David Cameron is on course to lead the largest party following May’s general election – but it could be touch and go whether he can remain prime minister

This prediction takes account of both recent YouGov polling data and the lessons from history about how public opinion moves in the final weeks before general elections. I shall update my forecast at regular intervals between now and May. No prediction can ever allow for outside shocks, unexpected scandals or one party running a far more effective campaign than its rivals. Like economic forecasts, political predictions need to adapt to fresh information.

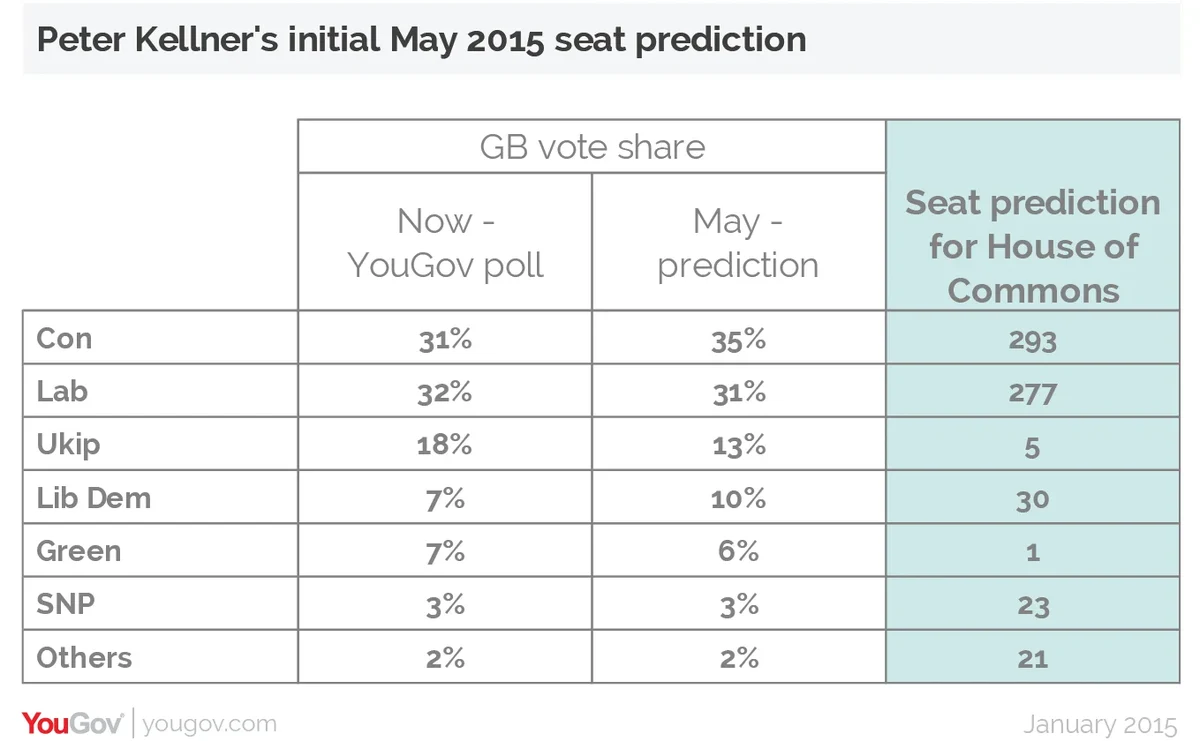

At present, Labour leads the Tories by one point. Last week’s disputes over the economy, NHS and TV debates have had little effect. All ten of our January polls have found the two parties neck-and-neck, with Labour on 33% plus or minus one, and the Conservatives on 32%, again plus or minus one.

All polls are snapshots. To convert them into a forecast of who will win in May, we must do two things: judge how votes overall will shift overt the next 16 weeks, and then translate the predicted vote shares into seats in the new House of Commons.

For shifts in vote share, my starting point is what happened the last time the Conservatives were in power. In each of the four elections from 1983 to 1997, the final four months saw a 2-3% swing back from Labour to the Tories. (For the technically-minded, these figures allow for the Labour bias in the polls in 1992 and 1997.) I assume a similar swing this time. This converts today’s near-equal shares into a Conservative lead of 4%.

The Conservatives may end up with a bigger lead, if the Liberal Democrats attract back more votes than I expect of those they have lost to Labour since 2010, and the Tories do better in winning back votes they have lost to Ukip.

As for converting votes into seats, first-time MPs tend to do better than average when they defend their seats. Virtually all the Conservative-held marginals are being defended by MPs who gained their seats (mainly from Labour) in 2010.

My forecast implies a swing from Tory to Labour in England and Wales of 2.5% since 2010. On a uniform swing this would produce 31 Labour gains (in addition to Corby, which Labour captured in a by-election.) My current judgement is that the incumbency bonus is worth around 12 seats to the Tories – seats that they will hold on below-average swings.

My initial prediction assumes that Lib Dem MPs will also enjoy an incumbency bonus, and hold on to 30 of the 57 seats they won last time. Without this bonus they would struggle to retain 20 seats. As for Ukip, I expect Douglas Carswell to hold Clacton but Mark Reckless, the other Ukip by-election winner, is likely to lose his. Currently, Ukip is likely to win another four seats; but this figure could well change, depending on whether local voters in their key target seats can be persuaded that Ukip has a real chance of victory locally.

Scotland presents a real conundrum. SNP remains well ahead of Labour. If its lead holds up to polling day, the party could crush both Labour and the Lib Dems north of the border. I assume some move back to Labour, and – as in England – Lib Dems MPs standing for re-election to enjoy an incumbency bonus. For the moment, I expect the SNP to gain 17 seats, to take their total to 23. But a high proportion of Scottish seats are likely to produce tiny majorities: a small variation in votes could result in a significant shift in seats from my central forecast.

If my predictions are precisely right, then the outcome will be far messier than last time. The Conservatives, with 293 seats, will be 33 short of the 326 needed for an overall majority. If they join forces with the Lib Dems, they get to 323 – still three short, although theoretically just enough if Sinn Fein, likely to hold their five seats, continue to boycott Parliament. Support from the Democratic Unionists’ eight or nine MPs would allow Cameron to govern fairly comfortably – as long as right-wing, Euro-sceptic MPs don’t make trouble.

Alternatively, if the Lib Dems decide to switch sides and back a Labour-led administration, and Ed Miliband can strike a deal with the SNP and Northern Ireland’s SDLP, then he could enjoy an overall majority of 16.

These calculations illustrate a wider point. Small differences in seat numbers can have a huge political effect. Suppose this prediction is just ten seats out for the two big parties. If the result is Con 303, Lab 267, then some kind of Conservative-led government is far more likely. But if the result is Lab 287, Con 283, then Cameron will have little choice but to resign as Prime Minister and, in all probability, step down as Conservative Party leader.

An edited version of this commentary was first published in the Sunday Times