A fourth wild card is adding to the drama of the coming general election: the Greens are closing in on the Lib Dems and fourth place in the popular vote

Gradually, while Ukip has been commanding headlines, and the prospects of the Liberal Democrats and Scottish National Party cause political number-crunchers to scratch their heads, the Greens have been gaining ground. As recently as six months ago, their average rating in YouGov polls was just 2%. It is now 5% and they are closing in on the Lib Dems and fourth place in the popular vote – the position they did achieve in the European Parliament elections in May.

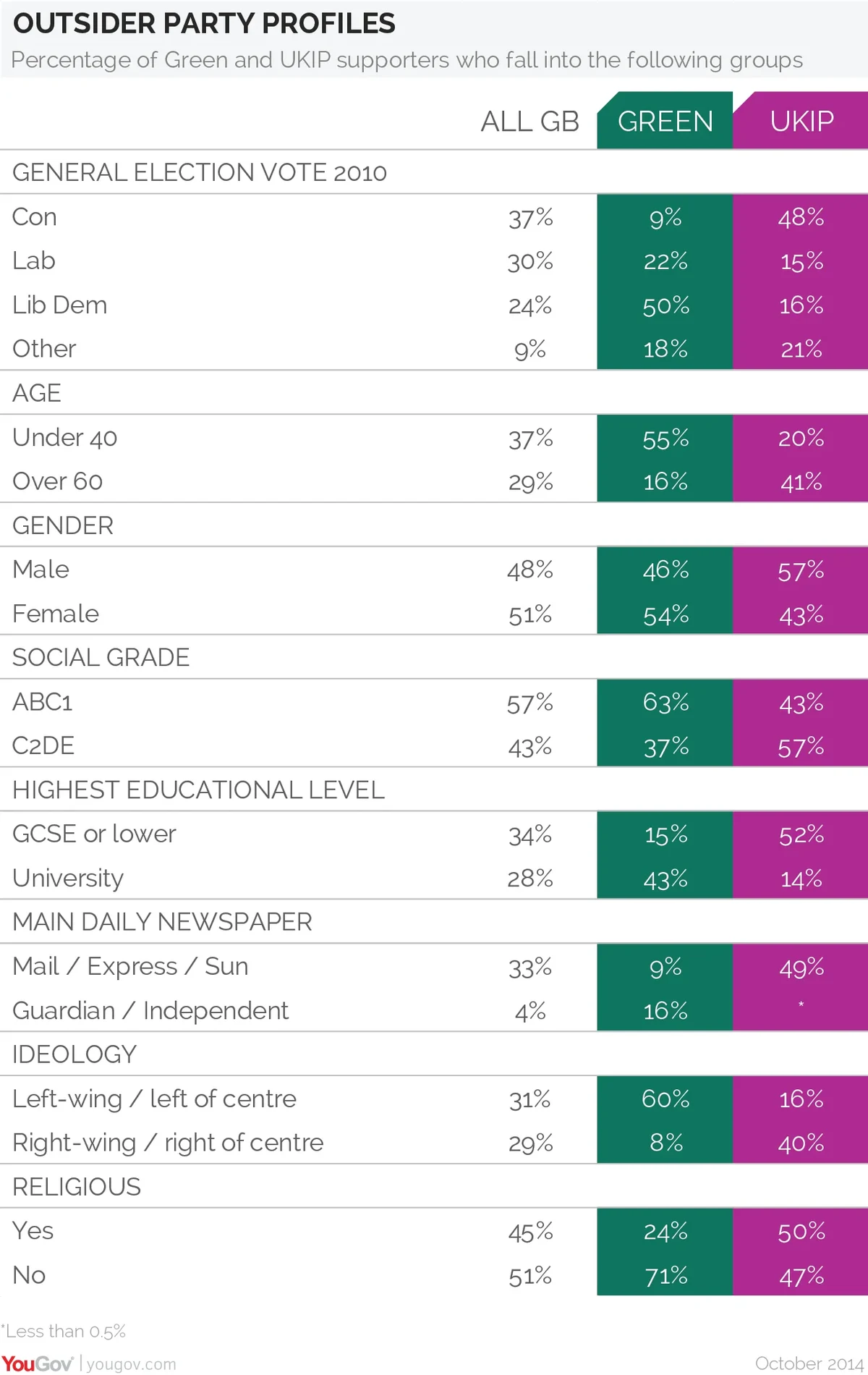

In any single survey, there are too few Greens to assess reliably what is happening. In order to make sense of the party’s advance, I have combined the results of YouGov surveys conducted during the first three weeks of October. Our total sample is 26,724, of whom 1,314 said they would vote Green and 3,401 Ukip. The table below shows how the two outsider parties compare with each other, and with the electorate as a whole.

In many ways the Greens and Ukip are mirror images of each other. Half of Ukip’s supporters are ex-Tory voters, while the Greens attracted half of their vote from the Lib Dems. Green voters are younger, more female, better-educated and more middle-class than the average – whereas Ukip voters are older, more male, more working class and far less likely to have a university degree. Ukip voters veer to the Right in ideology and choice of newspaper, while Greens veer to Left. (In fact, the Greens are more ideological: 60% of them say they a left-of-centre, while just 40% of Ukip voters place themselves on the Right.) On religion – and make of this what you will: their different age profile explains only part of the difference – Ukip voters roughly match Britain as a whole in dividing evenly on whether or not they are religious, whereas Green voters are significantly more likely to be atheists.

Taken together, what seems to be emerging is a two-headed protest vote. In the past, the Lib Dems largely monopolised the anti-big-battalion vote in by-elections – winning middle-class support to beat the Tories in the shires and suburbs, and working-class votes to challenge Labour in inner-city seats.

Those days are long past. British politics has fractured in two ways. The most obvious is that the Lib Dems are no longer an insurgent party, able to attract support when one or both of the two big parties stumble. Moreover, there has also been a long-term decline in some of the forces that used to give British politics its shape and stability. Social class and political ideology matter far less than they used to. Our political loyalties and attitudes are more varied, and so are the sources and expression of protest. Ukip and the Greens are both beneficiaries of this new political reality – as, arguably, is the SNP as it gears up to invade Labour’s heartland in Scotland next May. They all draw on different versions of our current discontents and all offer different remedies.

At this point, I should like to be able to say where this is all heading. I’m afraid I can’t. Our First Past The Post (FPTP) system for electing MPs is designed for two-party politics. This was fine when (a) the dominant argument was between capitalism and socialism and (b) all our elections were FPTP, and minor parties were kept at bay. Now we have an array of arguments – about tax, spend, Europe, immigration, identity, liberty, security, climate change and so on – and also a variety of election systems. Ukip wants us out of the European Union, but it can thank European Parliament elections, with their proportional allocation of seats, for propelling it to prominence. The same system has helped the Greens and, briefly, the British National Party.

In the short run, Ukip and Green MPs will still be thin on the ground after next May’s general election (though the SNP could break through in Scotland, where it has traditionally struggled in Westminster, as distinct from Holyrood, elections). But they could still affect the result indirectly – Ukip depriving the Tories of votes in Conservative-Labour marginals, and the Greens making it even harder for Lib Dem MPs to hold their seats against Labour or Conservative challengers.

However, looking further ahead, if Ukip and Greens maintain momentum through the next Parliament, I can see the 2020 general election leading to a far more multi-party House of Commons. This could happen if Ukip establishes itself next year as the clear second-place challenger to Labour in much of the North, as well as to the Tories along England’s east and south coasts, while the Greens build up support in university seats where they have started to put down roots. Then, in 2020, there could be dozens of seats in which the ‘wasted vote’ argument for sticking to the two big parties won’t apply, and tactical voting could help Ukip and the Greens.

That said, a word of caution. Predictions of the breakup of the Labour-Conservative duopoly have been made before. They have usually come to nothing. Most prominently, the SDP promised to ‘break the mould’ of British politics thirty years ago, and dazzled briefly before disintegrating. Maybe the Greens and Ukip will go the same way. But maybe, just maybe, they won’t, for they represent real forces, and articulate real passions, that Labour and the Conservatives, and now the Lib Dems, have so far utterly failed to repel.