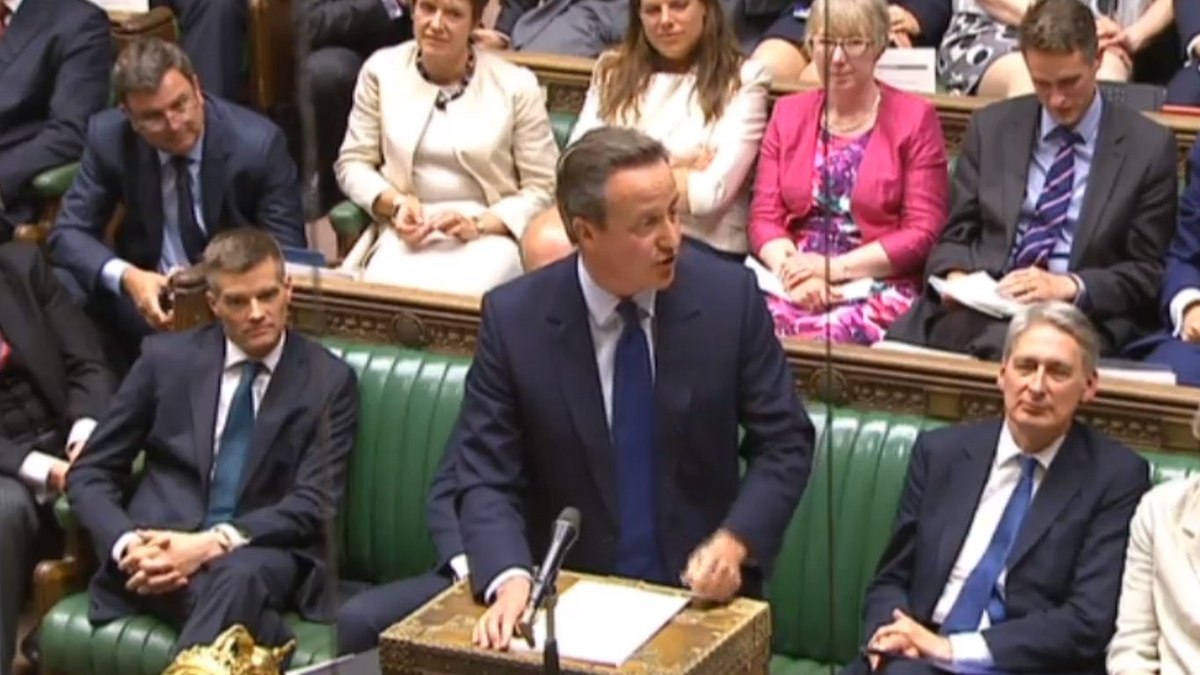

David Cameron hoped that this week’s Queen’s Speech would signal that there is purpose behind his government beyond the EU referendum and that, after all the acrimony the referendum has engendered in his party, it can still unite to carry out that purpose.

Yet the proposals outlined by the Queen have been criticised by many, including some in his own party, as tepid, marginal and unimpressive. Meanwhile, the Tory Party is continuing to tear itself apart over Europe. So is the Queen’s Speech what the Prime Minister claims it to be, a bold agenda for the remaining years of his premiership? Or does it serve to show that the wheels are coming off the Conservative government?

Initially Mr Cameron planned to hold the state opening of Parliament after he’d got the referendum out of the way. But he was persuaded that waiting until late June or early July would leave his government exposed in the meantime to the charge that his was a one-issue government, and a highly divisive issue at that. So he had the Queen get in her State coach and don her crown this week instead. Her speech was intended to show us the drive and ambition his government would be made of once politics got back to normal after 23 June.

Early on in the referendum campaign the Prime Minister took time out to articulate the broad aims of his remaining four years or so in office. Having spent his first six years in Downing Street concentrating primarily on the economy and (he hopes) settling the European question, he wanted to plant his standard of a compassionate, one-nation Conservatism committed to social reform. So he delivered a series of major speeches on such as issues as the condition of children in care, the state of our prisons and the need to do more to improve social mobility.

The Queen’s Speech was intended, among other things, to put flesh on these bones. Mr Cameron said it provided evidence of the government making ‘bold choices’. But in the eyes of many, his proposals do not seem at all bold and he has been criticised for ducking issues where he promised to be bold.

The centrepiece of his new legislative agenda is a bill to reform the way prisons work. The Prime Minister calls it the ‘biggest reform of our prison system for a century’. At its heart is a pilot scheme involving six prisons, including the biggest, Wandsworth Prison, to give much more autonomy to prison governors in how they use their budgets and what polices they pursue in their own prisons. Among other measures there is a proposal to use a new generation of satellite-tracking tags that will enable prisoners to be inmates only at weekends and to work outside on the community during the week. This, it’s hoped, will help prisoners once their sentences are completed to reintegrate in life outside and not reoffend in the high numbers they do now.

In themselves these measures have been widely welcomed by those involved in the penal system. But they have been criticised as not even trying to tackle the real problem of prisons: their chronic overcrowding. There are 30,000 more prisoners now than there were at the end of Margaret Thatcher’s period in office. Prison reformers attack politicians of all parties for tying the hands of judges and forcing them to sentence criminals to prison when they could be much better dealt with through non-custodial sentences. The result has been prisons crowded out by people who shouldn’t be there, they argue. The government’s new measures, they complain, don’t tackle the real problem.

That, in general terms, is the flavour of the criticism of much of the rest of the government’s ‘bold’ new agenda. Measures on making adoption faster, giving everyone a legal right to fast broadband, facilitating the creation of new universities and so on are all right in themselves, the critics say, but they are not going to transform the country. Defenders of the government say that is to misconceive the point of a Queen’s Speech which by its nature should be workmanlike and pragmatic, dealing with the issues that need dealing with rather than ushering in a revolution. In which case, say the nay-sayers, why call it ‘bold’?

More strident criticism has come for what has been left out of the Queen’s Speech. Eurosceptics claim they were promised a bill that would reassert Westminster sovereignty over Brussels and that they have been let down. Iain Duncan Smith, who resigned from Mr Cameron’s cabinet earlier this year, said: ‘Many Conservatives have become increasingly concerned that in the Government’s helter skelter pursuit of the referendum, they have been jettisoning or watering down key elements of their legislative programme. Now it appears the much-vaunted Sovereignty Bill, key to the argument the PM had secured a reform of the EU, has been tossed aside as well’.

David Cameron’s hope that the Queen’s Speech would provide a rallying point around which the party could reunite after the referendum is weakened by these criticisms. But the whole task has been made much more difficult anyway by the increasingly personal acrimony of the debate over Europe.

The Prime Minister had initially expressed the hope that the two sides in the party’s deep-rooted and long-standing divisions over Europe could conduct themselves in a gentlemanly way. He said: ‘We should all be big enough to have an honest and open but polite disagreement, and then come back together again afterwards’. But, at least in the view of those on the other side of the argument from him (and even some on his own side), the Prime Minister himself crossed the line of mutual respect at the outset when he hinted that his rival for the leadership of the party, Boris Johnson, had come out at the last minute for Brexit only for reasons of personal ambition. Since then, both sides have been impugning the other’s motives and personal character.

This personalising of what the Prime Minister claims he hoped would be campaign only about the issues, took a wholly new turn this week with a stinging attack on the character of Mr Johnson by the veteran europhile and former deputy prime minister, Lord Heseltine. This followed Mr Johnson’s having made comparisons between the aims of the European Union and those of Napoleon and Hitler.

Lord Heseltine said the ‘strain’ of the campaign was obviously proving too much for Mr Johnson; that he had indulged himself in ‘obscene’, ‘preposterous’ and ‘near-racist’ remarks; and added that members of the party ‘will question whether he now has the judgement’ to lead it. He said for good measure that he strongly doubted that Mr Johnson could ever become prime minister. Many saw the hand of Number Ten behind this intervention.

In turn, Mr Duncan Smith dismissed Lord Heseltine as being ‘a voice from the past’.

With five weeks still to go in the referendum campaign, many Tories fear this name-calling can only get worse. The question therefore is whether there is still any chance that Tory unity and therefore effective government can be achieved afterwards. Unless there is a decisive win for one side or the other (and this looks unlikely), the side that loses seems certain to feel aggrieved that it lost because of these personal attacks from the other side. A narrow loss for those who want to leave the EU is unlikely to see them pack their bags and acknowledge that the game is up, so a victorious Mr Cameron may discover his victory is pyrrhic. The personal acrimony may get even worse.

In this context, how relevant will the Queen’s Speech be either in reuniting the party or in forming the basis of a return to normal government? Ken Clarke has said that if David Cameron loses he will be out of Downing Street in thirty seconds. But even if he wins, will he have to draw up an entirely new Queen’s Speech?

What’s your view? Do you think the Queen’s Speech was the bold affair the Prime Minister claims it was, or not? And do you think the Tories can recover from the acrimony of name-calling in order to be able to govern effectively after 23 June?