At this week’s conference, Ed Miliband needs to persuade voters in both north and south of the border that he can rise to the scale of the challenges he faces

Scotland’s drama holds two big and uncomfortable lessons for Ed Miliband. The first is that the referendum campaign revealed the unpopularity of Labour’s leader in a part of Britain that his party used to dominate, and whose votes he needs if he is to become Prime Minister.

On the eve of Thursday’s vote, YouGov found that only 25% of Scots trusted him, while 67% did not. His figures were virtually the same as David Cameron’s – a shocking equality for a country which dislikes the Conservatives so much that it currently has only one Tory MP, compared with Labour’s 41. Gordon Brown’s interventions may well have helped the No campaign secure its victory last week; Miliband’s did not.

In practical terms, Miliband needs to shore up Labour’s support in Scotland between now and next year’s election. The risks and consequences of failure are great. Suppose that next spring, Scottish voters feel that London’s politicians have ratted on their pledge to act swiftly to transfer big new powers to Scotland. They might well turn to the SNP.

Only three Labour seats are vulnerable to a 5% swing to the SNP; but then comes a tipping point. An 8% swing would cost Labour 19 seats – and probably Miliband’s hopes of becoming Prime Minister.

This means that Miliband must show Scotland’s voters that his commitment to further devolution is real, and not just a shallow, panic-driven reaction in the past fortnight to YouGov’s dramatic poll in the Sunday's Times two weeks ago showing the collapse of Better Together’s lead north of the border.

But the more Miliband offers Scotland, the more he risks alienating England’s voters. The second big lesson from last week’s vote is that striking the right balance will be immensely tricky.

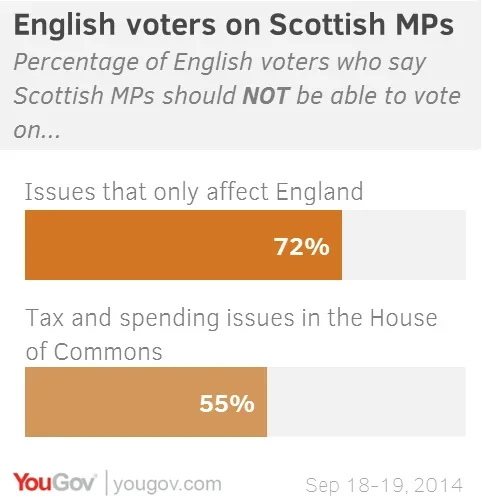

This is clear from YouGov’s latest Sunday Times survey. Not surprisingly, 72% of English voters think Scottish MPs should no longer have the vote in Parliament on issues that affect only England. Perhaps more significantly, as many as 55% also think that Scottish MPs should play no part in tax and spending decisions taken in London, even though these do affect life in Scotland. And almost two thirds of English voters want to scrap the “Barnett formula”, which ensures that Scotland receives more public spending cash per person than England from central government.

Miliband’s task would be more manageable were he to have the cushion of high personal ratings across Britain. He doesn’t. It’s not just Scottish voters who are wary of him.

Just 21% of Britons think he is doing well as party leader. He lags David Cameron by two to one (17-35%) when people are asked which party leader they trust most on the economy. A mere 9% think he is strong. By 60-20% people say he is not up to the job of Prime Minister.

Even Labour supporters remain unconvinced. Only half of them think is doing well, trust him on the economy or think he is up to being Prime Minister. In contrast, fully 90% of Conservatives think highly of Cameron.

How, then, should Miliband respond to his Scottish dilemma and his poor personal ratings? His best course would be to treat his post-referendum problems not as ones of tactical party calculation but ones of great long-term significance for the whole of the United Kingdom. If that means sacrificing Labour short-term party interest in order to achieve a lasting constitutional settlement, so be it. He might be surprised how much respect he earns.

At this week’s conference, and especially in his speech on Tuesday, Miliband needs to persuade voters in both north and south of the border that he can rise to the scale of the challenges he faces. He has his best opportunity since he became leader four years ago to rise above the daily political grind and show that he is a principled national leader.

This analysis was first published in the Sunday Times

Image: PA