British attitudes to the intelligence world suggest that James Bond and John le Carre hold sway for significant numbers of the public, who perceive a caricatured service that breaks the law with impunity, both at home and abroad. Our research for the YouGov-Cambridge Programme also indicates there is all to play for in the battle for public opinion on surveillance. Sympathies for the whistle-blower Edward Snowden have declined while the public looks divided on various dilemmas of security versus privacy.

Recent years have tested public trust in the intelligence services. Their work played its part in the build-up to the Iraq War ten years ago. Controversy lingers over whether they provided faulty analysis. More recently, we have had the revelations by Edward Snowden, a former contractor for the United States National Security Agency (NSA), about the surveillance work of the British and American Intelligence Services. This, of course, comes after fifty years of James Bond films – not to mention the transition from just a generation ago, when the existence of the Services was never formally acknowledged to today, when MI6 is based in one of London’s most iconic modern buildings and advertises publicly for applicants.

What, then, does the public make of what these services do today? We tested ten possible activities and asked a) whether the intelligence services ACTUALLY do them; and b) whether they SHOULD do them.

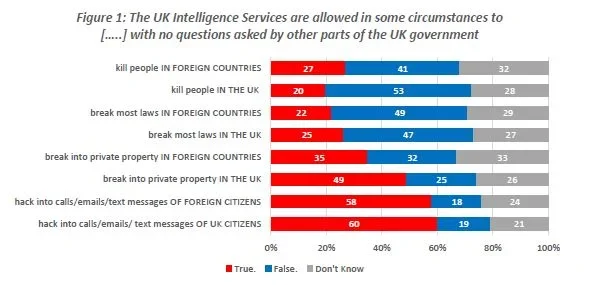

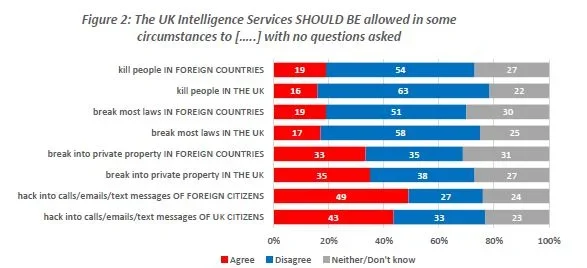

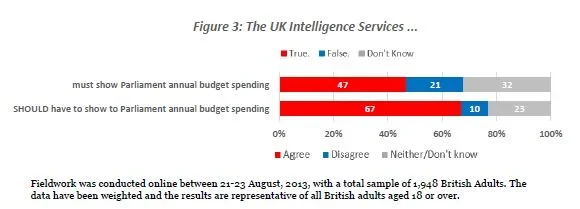

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the main findings. Apart from accounting to Parliament, all the activities we list are technically illegal. However, millions of people believe that each of these things are allowed to happen in practice.

The proportions range from 20% who think that intelligence officers ‘are allowed in some circumstances to kill people in the UK with no questions being asked by other parts of the UK government’ to 60% who think that GCHQ ‘is allowed to hack into the private phone calls, emails and text messages of UK citizens with no questions asked by other parts of the UK government’.

When we repeated the same list and asked in each case what SHOULD happen, the figures go down – though not all that much. (Once again, parliamentary scrutiny provides the exception, with the proportion saying this should be done going up, to 67% ) For example, although almost two people in three reject the notion that intelligence officers should be allowed ‘in some circumstances’ to kill people in the UK, one person in six disagrees. That means seven million adults want the intelligence services to have this power.

All to play for in the battle for public opinion on surveillance

Given recent coverage of the Snowden leaks, it is no surprise that when asking what people currently believe is allowed, the highest figures for answering ‘true’ came in response to suggestions that the Intelligence Services can hack into the private communications of UK and foreign citizens (60% and 58% respectively) with no questions asked.

But it might surprise some that in the following question, the figures for those saying these activities should be allowed remain notably high compared with other items – 43% for hacking into communications of UK citizens and 49% for foreign citizens.

These attitudes correlate to some extent with YouGov polling from the summer, where the public looks divided over the PRISM controversy, with a slightly higher figure of 46% saying they are pleased the UK security services are getting information that might help them track down criminals and terrorists, compared with 39% saying they are sorry that UK agencies might be getting round British law to undermine our right to privacy.

Similarly in a YouGov poll of British attitudes to the Snowden leaks in early June, 42% said ‘the security forces should be given more investigative powers to combat terrorism, even if this means the privacy or human rights of ordinary people suffers’. Another 29% said ‘the current balance between combatting terrorism and protecting the privacy and human rights of ordinary people is about right’, while 11% preferred to say they ‘Don’t know’. By comparison, less than a fifth (19%) said ‘more should be done to protect the privacy and human rights of ordinary people, even if this puts some limits on what the security forces can do when combatting terrorism’.

So findings suggest there is all to play for in the battle for public opinion over the right of police and security agencies to access mobile phone, email and social media records. As for the whistle-blower himself, impressions of Snowden shifted negatively between the two polls: 38% said they had a positive impression of him in June versus 25% saying they had a negative impression. In our August survey, these figures shifted to be near even, with 35% positive versus 34% negative.

Admittedly, following a summer of revelations on US and UK surveillance programmes, repeat polling in late August showed a perceptible fall in the percentage wanting more investigative powers for security forces, from 42% to 31%. But figures stayed roughly the same for those saying more should be done to protect privacy (19% in June/ 22% in August) or the current balance is about right (29% in June/ 30% in August), while the number of ‘Don’t knows’ climbed from 11% to 17%.

One reason why the public has been told more about our intelligence agencies in recent years has been to provide an alternative perspective to those provided by Bond films and spy novels. The evidence from our survey suggests that this effort has been only partially successful.