landslide in votes translate into seats? Well, with a swing of this scale Uniform National Swing really does break down completely. UNS assumes parties shares of the vote go up and down by the same amount in each seat, but Labour cannot lose 20 percentage points in every seat in Scotland, it would give them a negative share of the vote in nine seats. The same applies to the Liberal Democrats. As a result of this floor effect, Labour and the Liberal Democrats must be losing more support in seats where they had more to begin with – their vote has fallen too much to be evenly spread across all of Scotland. This means that Labour and the Lib Dems could lose even more seats than suggested by uniform swing (and means even if the national share of the vote for the SNP isn’t as good as polls suggest, they could still get the sort of landslide in seats that the polls suggest).

The scale of the SNP surge is such that very few seats have any realistic chance of withstanding it. The most plausible ones are the very largest Labour majorities, the Glasgow North East, Kirkcaldys of the world, Jim Murphy in Renfrewshire East, the Lib Dem stronghold of Orkney & Shetland and perhaps the border seats (if the SNP don’t take Berwickshire, it is also a marginal between the Lib Dems and Conservatives).

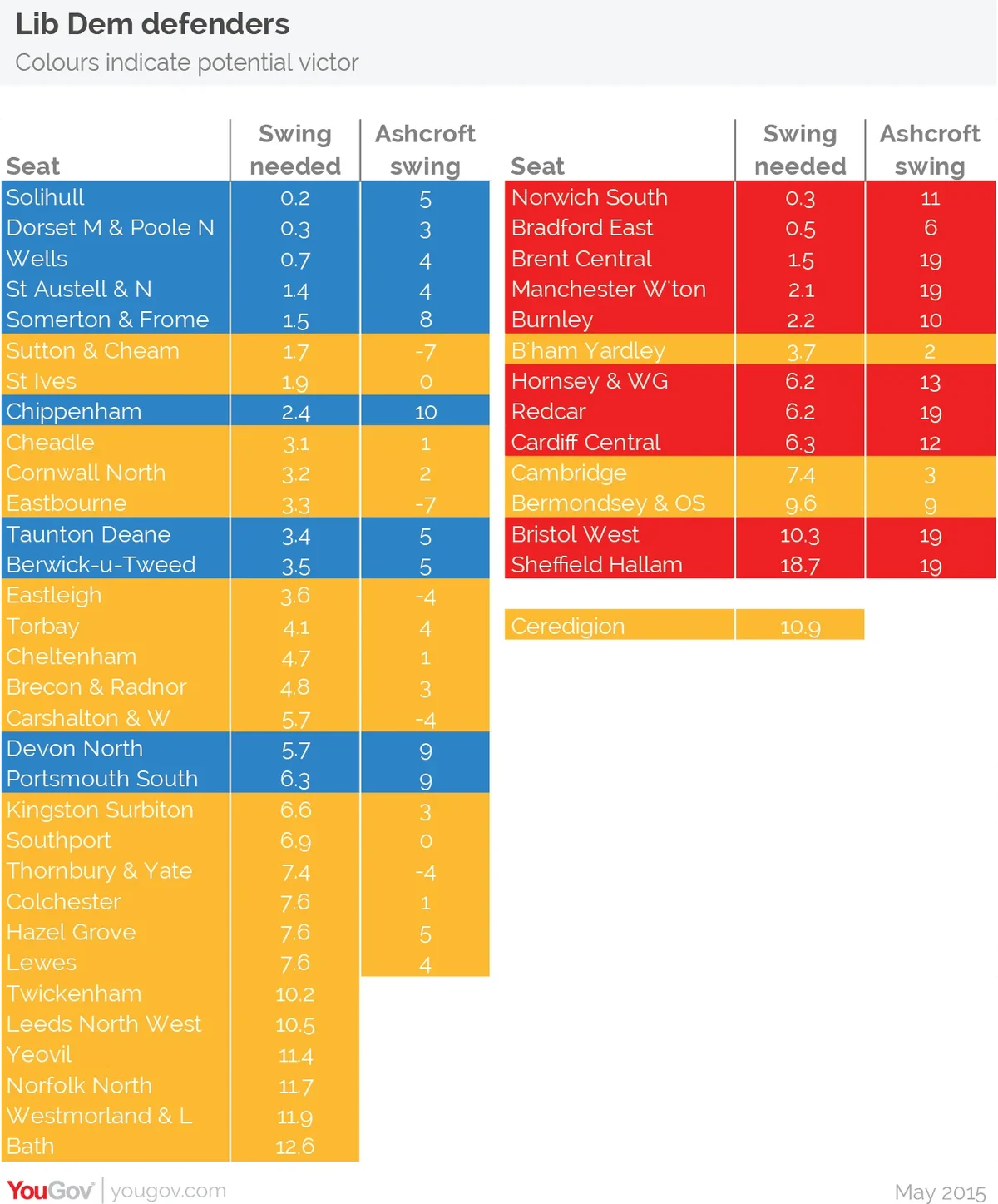

Liberal Democrat Defence

Given the Conservative party’s most viable coalition partner is the Liberal Democrats how many seats change hands between the two parties doesn’t make much difference to the electoral maths after the election. It is still obviously important for negotiations, party morale, the psychologically and politically important issue of who is the biggest party (and, of course, for who is the MP in those seats!). Liberal Democrat battles against Labour are far more important in terms of the hung Parliament maths.

The Liberal Democrats’ ability to win and hold seats has a famously limited relationship with their national vote share. In 1992 they got 18% of the vote and won 20 seats, in 1997 their vote went down to 17% but they more than doubled their number of seats to 46. In 2010 they gained votes, but lost 5 seats. How many seats they win has always been largely reliant upon their ability to harness tactical and personal votes in their areas of strength. That said, it’s not realistic to expect a party to lose half their national support and emerge unscathed. While I’ve seen a few claims for potential Lib Dem gains that aren’t completely ludicrous (Watford or Maidstone & the Weald, for example), generally speaking the Liberal Democrat election aim is to limit their inevitable losses as much as they can. This depends upon the demographics and political opponents in their seats, and the incumbency and entrenchment of their individual MPs.

In England and Wales the Liberal Democrats have 46 seats. In eleven Labour are the second placed party, in thirty-four the Conservatives are second placed (though in at least two of them, Sheffield Hallam and Cambridge, Labour are probably the bigger threat) and in Ceredigion Plaid Cymru are second placed. In the vast majority of the seats we have individual polls from Lord Ashcroft to give us an idea of how the race is looking. There are two extremely obvious trends – one is that the Liberal Democrats are collapsing where their main challenger is Labour, but holding up well where the main challenger is the Conservatives. The second is the sheer variation between seats, even within the LD-Con battleground and the LD-Lab battleground.

Ashcroft has polled all the LD/Con marginals that might feasibly change hands. The average swing in these seats was just over 2 points from LD>Con, enough to take about seven seats. However the swings ranged from ten percent LD>CON in Chippenham, to swings of seven percent from CON>LD in Eastbourne and Sutton & Cheam, and in practice this meant ten of the constituency polls had the Conservatives ahead – but these are just snapshot polls with margins of error, so many of these seats are in play. Note also, that many of the polls were last year and the Liberal Democrats have recovered slightly since then.

Looking at the LD-Lab battleground the average swing was a crushing 12 points from LD>Lab, meaning many of these seats are almost nailed on certainties for Labour. The exceptions are Birmingham Yardley, where John Hemming polled surprisingly well, Bermondsey where Simon Hughes was protected by a huge majority, Cambridge and Sheffield Hallam where Labour are coming from third and I expect the Lib Dems will benefit from tactical voting (Ashcroft showed Clegg behind in Hallam, but more recent ICM polling has him ahead). Hornsey and Wood Green is also interesting – the Lib Dem own polling has them doing better there and both the Lib Dems and Labour seem to be targetting it heavily, so it may be much more of a toss up than Ashcroft suggested.

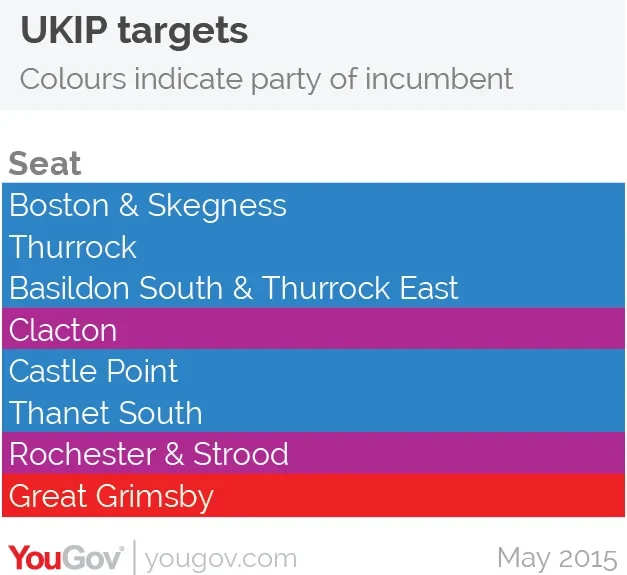

UKIP Targets

There is no easy way to come up with a list of UKIP targets – demographics, local and European election results can give us a steer, so can some of UKIP’s published statements about which seats they are targeting. Realistically though when a party has more than tripled their vote it is hard to accurately judge where their positions of strength and weakness are. The seats in the table are my best guesses of their most plausible gains (there are other seats where they have strength like Waveney, Great Yarmouth or Redcar that are in the Con-Lab battleground list… but I don’t think they stand much chance of actually winning any others, and constituency polling in some of those seats has shown them on the wane.

As to how they will do in these seats – I don’t think any are necessarily easy to call. Everyone assumes Douglas Carswell will hold Clacton given his margin of victory in the by-election, Mark Reckless in Rochester looks more vulnerable. Thurrock looks too close to call, as does Thanet South with its contradictory polling. Great Grimsby was a plausible UKIP gain, but recent polling has Labour with a healthy lead. Polling commissioned by UKIP donor Alan Bown gave them a stonking lead in Boston & Skegness last year, but this year an Ashcroft poll found the Tories ahead. My own guess is that Clacton will probably be a hold, and they have a chance in these other seats… but they won’t strike home in all of them.

And the rest

That leaves a few other interesting seats that don’t fit into any of the main battleground categories, but could change hands. Two are the seats held by smaller parties – I expect the Greens to hold on in Brighton Pavilion (but not gain anywhere else), how George Galloway will do in Bradford West is anyone’s guess. Watford appears to be the only Con-Lab-LD three way marginal that is still a three way marginal for the three parties – it could go either of the three ways.

PA image

This article first appeared on UK polling report