Many voters prioritise good trade relations with China over picking arguments with Beijing about human rights - but flinch at the idea of direct UK investment by the Chinese government. Voters also hold a broadly neutral view of Chinese foreign policy along with limited expectations of political change coming to China, either through domestic reform or outside pressure.

UK policy on China has seen much debate since Chancellor George Osborne opened the door last month to Chinese companies buying stakes in Britain’s nuclear power plants. The offer is initially restricted to 30% ownership of a single plant at Devon’s Hinckley Point but includes the option of expanding the policy and allowing Chinese investors to own majority stakes in future energy schemes.

Critics believe it gives too much strategic leverage to Beijing, which could limit our ability to challenge the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on issues of human rights, foreign policy and climate change. Others warn it leaves the country’s critical infrastructure vulnerable to cyber-attacks while raising safety concerns around the lax regulatory standards associated with Chinese companies.

Those in favour play down the likelihood of the CCP gaining much leverage and claim various economic and environmental benefits, such as shifting the burden of energy investment away from British taxpayers, easing our dependency on imported fossil fuel, protecting against its price fluctuations, and helping to reach national carbon reduction targets.

Trade relations v. human rights

The Hinkley announcement closely followed a high profile China visit for Osborne and London Mayor Boris Johnson in October. This was ostensibly to boost trade links but also signalled the official end to a diplomatic freeze between Beijing and London that began last year when Prime Minister David Cameron met with the Dalai Lama - the spiritual leader of Tibet and its campaign for independence - thereby putting human rights front and centre of bilateral relations.

According to research for the YouGov-Cambridge Programme, public opinion supports the return to mercantile diplomacy, with many voters favouring a more business-first approach to UK-China relations, which puts trade before promoting human rights.

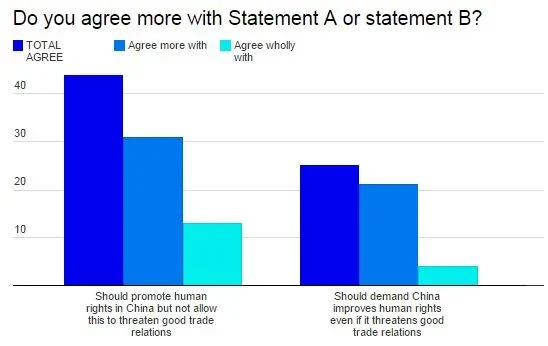

Respondents were shown two statements about UK-China relations and asked if they agreed more with either – or with both to a similar degree.

Statement A:

'The United Kingdom should promote human rights in China where possible, but we should not allow this to threaten good trade relations between the two countries'.

Statement B:

'The United Kingdom should demand that the Chinese government improve human rights in China, even if this threatens good trade relations between the two countries'.

According to these results, a plurality of the public (44%) favour the first approach – of promoting human rights where possible but not if it threatens bilateral trade.

Only 12% agreed with both statements equally and a quarter agreed wholly or more with Statement B, saying we should talk tough to Beijing on human rights even if it upsets trade.

UKIP supporters were the most vehement in favouring trade over human rights (61% for Statement A versus 17% for Statement B), followed by Conservatives (52% for Statement A versus 19% for Statement B). Labour and Lib Dem supporters still showed strong pluralities in favour of trade relations – 41% for A versus 26% for B and 42% for A versus 36% for B respectively.

Fieldwork was conducted online between 28-29 April, 2013, with a total sample of 1632 British Adults. The data have been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

Limited expectations of political reform

The British public also see limited hopes for changing how the Chinese government behaves towards its population, either from within or without.

Respondents were asked to describe how they see China’s political system today by choosing a number from 1 to 7, where 1 means ‘not at all free’ and 7 means ‘completely free’.

72% gave China a low freedom score of between 1-3 – perhaps unsurprisingly – with 9% giving a middle score of 4 and 6% choosing a high freedom score of 5-7.

We then asked respondents to say how they think China’s political system will look in 10 years’ time.

The proportion giving China a low freedom score of 1-3 fell from 72% to 47%, while 22% gave a middle score of 4 and14% predicted a high freedom score of 5-7. (NB: for the sake of reference, the 5-7 range is where a majority of British respondents - 68% - scored their own political system; see Q1 in results below)

In other words, people expect China’s political system to make a small shift towards greater freedom over the next decade – but not much.

Little faith in the power of outside influence

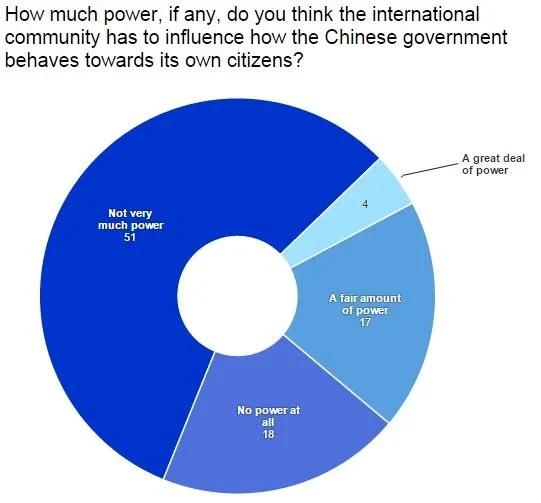

Results further show little faith on the part of British voters in the power of the international community to influence how the Chinese government behaves on matters of human rights.

When asked how much power the international community has to influence how the Chinese government behaves towards its own citizens, 69% said either not very much (51%) or no power at all (18%), versus 21% saying a fair amount (17%) or a great deal (4%) of power.

Fieldwork was conducted online between 28-29 April, 2013, with a total sample of 1632 British Adults. The data have been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

China gets a ‘free ride’ on the world stage

On the world stage, meanwhile, it looks as though China gets the benefit of non-attitudes from much of the British public.

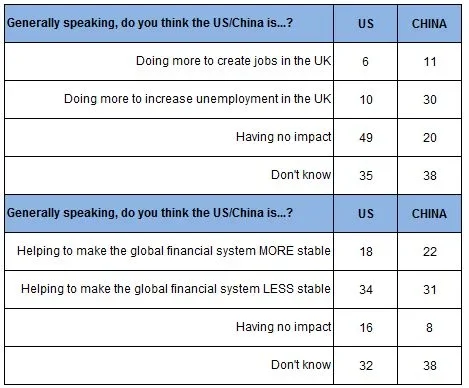

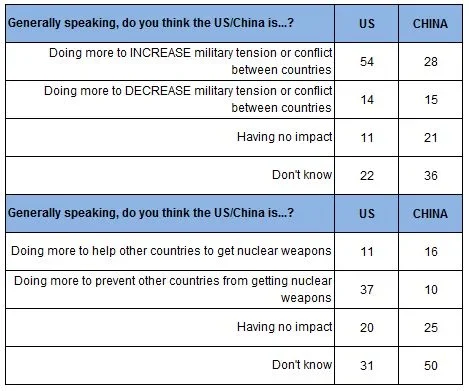

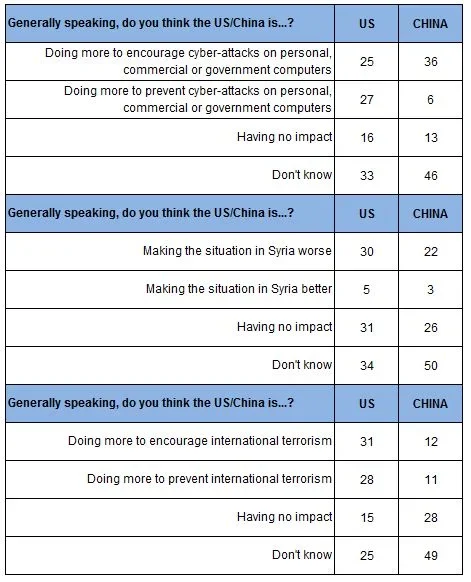

We asked respondents if they thought China was doing more to solve or worsen various international problems, including unemployment, financial stability, military tension between countries, nuclear proliferation, cyber-crime, the Syrian crisis and international terrorism.

By far the most common answer was 'Don't know’ (see the tables below). Half of respondents were unsure if China is making the Syrian situation better or worse, or doing more to prevent or encourage terrorism and nuclear proliferation. Still high proportions couldn’t say if they believed China is doing more to encourage or prevent cyber-attacks (46%), or doing more to increase or decrease military tension (36%).

For the sake of comparison, we also posed the same questions to a separate British sample – this time asking about the United States instead of China. These answers also show high responses for ‘Don’t know’, but substantially lower in most cases by comparison. They also reflected a more negative perception than of China on several counts:

● 54% said the United States is doing more to increase military tension or conflict between countries, compared with 28% saying the same for China.

● 31% said the United States was doing more to encourage international terrorism compared with 12% for China.

● 30% said the United States was making the situation worse in Syria compared with 22% saying the same for China.

In other words, China gets something of a ‘free ride’ from British public opinion in key areas of international relations, possibly owing to a lack of familiarity. As the world’s second superpower, Chinese foreign policy suffers no shortage of controversy, from support for rogue states to maritime irredentism and resistance movements in Xinjiang and Tibet. But for the British public, at least, these issues tend to feature little in mainstream news cycles.

Fieldwork was the survey on attitudes to the US was conducted online between 9-10 June, 2013, with a total sample of 1689 British Adults. Fieldwork was the survey on attitudes to China was conducted online between 6-7 May, 2013, with a total sample of 2000 British Adults. In each case, the data have been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

Clear support for investment from foreign companies - but not governments

Turning to issues behind the Hinkley Point announcement, we again posed slightly different questions to two separate samples of the Britain public, comparing attitudes to inward foreign investment in general with Chinese investment in particular.

Respondents in the first sample were asked if they thought three aspects of globalisation were good or bad for Britain, including foreign companies buying up UK companies and assets, foreign governments doing the same, and more products in the country from other parts of the world. The second sample were asked more specifically about China's companies and government doing the same, and more Chinese products in the country.

Question: The word 'globalization' is sometimes used to describe the movement of people, companies, goods, services and culture around the world. To what extent, if at all, do you think the following processes have been good or bad for your country as a whole? (question wording in second sample highlighted red)

[Foreign/Chinese] companies investing in your country, buying companies, property, land or shares in companies”

[Foreign governments/The Chinese Government] investing in your country, buying companies, property, land or shares in companies

More products in your country from [other parts of the world/China]

As results show, the public have a generally positive view of foreign companies buying into the UK economy, with 42% saying it's ‘good’ for Britain versus 23% saying ‘bad’, although it's worth noting these answers reflect significant social and regional divides: nearly half of middle class or ABC1 voters have a positive view (47%) compared with 34% of working class or C2DE voters; a similar 48% of respondents in London say it's been good versus 39% of those in the North.

It also looks like ostensibly positive news for Osborne’s announcement at Hinkley. Asking about ‘Chinese’ companies’ instead of ‘foreign companies’ makes a dent in public support, from 42% down to 35% saying it’s good for the country. But it still reflects a plurality compared with 26% calling it bad.

However, the public might be more opposed to the policy than they realise.

As the two minority shareholders in the Hinkley project, China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) and China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN) are both state-owned companies from a mixed economy, where big business remains closely aligned with national strategy and Party cadres.

In both samples, respondents are much less comfortable with the idea of other governments investing in the country and buying up parts of the economy – and even less so with the Chinese government specifically (with only 26% and 23% calling these ‘good’ for the country respectively).

Unsurprisingly, the nature of capitalism ‘with Chinese characteristics’ is not readily subject to the national debate, but it looks like the public might reflect a clearer sense of disapproval to Hinkley-type headlines and the evolving economics of UK-China relations if these referred to China’s State Council as much as its companies.

The same results suggest Chinese products have failed as yet to capture the hearts of British consumers. 33% described more products in Britain from other parts of the world as ‘good’ for Britain versus 28% calling it ‘bad’.

The effect of specifying these as Chinese products in the second sample caused a notable drop in positive answers, with only 19% calling it good versus 41% saying bad.

So ‘made in China’ may have become a ubiquitous part of the British high street. But ‘made by China’ still looks to have a serious image problem.

GB attitudes to Chinese political reform/ trade v. human rights

GB attitudes to China's role in the world