Cameron may be unpopular with some of his backbench MPs, but most Tory voters rate him highly

The Conservatives’ lead may not last. It is probably a short-term reaction to the party’s annual conference and the Prime Minister’s well-received speech. Even so, the fact that YouGov has put the Tories ahead for the first time in more than two-and-a-half years – and done so twice, which suggests it is real and not a sampling fluke – suggests that we face much drama and uncertainty in the run-up to next year’s general election.

However, if we look below the surface of YouGov’s latest survey for the Sunday Times, and we find evidence that both helps to explain why Labour has lost its lead for the time being, and why Ed Miliband has more reasons than David Cameron to be apprehensive about the months ahead.

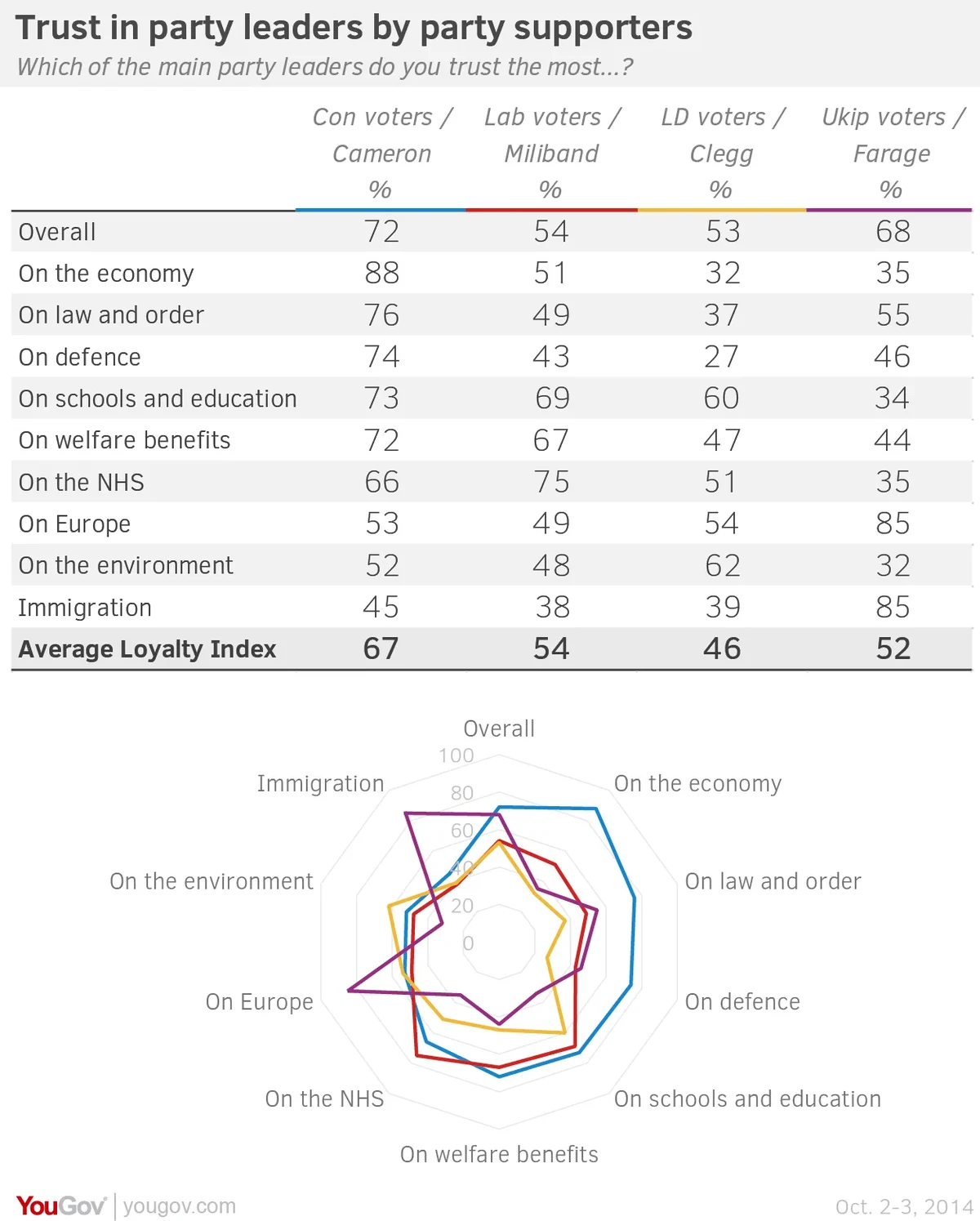

We asked people which of the four main party leaders – Cameron, Miliband, Nick Clegg or Nigel Farage – they trusted most overall, and also to take the right decisions on each of nine key issues. The topline figures for the public as a whole tell a familiar story: Cameron ahead in general and on the economy, defence and tackling crime, Miliband ahead on the NHS, Farage ahead on Europe and immigration, Clegg ahead on… nothing.

The more telling figures come when we look at the responses of the supporters of each party. How many of them trust their own leader most, and on what issues? The following table shows the results, together with an average ‘Loyalty Index’ for each leader.

Let’s consider the message for each leader in turn. Cameron wins this particular contest easily. His average score among Tory supporters – his Loyalty Index – is 67%. Miliband (54% among Labour supporters) and Farage (52% among Ukip supporters) come some way behind. Clegg, with a mere 46% among the diminished band of Lib Dem supporters, comes last.

Cameron may be unpopular with some of his backbench MPs, but most Tory voters rate him highly. He is trusted by at least 70% of those voters on six of the ten measures. Farage reaches the 70% among Ukip voters on just two measures, while Miliband does so among Labour voters on only one. Clegg does not reach 70% among Lib Dem voters on any of them. Cameron’s weakest issue is immigration. His loyalty score on this is 45%. This is because almost one in three Tory supporters trust Farage most. All in all, apart from this one, admittedly important, exposed flank, Cameron’s position is reasonably strong.

Miliband has more to worry about. There has been talk of him pursuing a core-vote strategy: seeking to hold on to a 35% vote share at next year’s election and hoping that this will be enough to make him Prime Minister. YouGov’s two latest polls put the party on 34%. Implicit in media discussions of the core-vote strategy is the assumption that these are all firm party loyalists, and that Miliband’s task is simply to mobilise them.

The trouble is, they aren’t. On five of our ten measures, fewer than half of all Labour supporters trust Miliband more than his three rivals. On a sixth, the vital matter of the economy, he only just scrapes over the half-way mark with 51%. Miliband is right to play to his, and his party’s, greatest strength: the future of the NHS. His loyalty score on this is 75%. Otherwise his ratings are weaker than he would like. If there is a case for pursuing a core-vote strategy, it is not that Labour’s base is firm, but that it is fragile and urgently needs strengthening.

Clegg’s problems are even more severe. With just 7% supporting his party, one might think the Lib Dems were down to its committed party loyalists. Not so. Most of this tiny group harbour real doubts about their party’s leader. On the vital matter of the economy, as many of them trust Cameron as trust Clegg: they both score 32%.

The figures are even worse when we look not at current Lib Dem supporters but at the far larger number who voted for Clegg’s party in 2010. The leaders they trust most are Cameron on the economy, defence and law and order, Miliband on health, education and welfare benefits, and Farage on immigration. Clegg leads only on Europe and the environment – and then with only 23% and 25% respectively.

These figures suggest that the Lib Dems will struggle to recover much ground nationally, unless they can revert to their status as an insurgent anti-establishment party, rather than as a party of insiders that fail to keep their promises. If they seek to remain a party of (coalition) government, their best hope of continuing national relevance is for their MPs to retain a personal following locally that shields them from the winds that are blowing away their support in the rest of Britain.

Farage’s figures are the most curious of all. Among Ukip voters, he enjoys extremely high scores on Europe and immigration, 85% each, but low scores on the economy (35%), health (35%) and education (34%). In terms of his public appeal, Farage looks less like a man leading a political party than a vigilante erecting a barricade. He appeals to voters who want to keep the rest of the world at bay, but have yet to decide to how Britain should be run if it did.

If next year’s election were mainly about Europe and immigration, Ukip would have a big impact, not just in terms of the seats it might win, but the way its votes might tilt the balance in Conservative-Labour marginals. But if many of Ukip’s current supporters come to think that it is less important to man the barricades than to strengthen our economy, protect our hospitals and improve our schools, then they might decide to resist Farage’s undoubted personal appeal.

PA image