David Cameron has six months in which to stop Ukip’s bandwagon. If he fails, the Conservatives risk not only losing next year’s general election but suffering lasting damage.

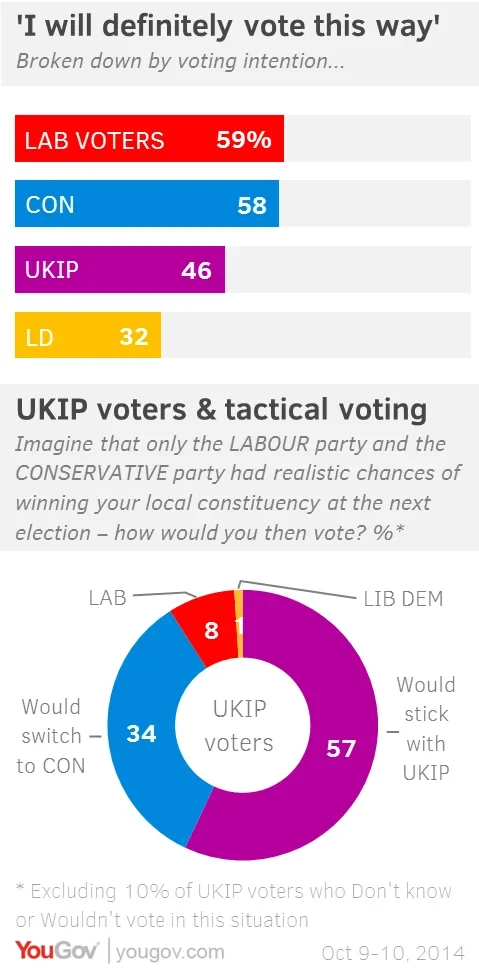

YouGov’s latest Sunday Times survey demonstrates both the opportunities and the dangers that confront the Tories following last week’s by-elections. For the moment, Ukip’s vote is softer than that of either Conservative or Labour. Six out of ten supporters of the two main parties say they have definitely made up their mind how to vote next May. Among those who currently back Ukip, just 46% are equally certain.

Our poll also finds that Cameron’s warning to Ukip supporters in the key Conservative-Labour marginals – vote Farage, get Miliband – could have some effect. When Ukip supporters are asked how they would vote if only Labour or the Tories had a realistic chance of winning locally, as many as 34% say they would return to the Conservatives. Just 8% would vote Labour. If Ukip’s vote in these seats is squeezed in this way, the Conservatives will hold up to 20 seats they otherwise stand to lose to Labour.

But if the Tories fail to squeeze Ukip’s support sufficiently in these seats, their longer term outlook is bleak. For Ukip represents a very different, and potentially more enduring, kind of protest vote from that harvested in the past by the Liberal Democrats.

The typical Lib Dem voter in its glory days was a graduate under 40 with a decent job. She was comfortable with the modern world and disdained mainstream politicians for not adjusting to it fast enough. Such voters helped the Lib Dems to win spectacular by-election victories mainly in well-off towns and suburbs.

The typical Ukip voter is very different. YouGov analysis of more than 40,000 people we have polled in recent weeks finds that Ukip support is highest among men over 60 (23% of whom support Ukip) and people who left school at 15 or 16 (22%). Their lowest support is among graduates and women under 40 (both 7%).

All this helps to explain why Ukip did so well in Clacton, one of the belt of seats east of London where people are older and poorer than the national average. Many feel that the modern world has left them behind. They want to return to the days when Britain was quieter, whiter, more predictable and less European.

Today’s Ukip supporters are far angrier than the voters who fuelled Lib Dem victories in the past. Electorally, anger is a harder emotion to quell than disdain.

However, Nigel Farage is wrong to claim that he poses an equal threat to both Labour and the Conservatives, at least in the short term. For the most part, Ukip’s strongest support is in Conservative areas.

This is because UKIP attracts three ex-Tories for every ex-Labour voter. Of those who voted in the 2010 general election, 47 per cent voted Conservative, while just 14 per cent voted Labour. (As many as 19 per cent voted Lib Dem.) In economic and social terms, Ukip might be expected to attract former Labour supporters. But when it comes to values, Ukip’s supporters are well to the Right.

True, the party has won some impressive second places in northern Labour seats in by-elections, most notably in winning 39% in Heywood and Middleton on Thursday. But it did this mainly by taking votes off the Tories and Lib Dems.

Together, the two coalition parties won 50% there in 2010. On Thursday their combined share was just 17%. Labour’s share actually went up slightly. Admittedly, without Ukip’s intervention, Labour’s support would have risen more. But the Heywood and Middleton result does not indicate any of Labour’s northern strongholds falling to Ukip next May. The only seat that looks vulnerable is Rotherham, where Ukip won more than 40% of the vote in this year’s European Parliament elections. Otherwise, the best Ukip can hope for in the North is to establish itself as the main challenger to Labour next May, and to start winning seats there in 2020.

One other Labour seat where Ukip ‘won’ in the Euro elections was Grimsby, where Austin Mitchell is standing down. Every other seat among the top dozen Ukip prospects is currently held by the Conservatives, although Thurrock is one where Labour starts only 92 votes behind the Tories.

These calculations, like much of the discussion since last Thursday, relate to next year’s election. But Ukip’s successes this year could have a more fundamental impact on the character of British politics.

Ever since the modern Conservative Party was formed by Sir Robert Peel in the 1830s, it has succeeded by harnessing two great causes: enterprise and patriotism. It has been the party of business, commerce and trade, instinctively internationalist; but is has also been the party of nation, tradition and the union flag.

Occasionally these two great causes conflict, and the Tories are ejected from power. It happened over the Corn Laws in the 1840s, tariff reform 110 years ago and Europe in the 1990s. But each time the party eventually reconciled the two causes and returned to office.

Now, with Ukip’s surge of support, there is a real possibility that the two causes will be advanced by two separate parties: a Conservative Party that wants to stay in a reformed European Union, and Ukip, which wants a completely different relationship with the rest of the world: fewer immigrants, no overseas aid and outside the EU.

Under our first-past-the-post system for electing MPs, such a division within Britain’s Right could well help Labour, not just next May but for years to come – just as the defection of almost 30 Labour MPs to the new Social Democratic Party thirty years ago helped the Conservatives to remain in power through the Eighties.

No wonder Mr Cameron hopes that Clacton will join the long list of by-elections that look seismic at the time but eventually leave the political landscape unchanged. It’s not just his prospects next May that depend on it, but the long-term future of his party.

This blog is adapted from weekend commentaries for The Times and Sunday Times