Many Britons see the Pakistani diaspora as poorly integrated, but it also has a reputation for entrepreneurship, hard work and economic independence.

With 7 million people across 140 countries, Pakistan has a large diaspora. Over 1 million of these live in the United Kingdom, making it the second largest community of overseas Pakistanis in the world after Saudi Arabia.

This community is hardly new; people from the region have been settling in the British Isles for 400 years, and long before Pakistan was founded – as it happens by a migrant to London, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who first trained as a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn before leading the new state to independence in 1947.

Even the name ‘Pakistan’ has a British story, coined by a student at Cambridge University as an acronym for its integral parts of Punjab, the Afghan Borderlands, Kashmir, Sindh and Balochistan.

So the Pakistani diaspora has deep British roots.

In the last half century, it has also become many things: the second largest ethnic minority in the United Kingdom; a rich contributor to the cultural, political and entrepreneurial life of the country; and a source of significant national insecurity, as some of the most serious terrorist threats to Britain still emanate from Pakistan and Afghanistan. The diaspora is moreover an important currency of engagement and ‘soft power’ between Britain and Pakistan itself, whose importance to UK foreign policy could hardly be overstated, from trade and Afghan reconstruction to nuclear proliferation, radical Islam and great power rivalry in Asia.

For all these reasons, YouGov is supporting a major event on Tuesday this week looking at the British Pakistani diaspora, with speakers including the Home Secretary, Theresa May, and high profile figures from the community such as Baroness Warsi; the Pakistani High Commissioner Wajid Shams-ul-Hassan; Dragon’s Den entrepreneur James Caan and Zameer Chaudrey, Chief Executive of the Bestway Group.

The event is the brainchild of Arif Anis Malik and his colleagues at the World Congress of Overseas Pakistanis (WCOP), a dynamic umbrella organisation that was recently established to help Pakistani diasporas around the world with improving relations, increasing participation and braving realities in their lands of adoption.

To support this debate, YouGov conducted a study on Britain’s attitudes to its Pakistani diaspora.

A minority of Britons say Pakistanis are integrating well, but a plurality say the opposite of their children

On the face of it, the British public appears to have a broadly negative attitude towards the issue, with only 31% overall saying that migrants from Pakistan are integrating either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ well into British society, versus 54% saying that integration is going ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ well.

This includes 66% of Conservatives and 77% of UKIP supporters saying ‘not well’, alongside a 47% plurality of Labour supporters saying the same while Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems) are near evenly split between 41% saying ‘well’ versus 40% saying ‘not well’.

This picture changes substantially, however, if we distinguish between attitudes to different generations of Pakistanis, and between respondents who do and don’t have personal contact with the community.

When asked about the children of migrants from Pakistan, and how well they are integrating into British society, the overall number saying ‘well’ versus ‘not well’ changes from 31% versus 54% to 45% versus 39%. Majorities of both Labour and Lib Dem supporters now think integration is going well and Conservatives become divided between ‘well’ versus ‘not well’. Only UKIP voters see little improvement in integration between Pakistani generations.

In other words, British concerns towards the cultural separation of Pakistanis is not wholesale across the community, and a large section of the public sees the positive integrating effect of longer settlement on the younger generations.

Figure 1: Generally speaking, how well, if at all, do you think that [migrants from Pakistan/ their children] are integrating into British society?

| Total % | Con % | Lab % | LD % | UKIP % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Migs | Chldrn | Mig | Chldrn | Mig | Chldrn | Mig | Chldrn | Mig | Chldrn | |

TOTAL | 31 | 45 | 24 | 43 | 41 | 53 | 41 | 56 | 18 | 31 |

TOTAL | 54 | 39 | 66 | 48 | 47 | 33 | 40 | 26 | 77 | 58 |

Don't know | 15 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 19 | 19 | 6 | 11 |

Older and middle class voters more optimistic about the effects of longer settlementFieldwork was conducted online between 16-17 June, 2013, with a total sample of 1705 British Adults. The data has been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

There are also interesting differences across basic demographic groups.

Older voters aged 60 and over are more likely to think that Pakistani migrants are not integrating well (65% compared with 46% of 18-24s, 49% of 25-39s and 50% of 40-59s).

But they are also more likely to think the children of these migrants are integrating well (50% compared with 38% of 18-24s, 45% of 25-39s and 44% of 40-59s).

Attitudes between different social grades are broadly similar to current Pakistani migrants but middle-class voters (ABC1) are more likely than working class voters (C2DE) to feel positive about the progress of integration for their children.

A large role for personal contact in perceptions of integration

By far the biggest differentiator in attitudes to Pakistani integration, however, is contact.

In the same survey, we asked several filter questions about whether respondents knew people from a Pakistani background among their friends and family, work colleagues or other acquaintances.

The difference between ‘contacts’ and ‘no contacts’ is stark.

51% of those with Pakistani contacts among friends or family say that Pakistani integration is going well, compared with 31% of the overall sample and 26% of those with ‘no contact’.

Similarly, 44% who know Pakistanis at work or among other acquaintances say integration is going well, versus 28% and 26% saying the same among the ‘no contacts’ respectively.

Differences between ‘contacts’ and ‘no contacts’ is further pronounced in attitudes to the next generation, with 63% of those who know Pakistanis among friends and family saying the next generation is integrating well, versus 32% saying not well, while the ‘no contacts’ are divided between 40% saying ‘well’ versus 41% saying ‘not well’.

We still see a similar effect if respondents are categorised between those who get their news from broadsheets or tabloids.

Respondents who tend to read broadsheets clearly have a more positive view overall towards Pakistani integration than those who tend to read tabloids. Among those who tend to read the Daily Telegraph, Financial Times, Guardian, Independent, or Times as first choice of newspaper, 40% say Pakistanis are integrating well versus 24% of those who tend to read ‘blue-top’ tabloids such as the Express, Daily Mail or Scottish Daily Mail. Likewise, the proportion of broadsheet readers increases to 55% who say the integration of Pakistani children is going well, versus 41% of blue-top tabloid readers.

This is perhaps unsurprising given the sensational treatment of news that can sometimes characterise the tabloid treatment of subjects such as immigration and integration.

But attitudes within each of these groups differ substantially again between those who do and don’t have contact with Pakistanis.

The proportion of broadsheet readers who think Pakistanis are integrating well falls from 40% to 29% among the ‘no contacts’ and climbs to 51% among the ‘contacts’. The proportion of blue-top readers similarly falls from 24% to 17% among the ‘no contacts’ and climbs to 33% among the ‘contacts’. Likewise, the proportion of broadsheet readers who say next-generation integration is going well jumps from 55% to 66% among ‘contacts’ but falls to 45% among ‘no contacts’.

These figures offer a mixed bag for the Pakistani diaspora.

On one hand, they tell a story of which the diaspora can be proud, namely that sections of the British public who personally know members of the Pakistani community tend to believe it is fairly or very well integrated.

But the same numbers also highlight a bigger challenge, which is that beyond the terms of personal interaction, the Pakistani community has a long way to go in fostering a broader perception of successful integration.

Pakistanis ranked lower for integration than other groups

Comparisons with other minorities examined in the same study demonstrate that Britons tend to rank Pakistanis lower down the integration hierarchy than other groups such as Eastern Europeans or those of African background.

As well as attitudes to the Pakistani community, we posed some similar questions to separate samples about people from Eastern Europe, from African countries, and from Muslim countries in general.

Attitudes are broadly negative on the integration of all groups, but African and Eastern European groups both receive higher net integration scores than Pakistanis, with 31% saying migrants from African countries are integrating well versus 46% saying ‘not well’, and 34% saying migrants from Eastern Europe are integrating well versus 54% saying ‘not well’, compared with 28% versus 57% saying the same for Pakistanis.

These results aren’t all bad news for the diaspora, however. It’s worth noting that Pakistanis receive a higher net integration score than migrants from Muslim countries in general, where 21% of respondents say the latter group is integrating well, versus 71% saying ‘not well’.

This suggests the diaspora has, to some extent, overcome ingrained British fears about the cultural challenge of Muslim integration.

There’s also a similar ‘off-spring effect’ in public attitudes to the integration of all groups referenced in the study, where the younger generation is viewed as integrating significantly better than their parents. In this case, overall attitudes to the Pakistanis show the biggest shift from negative to positive impressions of integration between the generations.

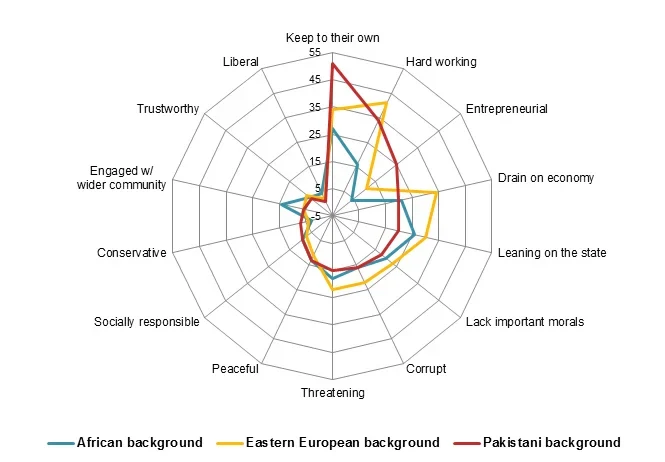

Figure 2: “Looking at the words and phrases below, which ones, if any, do you associate MOST with people from [an African/ an Eastern European/ a Pakistani] background living in Britain today? (Please select up to four or five)”

Fieldwork was conducted online between 12-13 May, 2013, with a total sample of 1748 British Adults. The data has been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

But Pakistanis are seen as playing a more positive economic role than the other groups

As part of the same study, we also asked the British public what sort of characteristics they most associate with migrants from Pakistani, African and Eastern European backgrounds. Specifically, we asked a nationally representative sample from our survey panel to select 4 to 5 options from a list of 14 words or phrases.

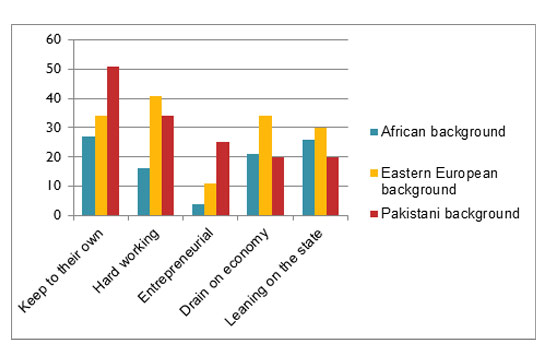

Again, there’s good news and bad. As Figure 2 shows, compared with people from an African or Eastern European background, Pakistanis are significantly more likely to be seen as keeping to their own by the wider British population.

However, the community is also seen as playing a more positive economic role overall compared with the other groups.

Pakistanis are seen as hard-working as well as more entrepreneurial and less likely to be either leaning on the state or a drain on the economy than the other groups.

Interestingly, they are also seen as less threatening in general and less corrupt than Eastern Europeans.

Figure 3: “Looking at the words and phrases below, which ones, if any, do you associate MOST with people from [an African/ an Eastern European/ a Pakistani] background living in Britain today? (Please select up to four or five)”

Fieldwork was conducted online between 12-13 May, 2013, with a total sample of 1748 British Adults. The data has been weighted and the results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

In summary, this study suggests that a majority of Britons tend to think that Pakistani migrants are not integrating well into British society. The trait most commonly associated with people from a Pakistani background is that they keep to their own, and substantially more so than either African or Eastern European communities, at least according to respondents in this study.

Personal contact is also a key differentiator in perceptions of integration. Those who know members of the community in their own lives are likely to have a positive view of integration but strong majorities with no personal link see Pakistanis as less well integrated than other minorities that have settled more recently, suggesting that a deeper history of settlement and participation has yet to translate into comparative reputational advantage in key regards.

However, these figures belie important nuances.

Pakistanis are seen as better integrated than people from Muslim countries in general, suggesting the diaspora has overcome wider fears about the cultural challenge of Muslim integration, at least to some extent. The progress of Pakistani integration is also seen as dramatically improving from one generation to the next, and to a greater extent than for those from Eastern European or African backgrounds.

Perhaps most important is the strength of the Pakistani economic story in these figures, which could offer some headlights to the WCOP and other community leaders.

Few doubt that immigration is an increasingly salient issue in British politics. As YouGov polling recently emphasised, only small numbers of Britons seem to believe that immigrants generally play a positive role in national life. Longer-running studies such as British Social Attitudes Survey further suggest that while British attitudes are far from uniform across demographic groups and categories of migrants, this is an overall trend that predates the current downturn with demands for lower immigration showing a sustained increase since at least the mid-1990s.

Notwithstanding, the issue has doubtless been amplified in recent years by the familiar effect of hard times, where blame is pointed towards migrants and minorities as an economic threat to jobs, housing and government tax receipts.

Accordingly, if the Pakistani diaspora is looking to fashion a more positive discourse of British integration, then a strong plank for this discourse could be its reputation for entrepreneurship, hard work and economic independence.

Grace Tulip, Political Intern at YouGov, contributed to the research for this study.