Unless something dramatic happens in the next three days, a No victory is now the more likely outcome

YouGov polls have provoked a range of reactions down the years, but none caused as much panic as our survey for last weekend’s Sunday Times, showing Yes edging ahead of No. The pound fell sharply on Monday, and David Cameron and Ed Miliband agreed they should head north on Wednesday rather than slug it out at Prime Minister’s Questions.

Nerves were no calmer on Thursday, when a number of hedge funds rang YouGov seeking early guidance on that night’s figures for the Times and Sun. Nothing doing: we and the journalists kept our figures secure until just before the 10pm release time. We hope to keep our final figures under equally tight wraps this coming Wednesday; so to those who hope for an early sniff – you know who you are – don’t even bother ringing us this time.

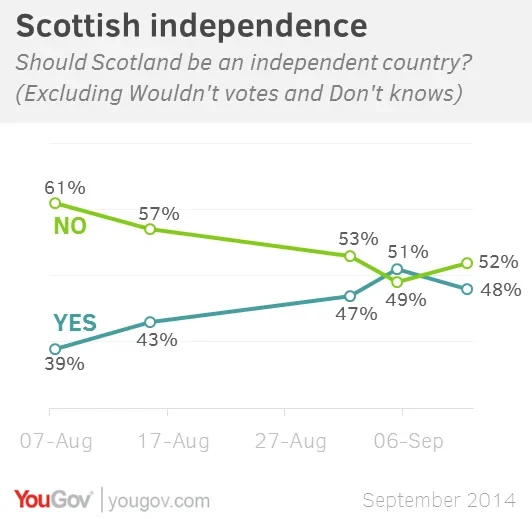

What I can tell you is that unless something dramatic happens in the next three days, a No victory is now the more likely outcome. Note the word “likely”: it’s not certain. The gap between the two sides is too narrow for that. But the momentum favouring Yes, which caused such consternation last weekend, seems to have gone into reverse.

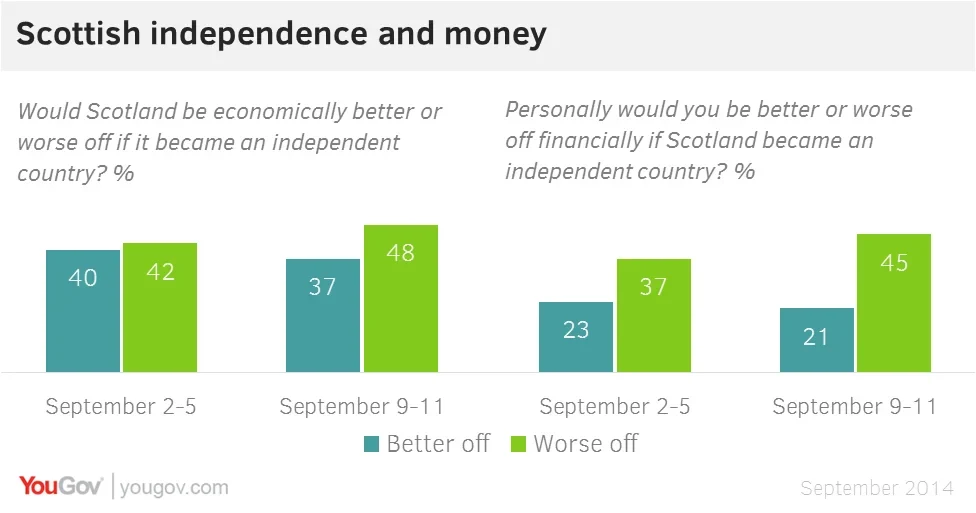

The reason? I’m afraid I must reach for a cliché; but the reason it is a cliché is that it is so often true: it’s the economy, stupid. Before the Yes surge, No held a big, steady lead because most Scots feared that independence would put jobs, investment and living standards in jeopardy. Through August, and especially in the second television debate, Alex Salmond managed to quell many of these fears.

Last week, following our shock poll, the No campaign fought back strongly, with Gordon Brown appealing to Labour voters flirting with independence. Better together was aided by retailers warning of higher prices and Scottish banks warning of moving their headquarters to London, should Yes win on Thursday. Our midweek poll caught a marked change of mood. Not only did we report a 3% swing back to No, which returned to the lead, albeit only narrowly. More significant was the six point rise in the number of Scots thinking Yes would be bad for their economy – and an eight point rise in the number fearing that their own finances would suffer.

Can Salmond reclaim the initiative after this setback? He is arguably Britain’s most skilled political campaigner. Even so, he has a monumental task on his hands.

One reason is that referendums on contested constitutional changes tend to produce a late swing to the status quo, as voters approach polling day, look over the cliff edge and some of them decide, after all, not to jump. It famously happened in Quebec in 1995.

Less remembered, but more relevant, is what happened in the first Scottish referendum in 1979. The failure of the pro-devolution campaign led to the fall of the Labour Government in London, and to Margaret Thatcher’s arrival in Downing Street. With days to go, polls showed Yes ahead with up to 60% support. Yet in the final week, its lead collapsed.

I don’t expect such a dramatic shift this time. But for Salmond to overcome both economic pessimism and the last-minute comfort of the status quo, would be a great achievement.

That said, I must own up to my fallibility. I did not predict the Yes surge. It caught me, like others, by surprise. So might the events of the final few days. Any reader or hedge fund manager who bets on my prediction should beware: you do so entirely at your own risk.

The above commentary appears in the current issue of the Sunday Times.

PS: The don’t know show

There has been much discussion about the true number of ‘don’t knows’. Recent online surveys (including YouGov for the Times and Sun and ICM for the Sunday Telegraph) have put them at 6-9%. This compares with 18% in a separate ICM telephone poll last week for the Guardian and 23% in a face-to-face poll by TNS. What explains the difference?

There are five kinds of ‘don’t know’; the trouble is, we can’t be certain how many people belong to each group.

1. People who, through circumstance, culture, language or lack of interest, seldom, if ever, vote or answer opinion polls. They are completely hidden from view, but their views, or lack of them, make no difference to the outcome of any election or referendum.

2. People who seldom, if ever, vote, and don’t join online panels such as YouGov’s, but will talk to telephone or face-to-face pollsters. In practice, they have little effect on who wins any election or referendum.

3. People who are willing to join online panels but won’t talk to pollsters who ring them up, knock on their door or stop them in the street. They are happy to give their views anonymously, but not to a stranger. (This group includes both ‘don’t knows’ and people who do have clear views and are willing to express them online.)

4. People who are willing to give their views both online and to a stranger, but react in different ways. A telephone or face-to-face poll may catch them at a moment when their minds are on other things. They may say ‘don’t know’ with complete honesty to a question put to them out of the blue. When they complete an online survey, they do so at a time of their choosing. If they face a question to which they need to give some thought, they can pause and think about it, and then give their answer. They are under no pressure to respond immediately.

5. Other people will say what they truly think online but don’t want to offend strangers. Political scientists have a clumsy term for the phenomenon of people who seek to avoid offence to telephone or face-to-face polling fieldworkers: social satisficing. It’s possible that some of the recent TNS and ICM/Guardian “don’t knows” are people who know perfectly well how they will vote, but would rather avoid taking sides on such a divisive issue as independence when asked their views by someone they have never met.

There is yet another group that must be acknowledged: people with clear views and definite voting intentions who insist on the secrecy of the ballot and never talk to pollsters, whether online, by telephone or face-to-face. If this group tilts strongly one way or another, it can make a mockery of all polling results.

In the final analysis, all pollsters assemble the best sample they can and seek to extrapolate as accurately as possible from the people they reach to the voting population as a whole. It is not, and never will be, an exact science. We all rely on our judgement. And in a close race, quite separate from the factors listed above, we always risk being caught out by random sampling fluctuations: none of us can repeal the laws of probability. That is why our final survey, for Thursday’s Sun and Times, will have a much larger sample than normal. This reduces the risk of random error.

Each of us will know on Friday whether or not our judgements have been vindicated.

Image: PA