Older people, who are more likely to want Britain to leave the EU, are also more likely to vote

This article first appeared in the Guardian

The consensus view on the forthcoming EU referendum is that it’s all going to be fine. The British are a cautious lot, goes the thinking, and in the end they’ll heed the prime minister’s warnings about taking ‘a leap in the dark’ and stick with the status quo.

The backdrop to this consensus view is the fresh memory of two elections – the recent general election and the Scottish independence referendum. In both cases, despite much hysteria and talk of nail-biting finishes, the dull-but-sensible option handily won the day. Why should this test, the third in a row, buck the trend?

The polling evidence seems to support this view. Recent polls conducted online tend to show the race neck and neck, while polls conducted by telephone show a substantial lead for staying in of around 15 points. The latter number suits the gut narrative better, and even my esteemed colleagues Stephan Shakespeare and Anthony Wells prefaced yesterday’s YouGov poll for the Times (which showed the ‘Leave’ campaign one point ahead) with the guidance that ‘remain has notable advantages and we would expect the number to end up moving towards remain’.

But while it is obviously true that certain fundamentals favour the ‘remain’ campaign - risk aversion, the might of the media-political establishment – there is one fundamental that has the power to trump them all and that seems to favour the Brexiteers: turnout.

Turnout will decide this referendum. It’s not about how the country divides when talking to a pollster from the comfort of their living room. It’s about who cares enough about this issue to go and vote.

The single most important driver of turnout is age. Put simply: most old people vote, most young people don’t, and so old people usually get their way in elections. In both the Scottish referendum and the recent general election, older people strongly favoured the ‘no’ campaign and the Conservatives respectively. The young flag-waving ScotNats and Milifans lost out to their more conservative parents and grandparents.

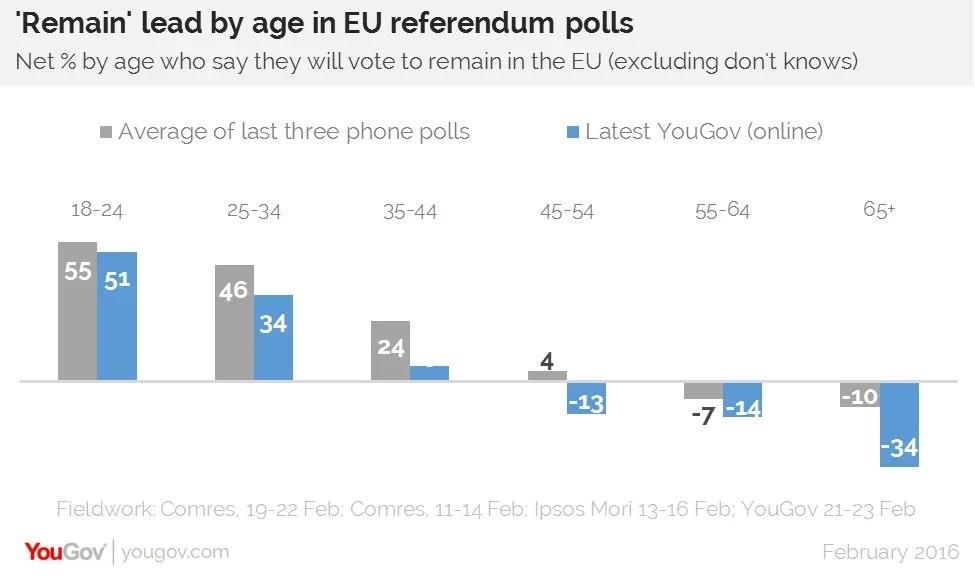

This time it’s the other way round: in every poll taken this year, whether by phone or online, the oldest generations want out of the EU, while the youngest generations are overwhelmingly in favour of staying. We’re in the strange situation where the older generations are crying out for change and young people are sensibly arguing for the status quo.

Under-estimating the effect of the age-skew in turnout is thought to be a large part of why pollsters got the last general election wrong. Because there were too many politically engaged young people in the survey samples, and young people are more left-leaning, pollsters’ models were built on the expectation that more of them would vote than actually did.

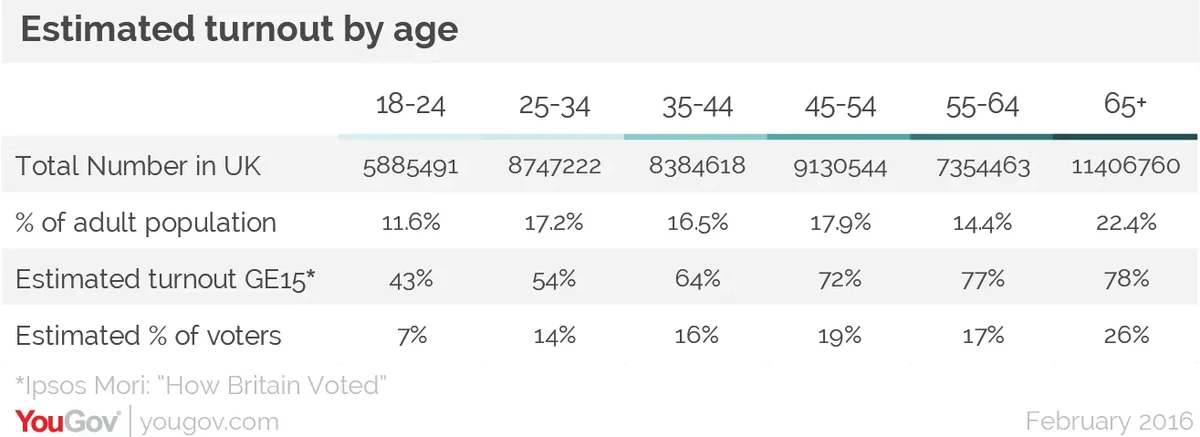

Although we’ll never know precisely how the different generations voted in 2015, best estimates suggest that around 43% of 18-24 year olds voted compared to around 78% of over 65s. With 6m 18-24 year olds in the UK and over 11 million over 65s that means that the over 65s carry more than three and a half times more weight than the youngest cohort.

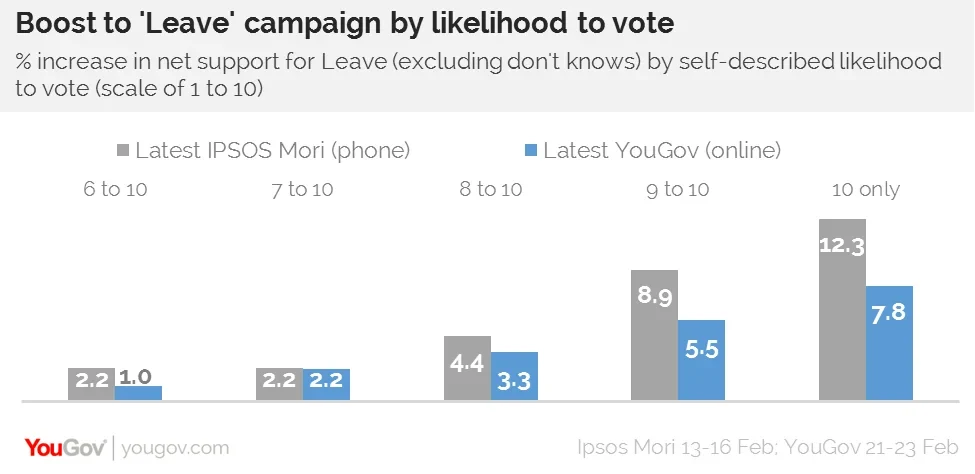

In the EU referendum, turnout will not just be about age. There are other factors such as social class and education that potentially help the ‘remain’ campaign. But overall there is no doubt that the people most determined to vote are the Brexiteers. The polls agree about this, no matter where they put the overall state of play. In the latest YouGov poll, conducted online, the result among people ‘absolutely certain’ to vote tilts seven points more favourable for leaving the EU (+7 compared to +1); in the latest Ipsos Mori poll, conducted by phone, the result tilts eleven points more favourable among the same group (-7 compared to -18).

It’s not hard to see why. The country is overwhelmingly Eurosceptic – every survey from every source confirms that the European Union is a widely and deeply unpopular institution. As a rallying cry, ‘vote to stay part of a club none of us particularly like because, reluctantly, it’s the sensible option’ is plainly less exciting than the alternative. ‘Hope’ and ‘Change’, those atmospherics that always gather to one side or the other in elections, seem naturally to be the property of the ‘Out’ campaign.

With this in mind, you could treat the contrasting numbers coming out of the telephone and internet pollsters as useful proxies for a high-turnout and lower-turnout referendum result. The phone pollsters don’t offer a ‘don’t know’ option up front, and so push around 90% of respondents into choosing a side. As we know, the less people care about it, the more they naturally favour the status quo, so you end up with a healthy lead for ‘remain’. But the UK has never in its history had an election with 90% turnout; around 30% of those people will not vote.

Meanwhile, online pollsters like YouGov offer four options to click on – ‘remain’, ‘leave’, ‘will not vote’ and ‘don’t know’ – and around 25% of people choose one of these last two options. The headline numbers are therefore from people who have made up their minds. So we may actually have two ‘accurate’ estimates – the phone pollsters measuring the whole population when prompted to choose, the online pollsters closer to a measurement of the voting public.

The polls showing broad leads for ‘remain’ are only helpful to the ‘leave’ campaign. The more certain people are that ‘remain’ will win, the more complacent the mood, the less compelled they will feel to vote. The difference between success and failure for David Cameron and the ‘remain’ campaign may be whether they can get their natural supporters – the busy, the young, the centrists of England – committed enough to make their way to a polling station when the sun is shining this Midsummers Day.

PA image