While voters support a two-year ban on benefit payments to new immigrants from the EU, their views of the scale of the problem are exaggerated

Thirty-five years ago last Saturday, The Sun published one of the most celebrated of all newspaper headlines. James Callaghan, the Prime Minister, had returned from an international summit in the Pacific island of Guadalupe to a series of public sector strikes in Britain that gave us the ‘winter of discontent’. Callaghan deflected questions on this by deploring the more severe evils of poverty and disease faced by many other countries. His words prompted the Sun’s pithy summary: ‘Crisis, what crisis?’

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here

The same headline is appropriate today, but for the opposite reason. Far from erring on the side of complacency this time, various politicians are demanding radical remedies to a problem that is, in fact, far smaller than they suggest or voters think.

Last week, I reported that a two-year ban on benefit payments to new immigrants won our new-year knock-out policy contest. The ban – which goes far beyond the three-month ban that the Government is about to introduce – proved to be the most popular of sixteen policies we tested.

Over the past week, the idea has taken off. Boris Johnson backs it. So does Nigel Farage, who would ideally like to go even further and introduce a five-year ban. Now Iain Duncan Smith, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, says that we should be able to tell immigrants: “demonstrate that you are committed to the country, that you are resident and that you are here for a period of time and you are generally taking work and that you are contributing… It could be a year, it could be two years, then we will consider you a resident of the UK and be happy to pay you benefits.’

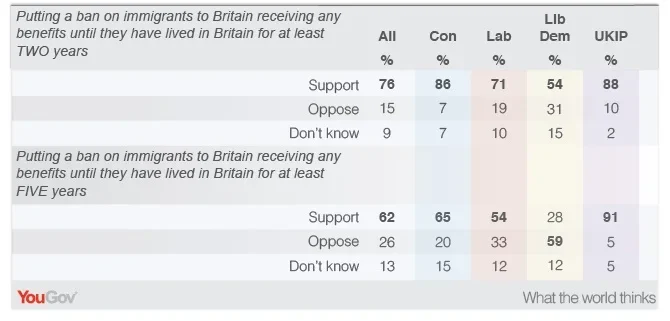

YouGov’s latest poll for the Sunday Times confirms the popularity of Duncan Smith’s proposal – and, indeed, Farage’s desire for a five year ban. We asked people whether they would support various plans to limit welfare spending. These were the responses to the proposed curbs for new immigrants:

But do voters base their views on truth or myth? As those figures show, majorities support both measures. Apart from Liberal Democrats, who support a two-year ban but not a five-year ban, strong measures to tackle welfare tourism are backed by voters across the political spectrum.

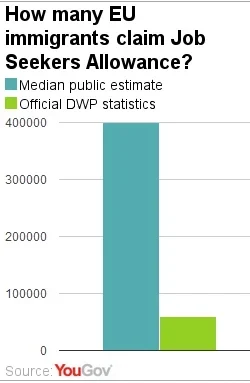

Last month YouGov conducted a survey for the think tank, Migration Matters. We asked people to say how many welfare tourists Britain is funding. We did this in two ways, to line up with the available official statistics:

Q. According to official statistics, around 2.3 million people living in Britain are immigrants from the rest of the European Union. How many of them do you think are currently claiming the main unemployment benefit, the Job seekers Allowance?

The median answer was 400,000 – almost one-fifth of residents born elsewhere in the EU. One third of all voters (and six out of ten UKIP supporters) reckon that the number is at least half a million. In contrast, the Department of Work and Pensions puts the true figure at just 60,000, a claimant rate of less than 3%.

Q. Still on the subject of immigrants and Britain’s welfare system; for anyone to claim such welfare benefits as Job Seekers Allowance, incapacity benefit or income support, they must first register for national insurance and get a national insurance number. What proportion of immigrants these days do you think claim one of these benefits within six months of obtaining a national insurance number?

This time the median answer is even higher: 23%. UKIP voters think the proportion is 46%. What does the DWP’s say? Just six per cent – less than half the rate of British-born adults of working age.

(We would have liked to test the three-month figure, to line up with the Government’s current policy, but the DWP has not supplied this data. Jonathan Portes of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research discussed this in a recent blog.

These exaggerated views of the scale of the problem do not necessarily negate the case for a two-year or five-year ban. One can want to stop welfare tourism even if few people would be affected. However, the gulf between perception and reality raises two problems.

The first is that it is unhealthy for public debate to be so ill-informed – and for politicians (of all parties) to shy away from confronting such widespread popular misconceptions. And it affects the whole of the debate about immigration debate, not just welfare tourism. As I reported in a previous blog [November 25] most people think a) immigration in recent years has been rising when it has, in truth, fallen; and b) that immigration has damaged our economy when serious economists calculate that we would be poorer without the people who have settled here.

Secondly, it is as certain as anything in politics can be that the coming three-month ban will make hardly any difference to the number of people coming to Britain. By promising a radical solution to a non-problem, ministers are riding for a fall: a policy that might well be objectively successful (if the three-month is affectively implemented) could end up deepening public disenchantment (if the flow of arrivals continues unabated because so few people are affected).

Last week, the BBC broadcast an excellent programme by Nick Robinson, called ‘The truth about immigration’. Part of its premise was that many journalists and politicians downplayed the problems caused by immigration in the past. Today, the danger is the opposite: a widespread public perception, confirmed by our latest poll, that immigrants are undermining our economy and abusing our welfare system in huge numbers.

In his Sunday Times interview, Duncan Smith talked of ‘a growing groundswell of concern about benefit tourism’. He appears not to have added that, according to his own department’s figures, this concern has little basis in fact.

Image: Getty

Want to receive Peter Kellner's commentaries by email? Subscribe here