What's going to happen if Labour and the Conservatives are neck-and-neck in May?

The general election is now just over eight months away. None of us can be sure what will happen. What we can do, however, is explore the main factors likely to determine the outcome. This kit allows readers to select the factors they think will apply, and to assess their impact on the overall result.

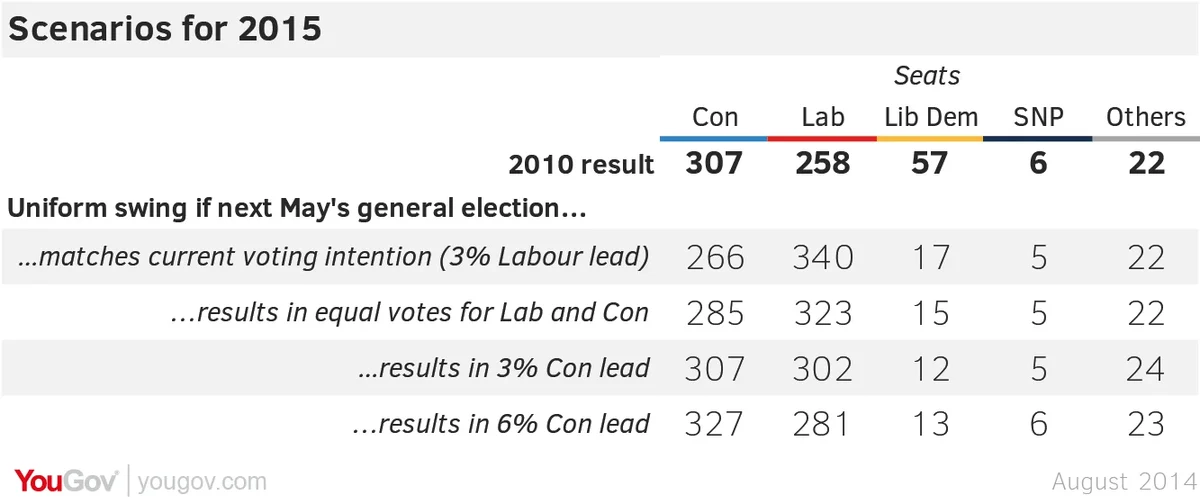

The first table shows the main figures. I start with four scenarios: The first of these assumes that people will vote in line with the average of recent YouGov polls: Labour 37%, Conservative 34%, Ukip 12%, Liberal Democrat 8%. Compared with 2010, this means that Labour would be up 7 points, the Tories down 3, Ukip up 9, Lib Dems down 16. I have applied these changes to every constituency. (Actually all bar one: I assume the Greens’ MP, Caroline Lucas will successfully defend her 1,252 majority over Labour.) The result is that Labour would end up with 340 seats, an overall majority of 30.

In the past, Conservative governments have recovered ground in the months leading up to elections. I show three alternative “recovery” scenarios: 36% each for Labour and Conservative, a 37-34% Tory lead and a 39-33% lead. I have left Ukip and Lib Dem support unchanged.

However, I would be surprised if uniform swing will work as well next year as in the past; and I doubt whether UKIP and the Lib Dems will end up on their present levels. In the following table I set out six different factors and how they might affect any uniform-swing calculation. Equal votes would leave Labour just three seats short of an overall majority, and 38 ahead of the Tories. A three-point Conservative lead would leave the two main parties virtually level-pegging in seats. A six point Tory lead would give the party 327 MPs and an overall majority of four.

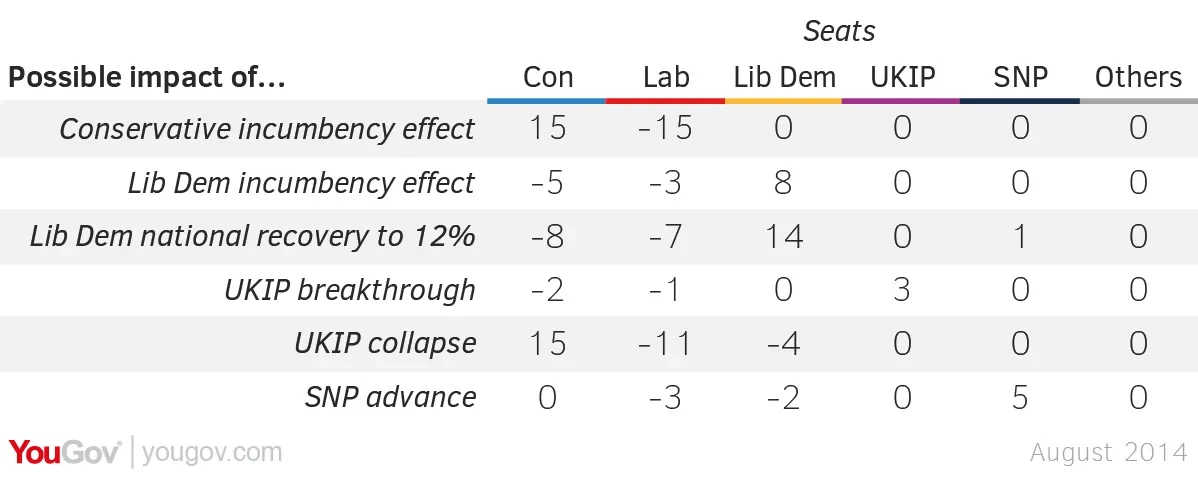

Second, it is likely that most Lib Dem MPs defending their seats will lose fewer votes than Lib Dem candidates elsewhere. The size of this effect is more of a guess; I assume that eight Lib Dem MPs will hold seats they would otherwise lose, five against Conservative challenges, three against Labour. First, I expect the swing against the 2010 intake of Conservative MPs to be less than the national average. This incumbency bonus has applied at every election for the past 30 years. If that pattern persists, the Tories may well hold around 15 seats they would otherwise expect to lose to Labour. (The incumbency effect would be far less if the Tories recovery to a 6% national lead, as they would lose few seats on a uniform national swing.)

A bigger impact would come from a lib Dem national recovery. Until recently I expected them to end up with around 15% support. Following dire local and European election results and continuing terrible poll ratings, I have downgraded my expectation to 12%. This four-point rise from today’s poll rating would still save them an extra 14 seats. If they benefit from the incumbency effect as well, 12% would give them 22 seats more than their current 8%, uniform swing estimate.

As for Ukip, I show two scenarios. The first is that they pick up three seats they are targeting, following local success in this year’s local and European elections: Thanet South and Great Yarmouth from the Tories and Grimsby from Labour. Alternatively, their support might fall, as voters turn from protest mode to choice of government. This effect is likeliest to be strongest in Tory marginals, as local voters are bombarded with the message, “vote Farage, get Miliband”. Voters deserting Ukip in these seats are likely to switch mainly, but not exclusively, to the Conservatives. I make the cautious assumption that the net effect will be equivalent to an extra 1% swing to the Tories in these seats – enough to win them an extra 15 MPs. (As a rule of thumb, if you double the net swing to 2%, you can roughly double the impact in seats.)

Finally, if the SNP, recovering from its likely defeat in next month’s referendum, persuade a number of Scots to “vote SNP in order to extract extra ‘devo-max’ powers from London”, they might pick up an extra five seats: three from Labour and two from the Lib Dems.

Combining these factors is a matter of judgement. A Labour optimist would hope that the party maintains its current lead and, by dint of effective ground-war campaigning in its target seats, can deprive the Conservatives of their incumbency bonus. If Ukip stalls and the SNP fails to break through, then maybe only the Lib Dem incumbency factor will cause Labour any problems. This would deprive Labour of only three seats it would otherwise win, so it would end up with 337 and an overall majority of 24.

Conversely, suppose the Tories end up three points ahead, and benefit from both its incumbency bonus and the decline of Ukip’s support in the key marginals. Allowing also for the Lib Dem incumbency bonus, the Tories would pick up, net, an extra 25 seats. Instead of winning 307 seats, the same as in 2010, and having to face another hung parliament, they would have 332 MPs and an overall majority of 14.

My own current guess is that both Labour and the Conservatives will fall short of outright victory. Indeed, a near dead-heat in both votes and seats is on the cards, with Labour’s geographical advantage, seen in the uniform swing calculations, offset by incumbency bonuses for the Tories and the Lib Dems, some recovery in Lib Dem votes nationally, and a modest squeeze on UKIP support in Conservative-Labour marginals. At present, I do not expect an SNP surge – though this, like my other assumptions, will change in the light of polling data closer to election day. For the moment, I reckon we are heading for something like: Labour and Conservative 294 seats each, Lib Dems 35, others 27. The post-election politics of such an outcome could be as fraught as the campaign itself. But anyone who places money on these, or any other, figures does so at their own risk.

The larger point is that uncertainties abound. I have sketched out some of the factors, and their possible impact. What is certain is that Labour and Conservative fortunes will depend at least as much on what happens to Ukip, Lib Dem and possibly SNP support as on the traditional two-way Con-Lab battle – and that uniform swing may prove a treacherous guide to anyone trying to convert national vote shares into seats.

This analysis appears in the September edition of Prospect

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

PA image