Uniform swing is now worse than useless – it is positively misleading

For some decades, uniform swing has been one of the most useful devices for making sense of British politics. Opinion polls measure votes; what matters at Westminster are seats. Uniform swing has traditionally been a fairly reliable way of converting votes into seats.

No longer. Uniform swing is now worse than useless. It is positively misleading. In particular, Labour can no longer hope to emerge as the largest party next May, even if it trails Conservatives significantly in votes.

In a sense, uniform swing has always seemed an odd concept. Formally, it assumes that the swing is identical in every constituency. We know that real life is not like that: swings vary from seat to seat. However, in most past elections, uniform swing projects have more-or-less worked because deviations from the average have broadly cancelled out. Seats that “should” change hands but don’t, because of below-average swings, have been offset by seats that “should not” change hands but do, because of above-average swings. In short, uniform swing has provided a good overall guide to the total number of seats even if it has been less reliable at predicting who will win each individual constituency.

The real statistical assumption underlying uniform swing, then, is not the obviously absurd notion that the swing in each seat is identical, but that deviations from the average are symmetrical. And that’s the problem: next year there are two big reasons why these deviations will not be symmetrical.

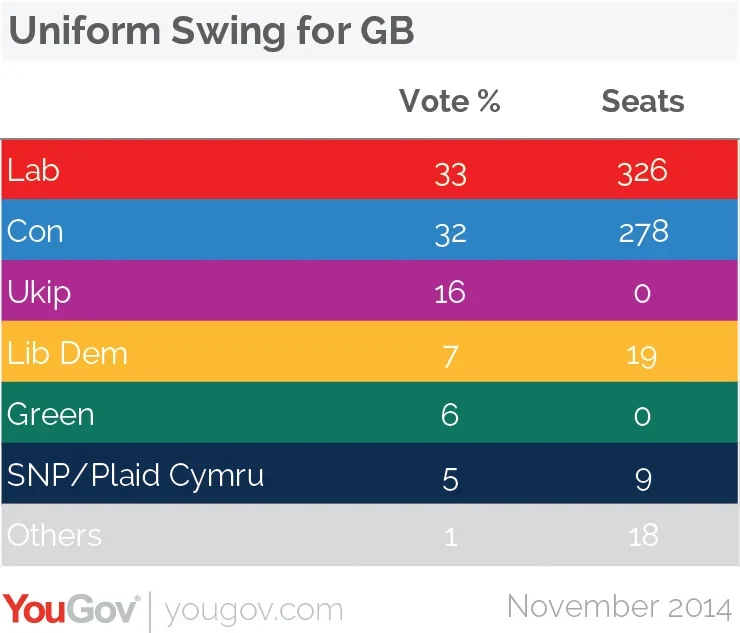

To see what might happen, let’s start with the recent average of YouGov voting intention surveys, putting Labour 1% ahead.* In 2010, the Conservatives won 37% of the vote, Labour 30% and the Lib Dems 24%. Compared with then, the Conservatives are down 5 points, Labour is up 3 and the Lib Dems are down 17. If we apply these changes to each constituency throughout Great Britain, this is what happens:

That projection looks good for Labour. Despite holding only a 1% lead in the popular vote, it ends up 48 seats ahead of the Conservatives and winning a narrow overall majority.

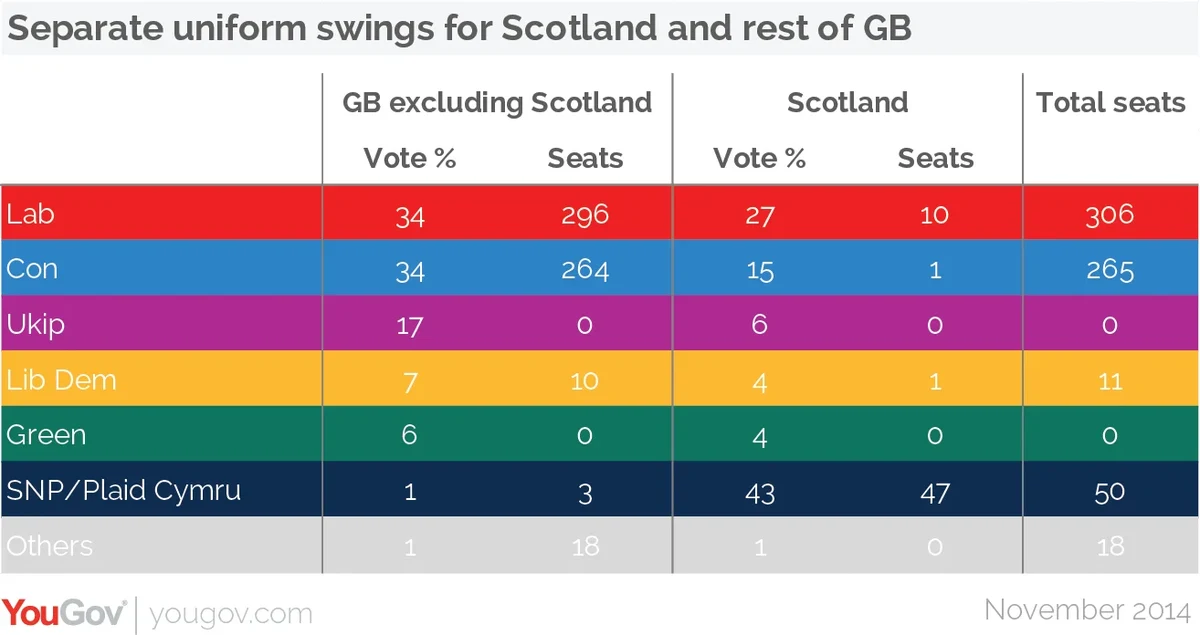

However, we now know that the SNP is currently thrashing Labour in Scotland. A recent YouGov poll for the Times showed the SNP 16 points ahead. That’s a far cry from the 22% lead that Labour enjoyed in 2010. At the very least, we need to apply two different projections, one for Scotland, and one for England and Wales.

The following table does this. In Scotland, it estimates the impact of the SNP’s advance at the expense of both Labour and the Liberal Democrats. It also takes account of the fact that, once we treat Scotland separately, the effect is to improve Labour’s standing in England and Wales. Instead of a 4% swing from Conservative to Labour across GB, we find a 5% swing in England and Wales. And as every Tory seat bar one is in England or Wales, this adjustment increases the number of Tory marginals that Labour could hope to gain (and, also, reduce fractionally the number of seats that the Tories regain from the Lib Dems).

However, Labour’s 11 extra gains south of the border are swamped by its 31 losses north of the border. The overall effect is to reduce Labour’s GB-wide total by 20 seats. It remains the largest party, but falls well short of a majority:

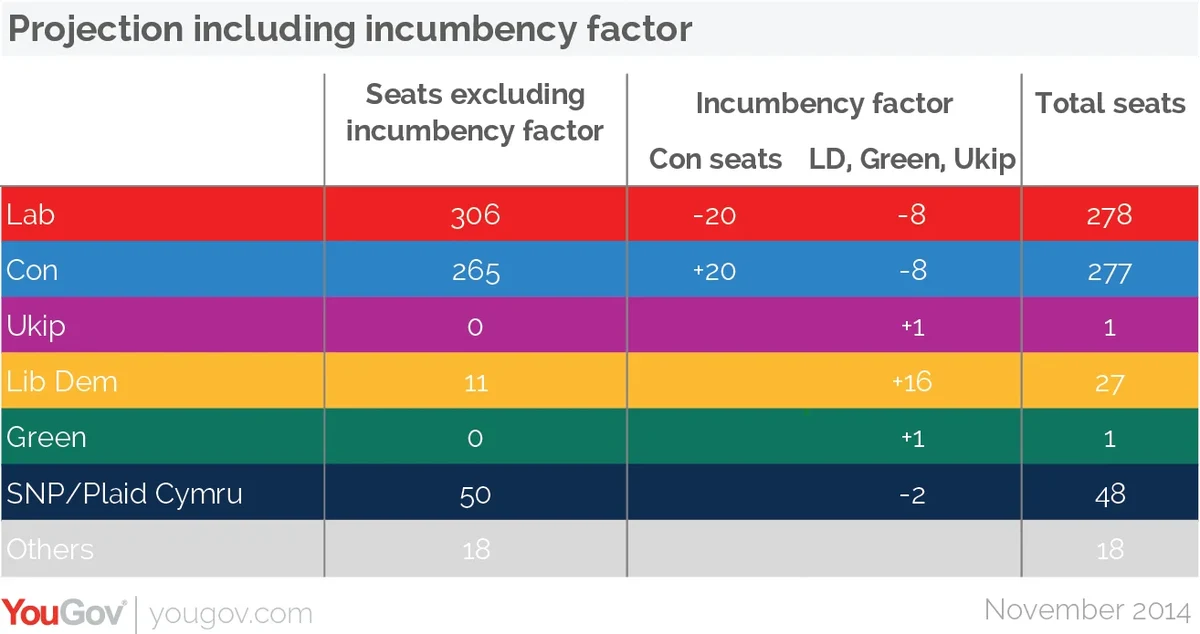

Now for the second way in which uniform swing is likely to break down. For the past three decades, there has been a consistent trend for new MPs to do slightly better than the average, the first time they seek re-election. On average, the bonus is worth 2%. On YouGov’s current figures, showing a 5% swing across England and Wales, this means that Tory MPs who were first elected in 2010 would expect, on average to suffer an adverse swing of just 3%.

This applies to virtually all the Tory seats that Labour hopes to gain, for Conservative marginal are precisely the seats where Labour was turfed out last time. New Tory MPs have been able to dig themselves in and become better known locally. A handful of Tory MPs in marginal seats are standing down; the incumbency bonus won’t apply to these. But, for the rest, it seems likely that the average swing in the seats that Labour really needs to win will fall short of the national swing. Assuming a 2% differential, in line with the historic average, this would allow the Tories to hold on to around 20 seats they would otherwise lose.

Lib Dem MPs are also likely to enjoy an incumbency bonus, though the scale of it is harder to predict at this stage. The table below inevitably involves some guesswork: readers may choose to substitute their own judgement. I also assume the Douglas Carswell will hold Clacton for Ukip and Caroline Lucas holds Brighton pavilion for the Greens.

On these figures, Labour and the Tories end up neck-and-neck in terms of both votes and seats. The basic bias in Labour’s favour in Britain’s electoral geography is wiped out by the combined impact of Scotland and the incumbency factor.

Things may – indeed, things WILL – change between now and next May. This analysis takes no account of possible Ukip gains. Nor does it allow for the way the parties will fight the marginals: will Labour win the “ground war” and reduce the Tories’ incumbency bonus? Will the Tories manage to squeeze Ukip support in Con-Lab contests with their message, “vote Farage, get Miliband”? Will Labour recover in Scotland? Above all, will the underlying support for each party change over the next five months – and, if so, how far and in what direction?

All that said, the overall conclusion is clear: Britain-wide uniform swing projections won’t work this time; and, unless the total votes won by Labour and the Conservatives are extremely close, it is pretty certain that the party with the more votes will end up with the more seats. Labour can forget dreams of ending up the largest party even if it wins a million fewer votes than the Tories.

* Throughout this blog, vote shares exclude Northern Ireland (in common with normal polling practice) but seat projections include the 18 seats allocated to the province.