It’s not nearly enough for a party to embrace popular causes. To win votes, its policies must pass four tests. The latest YouGov/Sunday Times poll suggests that Labour’s 50p tax policy fails three of them – and might, in time, fail the fourth.

It should have been a sure-fire hit for Ed Balls. His promise to raise the top rate of income tax back to 50p, which he announced last weekend, seemed to tick a number of boxes. Polls showed that voters liked it. By raising extra money, it would make Labour’s plan to eliminate the government deficit more credible. And it would reinforce the message that, by opposing Labour on this issue, the Conservatives were on the side of the rich.

The shock, then, will have been all the greater when, late last Tuesday night, Tom Newton Dunn, the Sun’s political editor, tweeted the damning result of a new YouGov poll conducted after Balls’s speech: ‘Eds Mili and Balls sink to new low on who to trust on the economy: 24% v Cam and Osbo on 39%’. Our voting intention figures told a similar story: the immediate impact of Labour’s promise was to haflits lead from 6% to 3%.

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

These initial shifts in opinion might not last: as the news agenda changes, so will the factors that influence the daily fluctuations in party support. Labour’s real problem is that its leading lights seem to have misunderstood the way public opinion works. If they make the same error on other issues, their hopes of returning to power next year may well be dashed.

They should have known better. History offers plenty of examples of the dangers of interpreting the public mood too simplistically. And should they wish to conduct a post mortem on what went wrong this time, the latest YouGov/ Sunday Times poll contains some telling evidence.

History first. In June 1975, Britain’s first nationwide referendum produced a two-to-one majority for staying in the Common Market (as the EU was then called). Just nine months earlier, polls had recorded a clear lead for leaving, and we looked like heading for the exit. But as people started to face the consequences of withdrawal, they decided that they did not want to take the risk.

Much the same happened eight years later. In the 1983 general election, Labour promised to pull out of the Common Market if it returned to office, buoyed by polls that showed a clear majority for withdrawal. Once again, opinion turned round. By election day, Labour, weighed down by its internal convulsions, suffered its lowest share of the vote since 1918.

Other polling data through the Eighties also showed that the public rejected two of the main tenets of the Thatcher era: privatisation, and a preference for tax cuts over higher public spending. And, indeed, when the decision as to who should govern Britain was not at stake, the Tories suffered badly, in mid-term by-elections. But in general elections, Labour’s opposition to lower taxes and privatised utilities cut no ice with floating voters. In the harsh world of election campaigns, the ‘mean but smart’ Tories trumped ‘nice but dim’ Labour.

The 1992 election showed that Labour had not learned the lesson that seemingly popular policies can actually end up costing votes. It believed that its promises to increase child benefit and state pensions, paid for by higher national insurance contributions from the better off, would help it to win. Instead, voters regarded the NI plans as a tax on aspiration, feared that the promised largesse would screw up the economy – and rewarded the Tories with the highest vote that any party has ever secured in a general election (a record that still stands).

It is not only Labour that has been fooled by a misreading the public mood. In 2000, a by-election was held in Romsey, one of the Conservatives’ safest seats. The big controversy of the time was the Sangatte refugee camp near Calais. Stories abounded of asylum seekers getting through the Channel Tunnel and ending up in England. Tory private polling found that this was the number one issue for Romsey voters, and built the party’s campaign around a commitment to tackle the problem.

The plan backfired. Voters decided it was a cynical ploy. They disliked the more welcoming stance of Sandra Gidley, the Liberal Democrat candidate, but they regarded her as more principled than her Tory rival, and chose her as their MP.

Likewise, in both 2001, under William Hague, and 2005, under Michael Howard, the Tories put forward apparently popular policies on Europe, crime and immigration – but still failed to win even 200 seats in the House of Commons, let alone the 300 they needed to return to power. Many of the voters that the Tories were seeking to attract simply got the ‘wrong’ message from the Tory campaign. Instead of saying to themselves, ‘these policies chime with my views; I’ll vote Conservative’, they concluded that the party sounded rather too stridently right-wing, and obsessed with the wrong issues, to trust with government.

This journey down memory lane shows that it’s not nearly enough for a party to embrace popular causes. To win votes, its policies must pass four tests. The latest YouGov/Sunday Times poll suggests that Labour’s 50p tax policy fails three of them – and might, in time, fail the fourth.

1. The policy must be credible. Voters must think it can be done, will do some good and have no serious side-effects.

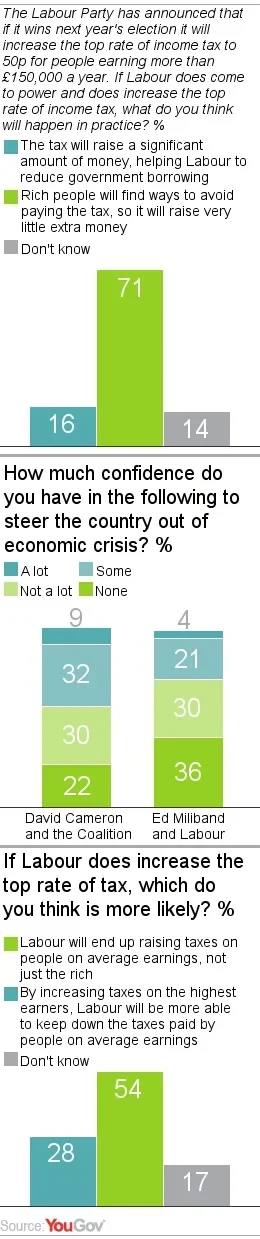

Few voters think the 50p rate will raise much money; a large majority reckons that high earners will find ways to get round it. This rather undermines Balls’s hopes that the public will see the 50p tax rate as a way to help bring down the deficit.

2. The people putting forward the policy must also be credible. Choosing which party to support is a bit like choosing a surgeon or a plumber – what matters is not just their ability to diagnose what is wrong, but their ability to put it right.

Labour continues to lag the Tories on economic competence. Just 25% say they have confidence in a Miliband-led Labour government to steer the country out of the economic crisis’, while 66% do not. Voters regard the Tories more positively (or, at any rate, less negatively): 41% have confidence, while 52% do not. And when people are asked who would make the better Chancellor, George Osborne remains well ahead of Balls.

3. The policy must not look like the thin end of a threatening wedge. Voters need to be sure that there is no hidden agenda of unpalatable policies yet to be unveiled.

Again, our poll contains bad news for Miliband and Balls. Half the public fear that ‘Labour will end up raising taxes on people on average earnings, not just the rich’; only one in three give the shadow chancellor credit for proposing a policy that will allow Labour ‘to keep down the taxes paid by people on average earnings’.

4. The policy and its advocates must be able to survive sustained examination over a period of time. A policy that sounds good at first blush might end up losing votes if its dangers start to become apparent.

The jury is still out on this. Labour has so far survived the assault on his plans from the business community. Only a minority of voters think a return to the 50p rate will deter foreign business leaders from investing in Britain. Half the public think it will have little or no effect.

However, views might change. Labour currently benefits from the fact that many business leaders – especially bankers and executives in the energy companies – are just as unpopular as politicians. Their opposition to Labour’s tax plan will have sounded to many voters like people bluffing in order to keep hold of huge salaries and undeserved bonuses.

In a general election campaign, however, reactions might change. Suppose there is a sustained campaign from the business community warning that a 50p rate could deter companies from investing in Britain and creating new jobs. Voters would not need to admire these jeremiahs, or believe that dire consequences would inevitably follow. They merely have to fear that things might get worse. Labour needs to parade business leaders whom the public respects, willing to say that such fears are groundless.

Labour still has time to put things right; but not much. Its plans to change the way its leader is elected might help, if voters come to believe that the trade unions no longer wield excessive power. But such reforms will not be nearly enough unless the party also becomes far smarter at understanding how voters think.

Image: Getty

This analysis first appeared in the Sunday Times

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here