Neither David Cameron nor Ed Miliband can draw great comfort from the European Parliament elections. UKIP’s victory holds lessons for both. What are they? Let us take them in turn.

LESSONS FOR CAMERON

Meet the Cukips. They are the voters who have triggered last week’s political earthquake. They voted Conservative in 2010, but switched to Ukip for the European Parliament election. There are more than two million of them – 15% of all those who turned out to vote on Thursday and half of all UKIP voters. More than any other single group, they will decide whether David Cameron wins or loses next May’s general election.

In YouGov’s final pre-election poll, we identified 627 Cukips; another 923 people, equivalent to around three million voters, stayed loyal to the Tories. Not surprisingly, Europe and immigration are the two big dividing issues. Indeed, so many anti-EU voters have switched to UKIP that the remaining Tory loyalists divide 49-33% in favour of keeping Britain’s links with Brussels.

However, a more fundamental dividing line separates the two groups. Two-thirds of loyalists are optimistic about the future. 67% of them are “confident that my family will have the opportunities to prosper in the years ahead”. In contrst, most Cukips are pessimists.

This pessimism is rooted in a strong feeling that Britain has taken a series of wrong turns. Unlike Tory loyalists, most Cukips oppose gay marriage, speed cameras and the ban on teachers smacking children – all reforms that Parliament has passed off its own bat, without being forced to do so by the EU.

Partly this reflects the profile of Cukip voters. Only 16% of them are under 40, compared with 32% of loyalists and 35% of the electorate generally. UKIP is easily the first choice of men over 40 – but comes only fourth among women under 40, some way behind Labour, and narrowly behind the Conservatives and the Greens.

Overall, 49% of Ukip’s voters are Cukips; 15% voted Labour in 2010, while 14% Liberal Democrat. These groups all outnumber the 7% who voted Ukip. The remaining 15% voted for a minor party or did not vote at all.

Although Cukips veer to the right on issues to do with culture and national identity, they stand well to the Left in terms of conventional ideology. Most think the privatisation of such utilities has been bad for Britain; and they want our railways restored to public ownership. Their views are far closer to those of Labour voters than Tory loyalists, who divide evenly on both issues.

That said, many Cukips intend returning to the Tories at next year’s general election. But will enough of them do so to give Cameron victory? Overall, 54% of Cukips say they would vote Conservative in a general election, while 42% would stick with Ukip. That news is not good enough for Cameron. He needs to win back more Cukips.

That is certainly possible. When we asked people how they would vote if they lived in a Tory-Labour marginal, Cukips divided 68% Conservative, 27% Ukip. The figures are similar (70-20%) for Tory-Lib Dem marginals.

Those figures show that a well-designed Conservative campaign to win back the Cukips could be successful, especially in the constituencies that will decide next year’s election. The conundrum facing the Prime Minister is how to frame such a campaign. If he moves to the Right on Europe and immigration, he risks losing more moderate voters.

Our poll suggests that Cameron best option to link economic recovery to a broader story about making life better in the decades ahead. More than fretting about the precise way to talk about Europe and immigration, Cameron needs to be the sunshine leader, and dispel the pessimism that has driven so many Tories into the arms of Nigel Farage.

LESSONS FOR MILIBAND

Ed Miliband’s central problem is easy to state but hard to solve. It is that too few voters regard him as a plausible Prime Minister. Most people think he looks and sounds weird and would be out of his depth. Few voters think his party was right to prefer him as its leader to his brother, David. And a clear majority still think that the long years of recession were largely Labour’s fault.

It used to be said the elections are lost by governments rather than won by oppositions. This is less true nowadays. Voters unhappy with the governing party (or parties) have plenty of choice. The opposition must to more than bash the Prime Minister. They must give wavering voters a reason to vote for them rather than, say, Ukip or the Greens or Welsh or Scottish nationalists.

That is why Miliband needs to sell Labour and himself, not just rage against the coalition. YouGov’s latest poll for the Sunday Times shows that his sales pitch is not working. Only 24% think he is doing well as party leader. Last autumn his rating climbed from a disastrous 20% to a merely bad 30%. This month it has tumbled back towards catastrophe.

He has also lost one slight advantage that could have cheered him. He used to enjoy a narrow lead when YouGov forced respondents to choose between a Labour government led by Miliband and a Conservative government led by David Cameron. Now the Conservatives are four points ahead. One reason is that Ukip voters prefer them over Labour by two-to-one.

This makes Labour’s overall one point lead in voting intention looks vulnerable to any Tory campaign to win back the votes it has lost to Ukip. Miliband needs to add to his party’s support – and in the final year of a parliament when oppositions normally slip back.

A Labour recovery is certainly possible: the Tories are vulnerable to the charges that they are out of touch with most voters, and have presided over falling living standards. But Miliband needs to exorcise three ghosts.

The first is the memory of his battle with his brother. Those who take sides prefer David to him by four-to-one. Labour voters are slightly more supportive – but even then only 28% reckon Ed was the right choice, while 40% believe David would do better.

On its own, that need not be fatal. But our next two findings suggest that behind those figures lurk a second, more threatening, ghost. By margins of more than two-to-one, voters think Ed ‘looks and sounds a bit weird’ (agree 56%, disagree 26%) and ‘as Prime Minister, he would be out of his depth (55-25%). Worryingly large minorities of Labour supporters share those concerns – 41% and 26% respectively.

Other results bring a bit more comfort. By three-to-two, voters see Miliband as ‘a decent man with strong moral principles’; and only one in three shares the view, advanced by leading Conservatives, that if he became Prime Minister, he would revive the ‘left-wing policies from the past that did so much damage’.

Against that, Miliband should be concerned that only one in three think he ‘is on my side and understands the concerns of people like me’. One of Labour’s big themes is that it is ‘on your side’ – unlike those remote and stuck-up Tories. Yet while most people share the criticism of the Conservatives that they are out of touch, they don’t currently buy the corollary, that Miliband is in touch.

The third ghost is the most threatening. Only 29% acquit Labour of responsibility for the recession from which Britain is now beginning to emerge. 61% think it bears at least some of the blame; and most of these think the party has failed to learn from its mistakes.

What, then, must Miliband do? Two big objectives stand out. He needs to tell a big, persuasive story about Labour’s plans to make 21st century capitalism build not just a fairer Britain (he is ahead on that) but also a more dynamic and prosperous Britain. But more than that, he needs to sound and look like a Prime Minister in waiting.

When a prominent Labour MP, Arthur Greenwood, rose to speak in Parliament on the eve of the Second World War, one Tory MP shouted out: ‘Speak for England, Arthur’. Every time Ed Miliband speaks at Prime Minister’s Questions, or gives an interview, a voice inside his head should tell him to avoid debating tricks and party point-scoring, and, instead, ‘Speak for Britain, Ed’.

AND FINALLY

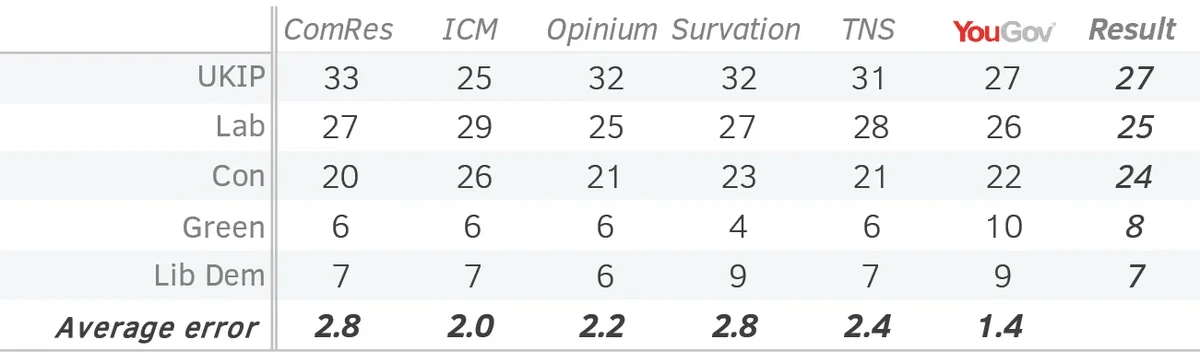

After each election, YouGov compares the final figures of each polling company with the result. Full details of YouGov past performance can be found here. Below are the figures for last week’s European Parliament elections. They speak for themselves.

The analysis of Cukip voters appeared in The Times on May 24; the analysis of Labour’s prospects appeared in the Sunday Times on May 25.