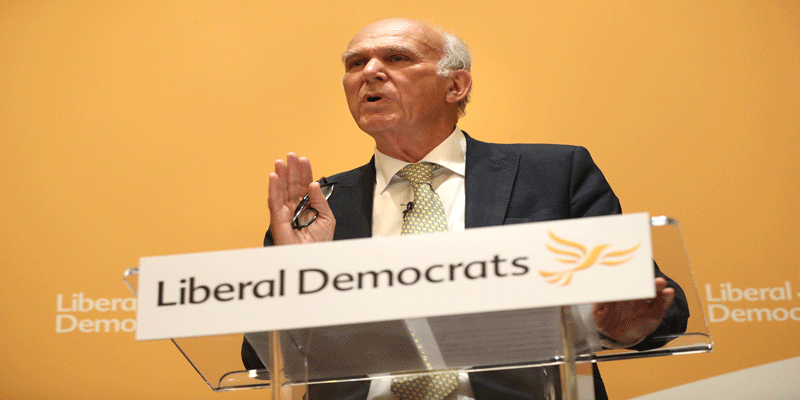

Sir Vince Cable this week became the new leader of the Liberal Democrats. Even his most avid supporters would probably not want to claim this is earth-shattering news: after all, he was unopposed.

What’s more, the relevance of his party is itself in question after a general election that seems to have returned British politics to the norm of two-party dominance. Yet Sir Vince believes the main two parties provide ‘a government that can’t govern and an opposition that can’t oppose’ and wants to put his party back ‘at the centre of political life’, not least on the issue of Brexit. Can he make his party matter again?

Politics, as we all know, is a chancy and wholly unpredictable business. Little over three months ago Sir Vince was an ex-Cabinet minister in his mid-seventies who had lost his Commons seat and was facing the prospect of having to wait another three years for a general election, the first opportunity to win it back. By then he might have concluded he was getting too old to bother. Now, just a few eventful weeks later, he has not only regained his seat (with a large majority) but has become the leader of his party, vowing to make it once again ‘a credible, effective party of national government’.

There will be plenty of people not just sceptical of this ambition but derisive of it. Since when, they will ask, has electing a seventy-four-year-old leader been the model for reviving a political party that has twice taken a battering in two years? Such an ageist attitude would not, of course, be endorsed by the writer of this piece, a mere few months younger than the new Liberal Democrat leader. But it is fair to report that even members of his own party regard Sir Vince as a caretaker. He, however, does not see it that way at all.

More serious a problem may be the party itself. Having reached a post-war peak of over sixty MPs at the 2005 election (in part the result of its resolute opposition to the Iraq war), the party kept almost all those seats at the 2010 election to hold the balance of power and become the junior members of David Cameron’s coalition government. It then paid the price. Having, in government, reversed its popular policy on university tuition fees and having become associated with an increasingly unpopular policy of ‘austerity’, the LibDems were decimated at the 2015 election, being reduced to eight MPs and to seeming irrelevance. The party continued to pay that price in this year’s snap June election, when it lost even some of those seats it had clung on to, though ending up with a net gain of four, at twelve. Only 7.4% of those who voted thought the party worthy of their backing.

This came as a blow because it was a surprising result not just to the party itself but to many commentators. The LibDems have long been the most enthusiastic pro-EU party so it was expected that a large part of the 48% of the electorate which had voted to remain in the European Union in the referendum would rally to the LibDems, not least because the party was offering a second referendum once the terms of Brexit were known and including the option of Britain changing its mind and deciding to stay in the EU after all. But this did not ultimately appeal to many Remainers, many of whom seem to have concluded that the decision on Brexit had been taken and that they must just try and make the best of it. A large group of Remainers appear to have voted Labour on the grounds that Jeremy Corbyn’s party seemed to be in favour of a softer form of Brexit than the Tories.

This makes Sir Vince’s pitch now all the more striking. He said on Thursday, as he was being crowned leader, that his party would offer an ‘exit from Brexit’. He insisted Britain needed to remain in the single market and the customs union and he repeated the call for a second referendum. The phrase ‘exit from Brexit’ clearly implies the option of remaining in the EU, albeit only after a second referendum had endorsed it.

Other politicians who were steadfast Remainers at the time of the referendum seem to believe (like many former Remain voters) that it is now too late to be talking of staying and that Britain will leave, however much they may still find that regrettable. Ken Clarke, the veteran Tory Europhile who has not changed his own views at all, is a case in point. The overwhelming Commons majority in favour of triggering Article 50 (which set the process of leaving going) persuaded him of this, he says. The argument has now shifted to whether Britain should seek a hard or a soft Brexit. As alarm at possible economic chaos at the moment of departure (March 2019) grows, there are increasing efforts to find a ‘soft’ solution, currently focused on negotiating a long transition period after leaving, in which trade could continue unhindered pending a new trade arrangement. Reports suggest the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, has persuaded even his most Eurosceptic colleagues in the Cabinet to accept this, and Sir Vince has encouraged support for Mr Hammond as ‘one of the few voices of sanity in the government’.

The trouble is that his talk of an ‘exit from Brexit’ also encourages those who smell a rat. They are already suspicious that a ‘soft’ Brexit is just code for no Brexit and believe that Sir Vince’s phrase exposes the truth of their suspicions. His espousal of a second referendum serves simply to confirm this and they regard any talk of it as a betrayal of the first. Even many of those who wish we had never voted to leave the EU fear that even calling for a second referendum, never mind holding one that reversed the initial result, would outrage the substantial part of the electorate which is both committed to Brexit and also already deeply antagonistic to what they see as an elite that wants always to call the shots. Talk of an ‘exit from Brexit’ is playing with fire, they say.

But even from the narrower perspective of the Liberal Democrats’ interest, offering an exit from Brexit may do little good. Sceptics say it did not work at the recent election and it won’t next time when the public will have got used to the idea that we are leaving. The party needs a different strategy, based on picking up a popular issue and running with it. (Just avoid tuition fees, is the advice.)

Sir Vince clearly does not want his party to speak only about Brexit. He says ‘there is a huge gap in the centre of British politics and I intend to fill it’. But there is talk of centrism elsewhere too. Chatter among disaffected centrists in both the Tory and Labour parties circles around whether a new centre party is needed. The example of Emmanuel Macron stares them in the face. In little more than a year, a largely unknown thirty-nine- year-old French politician set up a new centrist party and with it won the presidency and a huge majority in France’s parliament. Maybe the same thing could be done here. Sir Vince acknowledges this talk. He told the Financial Times: ‘We must be at the centre of this formation, whatever it happens to be… I don’t have a dogmatic view about precise structures, but I’m open for conversations.’

So what is the future for the LibDems and Sir Vince? Is he too old to be a party leader or is his experience a vital asset? Is the Liberal Democratic Party the right vehicle for centrist politics in Britain or do we need something new? Should an ‘exit from Brexit’ and a second referendum still be options on the table for the British people, or have we now settled the principle of Brexit, with only the terms of our leaving to be decided?

Let us know what you think.

Image PA