Next year’s general election will be a battle between two rival narratives – YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times suggests that the Government is edging ahead in this contest

We all know that care must be taken applying American ideas to British conditions. A prime example is the famous adage from Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign in 1992: “it’s the economy, stupid”.

Of course the economy matters here, too. In most elections it matters more than anything else. But the way it matters can vary hugely. In 1992, Britain was stuck in recession – yet the Conservatives won their fourth successive general election. Five years later, growth was strong, living standards were rising – and the Tories slumped to their worst defeat for almost a century.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

Even so, the economy determined both elections: in 1992, because voters were scared of the taxes they would have to pay under Labour; in 1997, because the Conservatives never recovered from the humiliation of the pound crashing out of Europe’s exchange rate mechanism on Black Wednesday more than four years earlier.

In short, it’s not just the numbers for growth, jobs, taxes and mortgage rates that matter, but the context that links them. In many ways, next year’s general election will be a battle between two rival narratives: “the economy’s on the mend; don’t give the keys back to the people who crashed the car” versus “the growth is too little, too late; only the rich are better off than they were in 2010”.

As George Osborne finalises this week’s Budget, YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times suggests that the Government is edging ahead in the contest between these two narratives.

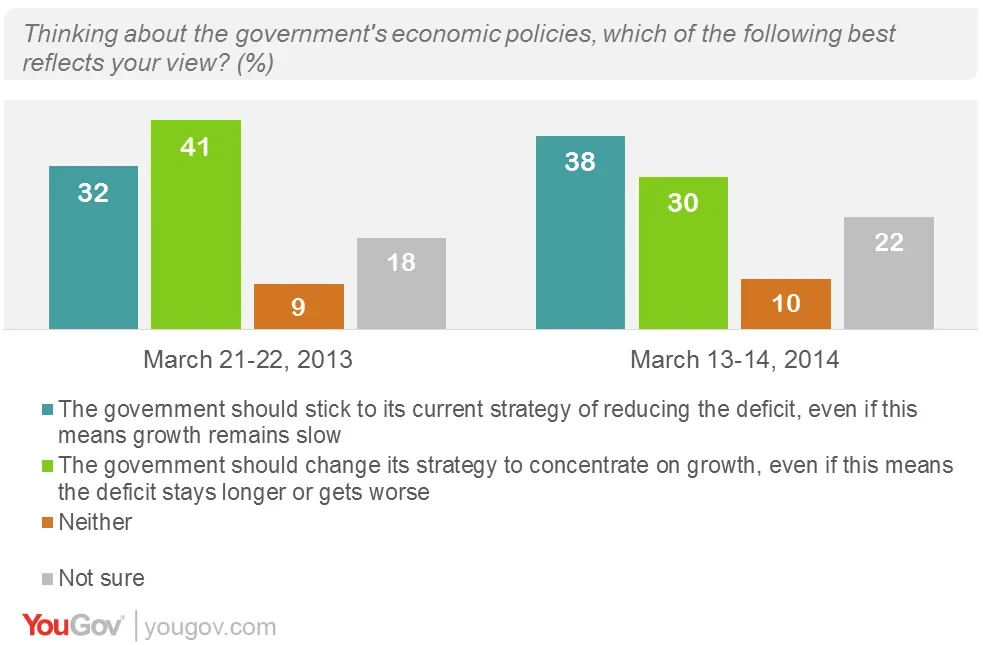

From time to time we ask people whether the Government should stick to its strategy of reducing the deficit, or concentrate more on stimulating growth. There has been a marked change since last year’s Budget. Then, voters opted by 41-32% for a switch to growth. Now, by 38-30%, they want the Government to stick to its deficit-reduction plans.

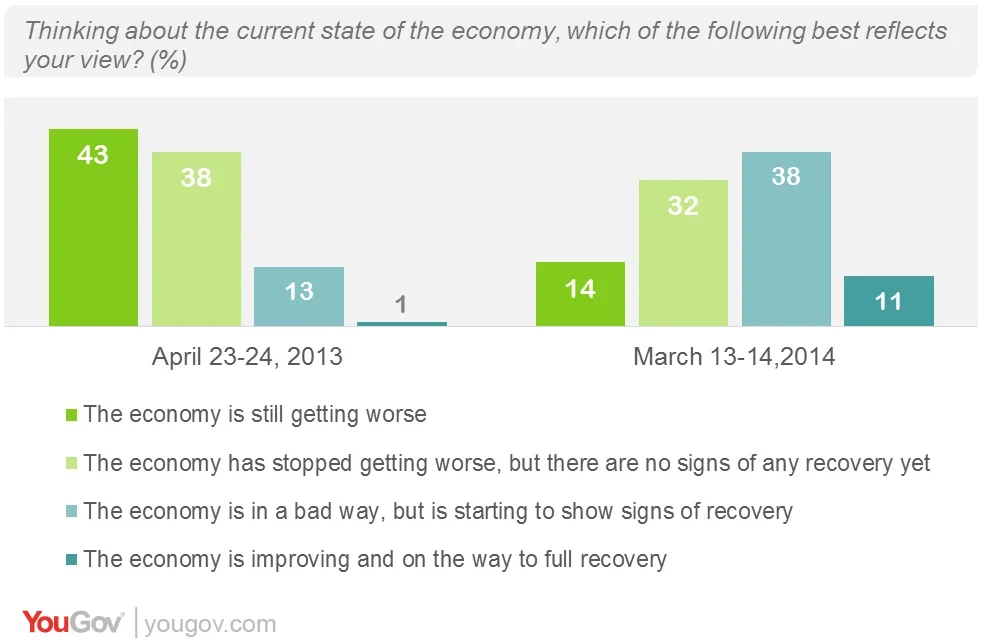

The big reason for this is that more and more people think the plan is working, and that recovery is under way. Half the public now think either the economy is “improving and on the way to recovery” (11%, compared with a mere 1% last spring) or “in a bad way, but there are signs of recovery” (38%, up from 13%). The proportion thinking the economy is either getting worse or bumping along the bottom has tumbled from 81% last spring to 46% today.

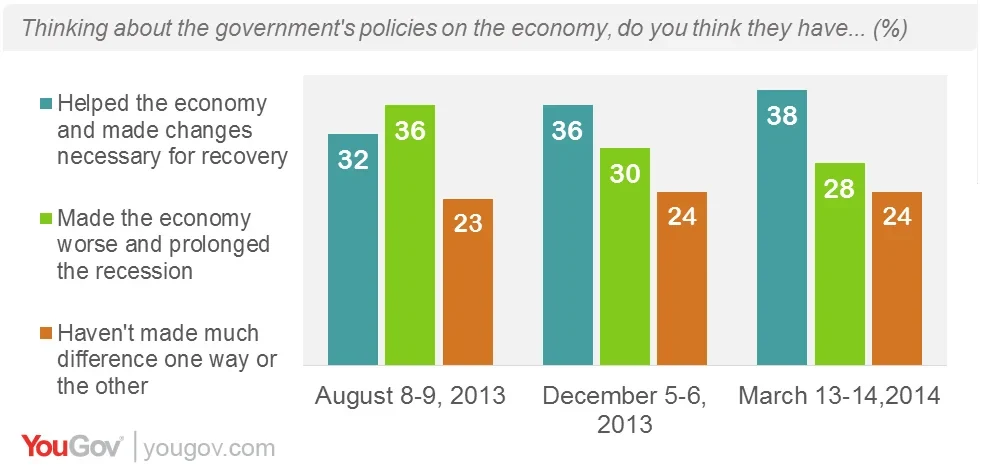

Meanwhile, Ed Miliband and Ed Balls are losing the argument that coalition policies have done more harm than good, and that Labour would do any better. Since last summer, the proportion saying “the Government’s policies have made the economy worse” has declined, gently but steadily: August 36%, December 30%, now 28%. And only 19% now think that the economy would now be doing better had Labour won the 2010 election – the lowest figure yet.

When we put the two parties head to head, Labour enjoys a four point lead over the Tories on jobs, and a five-point lead on living standards. But the Tories are ten points ahead when people are asked which of the two main parties they trust more “to make the right decisions about improving the state of the economy”.

Does this mean the Tories should now be odds-on favourite to win next year’s election? Not necessarily. They may feel encouraged by these latest poll numbers, yet Labour retains its clear, if modest, voting intention lead: 7% in the latest survey. And the Government remains vulnerable on two linked points: being seen as out-of-touch with normal people, and presiding over a recovery that has yet to translate into higher living standards for millions of people on average and below-average earnings.

It is not too late for Miliband to persuade voters that he is able to deliver higher living standards for all, not just the rich; but Cameron will hope that by this time next year, enough voters will feel better off, and sufficiently optimistic about the future, to spurn Labour’s message.

This commentary appears in the latest issue of The Sunday Times

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

Image: Getty