Most people in Britain approve of paid surrogate pregnancies – but public support is lower when it is used by gay couples

Recently an Australian couple were accused of abandoning a child with Down’s syndrome and a heart condition with his surrogate mother in Thailand, while taking home to Australia the child’s healthy twin sister. The details of the case are murky – the surrogacy agent who arranged the deal claims the couple later offered to take the child – but the incident shed light on the issue of regulation in surrogacy.

Surrogacy itself, or the process of a “surrogate” mother carrying a child for someone else, has been regulated under British law since the 1980s. In 1985, the Surrogacy Arrangements Act made commercial surrogacy – when the surrogate is paid a fee – prohibited, so surrogates in the UK must currently be volunteers (though they can be paid for reasonable expenses related to the surrogacy).

New YouGov research finds that the law is out of sync with British public opinion on this issue.

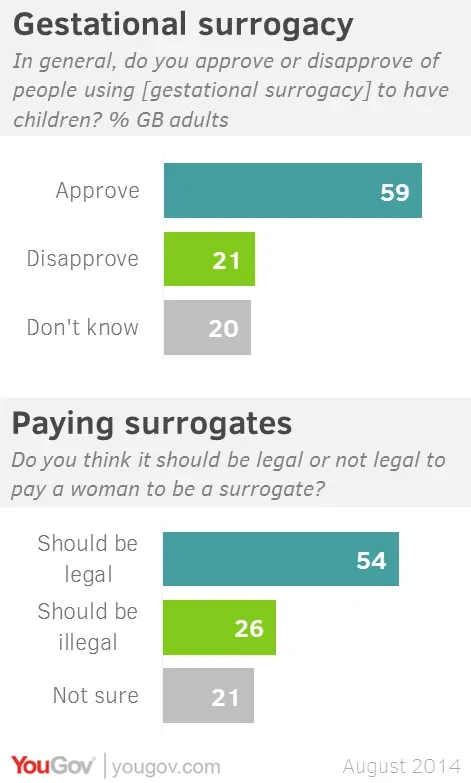

59% of British adults now approve of the process called 'gestational' surrogacy: when a woman carries another couple’s fertilised embryo in her womb from pregnancy to birth, even though she has no biological connection to the child. 21% disapprove people using this process to have children.

By a slightly narrower margin, 54% to 26%, the British public also support making it legal to pay a surrogate. In both cases, support is higher among younger adults, although people who are positive about surrogacy outweigh the detractors across all age groups.

There is no ban on commercial surrogacy in the United States, at least on the federal level, and states like California and Illinois both permit and facilitate surrogacy arrangements. Other states do not recognise these arrangements or prohibit them.

By 69% to 16% Americans approve of couples using gestational surrogacy, and by a near-identical margin (69% to 15%) say it should be legal to pay a surrogate.

Surrogacy and sexual orientation

A recent headline in the Daily Mail newspaper caused controversy when it described a proposed NHS sperm bank – a key resource for some couples when pursuing surrogacy – as “for lesbians”, though it technically made its services available to all women and couples, gay or straight.

The incident underscores how social sensitivities can complicate the debate over processes like IVF and surrogacy.

Indeed, YouGov’s research finds that there is lower support for surrogacy when it involves a gay couple seeking a surrogate rather than a heterosexual couple. In fact, telling respondents the couple using surrogacy is gay lowers approval of the process much more than telling respondents the couple is paying their surrogate (see chart).

To test this, YouGov asked half of respondents two questions about a “married gay male couple” using surrogacy – one question asked about the use of a paid surrogate and one asked about a volunteer surrogate. The other half of respondents were asked the same two questions, but about a “married heterosexual couple”.

When the couple is straight, most British people approve of the surrogacy arrangement, whether it is paid or voluntary (though support is 8 points lower for the paid arrangement). When the couple is gay, support falls around 15 points for both arrangements.

Here, the age of the respondent becomes much more consequential: Adults over 40 tend to approve of the straight arrangements and tend to disapprove of the gay arrangements. On the other hand, by wide margins, under-40s approve of the surrogacy arrangements in all four scenarios, with only slightly lower approval in the case of the gay couple.

In the United States, the overall effect is even more dramatic: Americans are more approving than British people when it comes to the heterosexual couple, and divided on the gay couple in proportions virtually identical to those found in Britain.