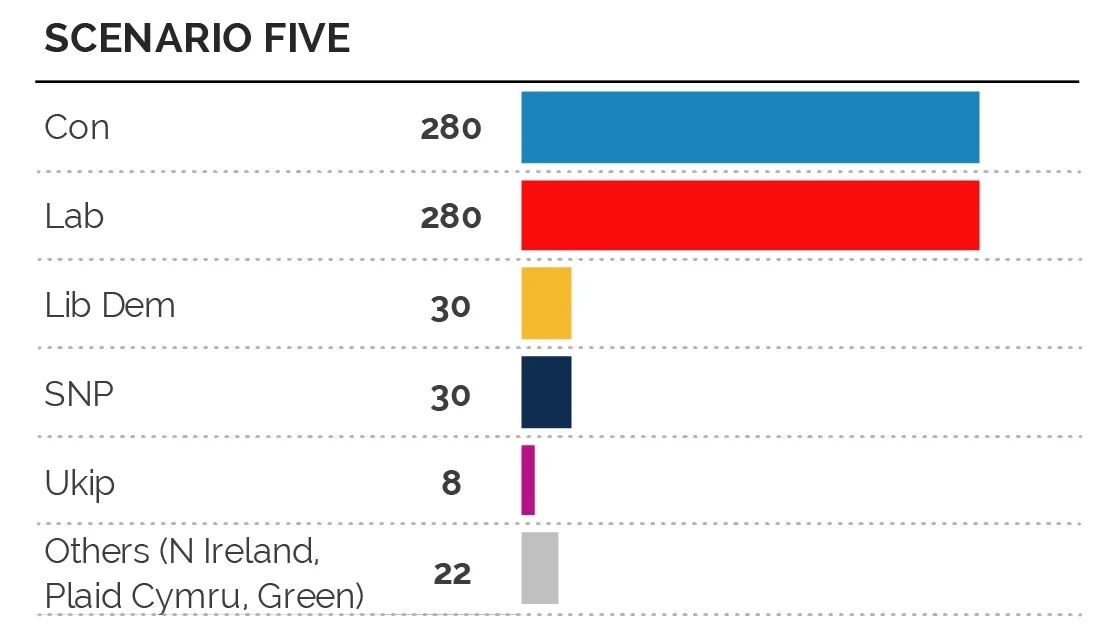

The polls suggest neither Labour nor the Conservatives will win an overall majority. Here are five possible scenarios

Recent YouGov polls have suggested that next May neither Labour nor the Conservatives will win an overall majority. On May 8, after the votes have been counted, the issue may well be what kind of hung parliament will Britain have? There are many different forms, and the rise of Ukip and the Scottish National Party, and the decline of the Liberal Democrats, have sharply increased the range of possible outcomes. Here are five possible scenarios, and five quite different trajectories for British politics in the years ahead.

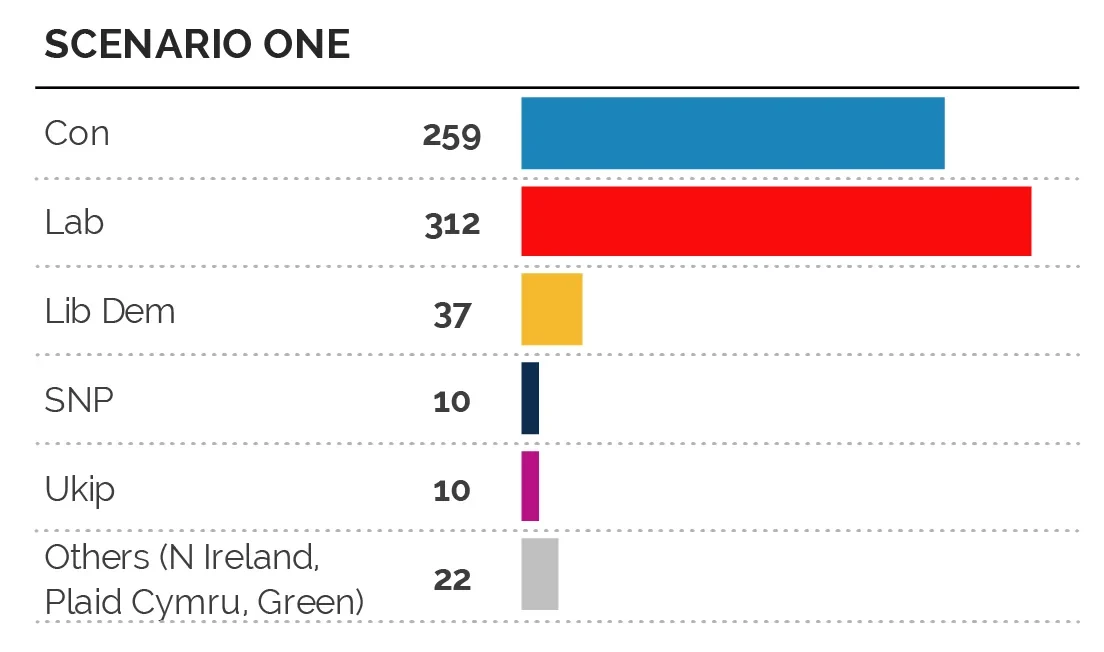

Ed Miliband will have a few hours to savour his moment of near-triumph. Labour will be 14 seats short of an overall majority, but it will have captured more than 40 seats from the Conservatives and a dozen from the Lib Dems, and successfully defended its Scottish citadels from the SNP. David Cameron, who will have seen Tory seats tumble to Ukip as well as Labour, will have no choice but to resign as Prime Minister and advise the Queen to invite Miliband to form a government.

But what kind of government? Miliband might be tempted to run a one-party minority administration. He can probably count on the support of three SDLP MPs from Northern Ireland. This takes his tally to 315. And if Sinn Fein again has five MPs who don’t take their seats at Westminster, then he would be only eight seats short of the 323 he would need for an effective overall majority of one.

For such a government would be defeated, the Tories and virtually all the minority party MPs would have to join forces. Miliband could probably strike a deal with a disappointed SNP on further powers for Scotland. If he does, he would have a free hand to implement the rest of Labour’s manifesto.

On the other hand, he may calculate that a wider agreement with the Lib Dems would give him a comfortable overall majority of 48 – enough for five years of stable government without having to worry about defections or by-election defeats. Whether Nick Clegg (assuming he still leads his party) and his colleagues are up for a deal – either in the form of a full coalition or a looser confidence-and-supply arrangement – is another matter, which might not be resolved for some days.

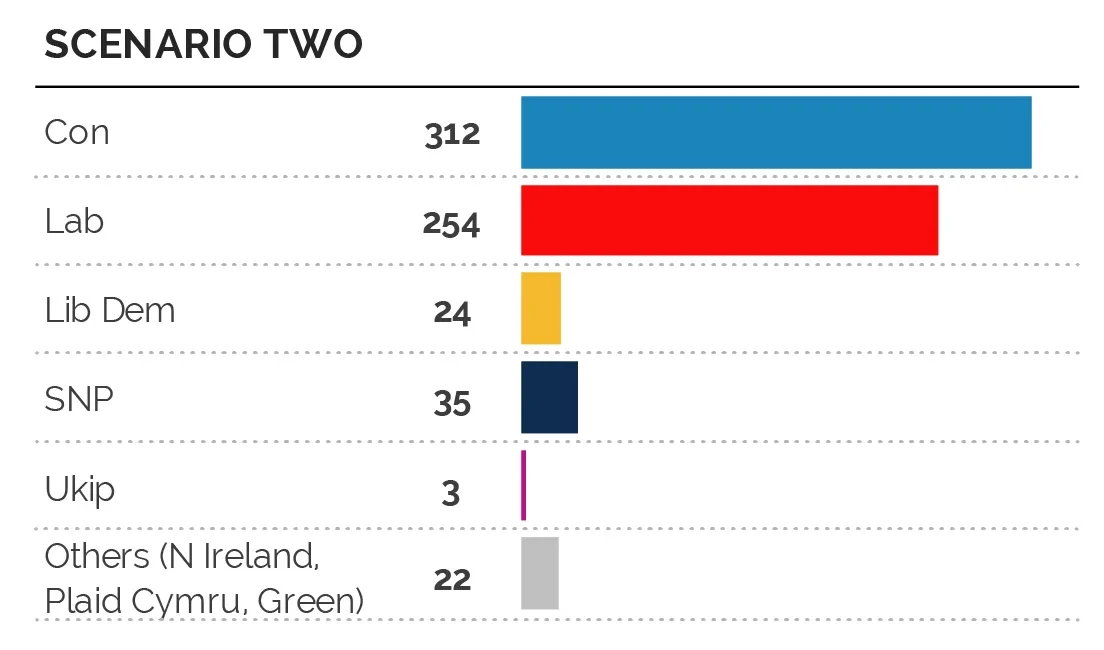

This time, Cameron holds the stronger hand. The Conservatives have gained more seats from the Lib Dems than they have lost to Labour. Ukip has been beaten back. Labour has suffered badly in Scotland.

The chances of another Conservative-Lib Dem coalition are slim. Even if Cameron and Clegg wanted to renew it, their parties would probably not. The Prime Minister’s favoured option is likely to be a deal with the 8-10 Democratic Unionist MPs from Northern Ireland.

Under this scenario, Cameron has another advantage. In the past, SNP MPs have voted only on issues that directly affect Scotland. If they maintain this practice, and their 35 MPs abstain on non-Scottish matters, then the Conservatives would have a secure majority for much of their domestic agenda.

All in all, Mr Cameron has a real chance of another five years in office – if, and it’s a huge ‘if’ – he can keep his anti-EU backbenchers in line. But if those backbenchers start to make trouble, the Prime Minister may need to work occasionally with some combination of Lib Dem, SNP and even Labour MPs to assemble issue-by-issue majorities in Parliament, not least on the vexed matter of Britain’s membership of the European Union.

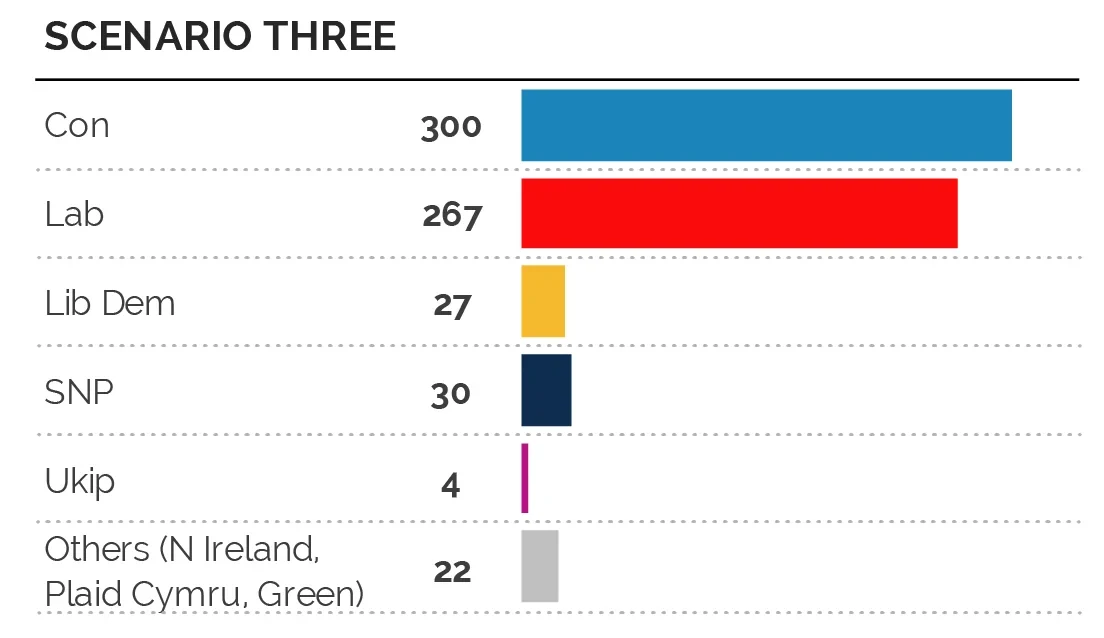

Scenario three is far trickier for Cameron. The Conservatives have lost seats but remain comfortably the largest party. As the incumbent Prime Minister, he has the perfect right, perhaps even duty, to remain in office and seek to construct a majority – initially for the programme outlined in his post-election Queen’s Speech.

However, to do this, it won’t be enough just to get the DUP on board. He will lose any vote in which Labour, the Lib Dems and SNP join forces against him. He must make sure that doesn’t happen, either by doing an overall deal with one of them, or devising divide-and-rule tactics issue by issue.

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s new First Minister, has said the SNP will never do a deal with the Tories. However, if Mr Cameron remains Prime Minister, Sturgeon will have to talk to him about Scotland’s future. An overall Con-SNP deal may be out of the question, but vote-by-vote arrangements might still be possible.

However, keeping the show on the road for a full five years may be impossible. Labour and the SNP are certain to oppose Cameron’s plans for a referendum on whether Britain should leave the EU. If the Lib Dems also vote against a referendum bill, then Cameron will be defeated. He could well then call, and possibly lose, a vote of confidence, which would pave the way for an early general election.

On the other hand, if the Lib Dems fear losing even more seats, they might support, or abstain on, a referendum bill. This would allow it to pass, and for Mr Cameron to carry on.

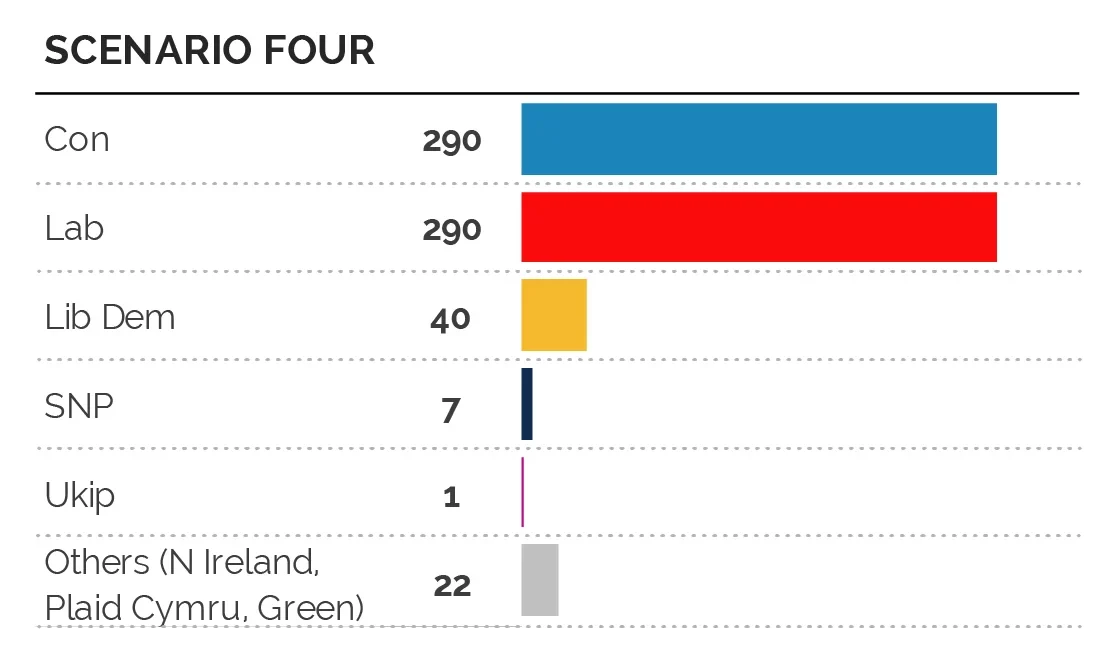

This scenario poses a different kind of dilemma for the Lib Dems. They will still be a major force at Westminster, unlike Ukip and the SNP, which will have seen their fortunes fade in the weeks leading up to the election. Mr Clegg has a genuine balance of power. He is able to deliver a majority to either Labour or the Conservatives.

What he won’t have is the option that many of his activists might prefer, of going into opposition in order to revive their radical credentials unsullied by the inevitable compromises of office. The public – and the financial markets – are unlikely to look kindly on a party that plunges Britain into an era of instability by refusing to do any kind of deal with either Labour or the Conservatives. The Lib Dems would be in the position of a vegetarian forced to choose beef or lamb – and not being allowed to reject both.

However, it may be some days before the shape of the new government becomes clear. Again, as the incumbent Prime Minister, Cameron could have the first go at assembling a parliamentary majority – provided that Conservative MPs don’t eject him first. Tory backbenchers may decide that he has blown his chance to win the election and think they have a better chance in future under someone else – Boris Johnson? Theresa May? A. N. Other?

However, if Cameron, having lost the confidence of his MPs, resigns as Prime Minister, it is a moot point whether the Queen will invite Miliband or the new Conservative leader to form a government. In order to avoid dragging Her Majesty into controversy, there will be intense pressure at Westminster to assemble a stable majority, and so make the Queen’s decision straightforward. Again, the Lib Dems will be forced in practice to abandon the luxury of a spell in opposition.

Welcome to Borgen Britain. As in the Danish TV drama, the challenge will be to construct a multi-party government. In scenario four, the Lib Dems could deliver a majority to either Labour or the Conservatives. This time they can do neither. Either a Con-Lib Dem or a Lab-Lib Dem government would fall 16 seats short of a majority (or 13 seats short if Sinn Fein MPs continue to stay away from Westminster).

But if the arithmetic suggests symmetry, the politics do not. The Conservatives will have lost. Cameron would need the support of the Lib Dems, the SNP and his own backbenchers in order to carry on. The chances of getting any of the three are slim – and of getting all three, beyond remote.

The likeliest outcome is some kind of Labour-led government. The party will have done well in England, albeit badly in Scotland. If Miliband can strike some kind of deal with the Lib Dems and SNP, he will have the support of 340 MPs and a majority of 30. If we add in three SDLP MPs from Ulster, and again assume the non-participation of five Sinn Fein MPs, then the majority rises to 41.

The challenge will be to secure an arrangement that lasts five years. A formal three-party coalition would mean SNP ministers at Westminster – presumably running the Scottish Office. That looks improbable. Miliband and Clegg might be attracted by a two-party Lab-Lib Dem coalition, with the SNP supporting the government from the opposition benches. Tricky, but not impossible.

Whatever arrangement is made, it is likely to feel temporary rather than permanent. Miliband may want a year or so in office to persuade voters that he is up to the job of Prime Minister – something he has signally failed to do in the past four years – and then find a way to seek a more secure mandate. Get ready for a second general election in 2016.

An edited version of this commentary appears in today’s Times